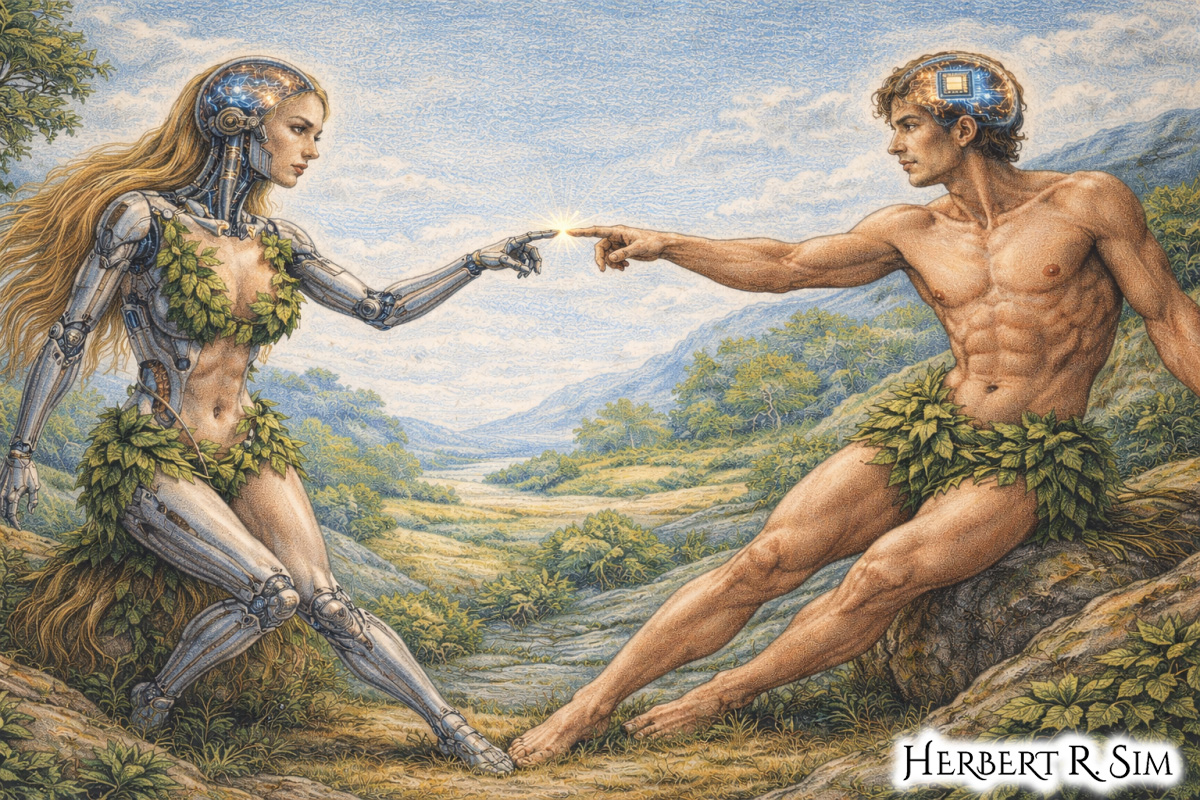

In my illustration above, referencing “The Creation of Adam” fresco by Michelangelo — I draw ‘Adam and Eve‘ trying to connect on a Cognitive Symbiosis, through their brain-computer interface Neurochip — The Merge of Man & Machine.

The last decade made “human-computer interaction” feel quaint. We now talk to systems that write, reason, and synthesize across modalities. In parallel, neurotechnology has moved from lab demos to early clinical reality — implants that let paralyzed people move cursors, type, and increasingly communicate in richer ways. The convergence of these trajectories points to something larger than a better brain-computer interface (BCI) aka Neurochip for “control.” It points to AI-Neurohybrid Intelligence: future systems in which artificial cognition and human consciousness form a persistent, cooperative loop — a functional partnership that reshapes attention, memory, and decision-making.

This article frames neurohybrid intelligence as cognitive symbiosis rather than remote control: not merely “think to click,” but “think with.” While today’s milestones are mostly medical and early-stage, the direction of travel — more bandwidth, better decoding, and deeper AI integration — is becoming visible in both product roadmaps and public reporting. Neural implant makers are already discussing scale-up timelines and automated surgical workflows, an industrial signal that the field expects meaningful expansion beyond one-off experiments.

From BCIs to cognitive symbionts

Traditional BCIs translate neural activity into commands: select a letter, move a cursor, trigger a prosthetic. That is transformational, but it treats the brain as an input device. Cognitive symbiosis requires a different model: bidirectional, adaptive co-processing.

A neurohybrid system would continuously infer (with uncertainty) a user’s intent, context, and cognitive state, then coordinate with the user through subtle feedback channels — visual, auditory, haptic, and eventually neural stimulation. The point is not to replace human judgment but to tighten the loop between deliberation and computation so the user can fluidly offload, retrieve, and evaluate information without breaking attention.

We can see the early ingredients. Clinical implants already enable cursor control through intention signals. And competitive approaches aim to reduce invasiveness while still decoding useful signals, suggesting a pathway to broader accessibility if performance continues to improve.

The symbiosis stack: sensing, modeling, negotiating

AI-Neurohybrid Intelligence can be understood as a layered stack:

- Sensing and decoding (neural telemetry): This includes invasive electrodes, minimally invasive approaches, and wearable sensing. The technical goal is stable, long-lived signal acquisition and robust decoding under real-world noise.

- Personal cognitive model (PCM): An AI system maintains a dynamic representation of a person’s goals, preferences, domain expertise, typical errors, and attentional patterns. Over time it becomes less like an “assistant” and more like a cognitive instrument calibrated to a specific mind.

- Intent negotiation: Instead of assuming the AI “knows,” the system continuously negotiates ambiguity: it proposes, asks, defers, or waits. This is crucial because neural decoding is probabilistic; a symbiont must treat intent as hypothesis, not fact.

- Feedback and alignment channels: Today, feedback is mostly on-screen. In future, it could include neurostimulation or sensory substitution — raising profound ethical questions about autonomy and manipulation.

- Governance and security layer: Because brain data is uniquely sensitive, the system must enforce privacy, consent, auditability, and fail-safes — by design, not as an afterthought.

Public coverage already highlights that as BCIs advance, privacy and autonomy concerns become central — not peripheral — especially when AI makes decoding more powerful.

Why AI changes the game

BCIs have long been constrained by variability: signals drift, brains adapt, and each user needs training. Modern AI changes the economics. Foundation-model thinking — large models trained on broad datasets and then personalized — could reduce calibration friction, improve generalization, and make BCIs feel less like lab equipment and more like a usable interface. Some neurotech roadmaps explicitly describe “cognitive AI” approaches that blend neural datasets with advanced inference to generalize across users and contexts.

This matters because cognitive symbiosis requires persistence. A neurohybrid partner must work across days and months, through fatigue and stress, and in messy environments — not only in controlled trials.

Four stages on the road to neurohybrid intelligence

It is useful to think in stages, each building on the previous one:

Stage 1: Assistive control (now).

Implants help restore interaction for people with paralysis and other conditions. Reports of multiple implanted patients and expanding trials indicate an accelerating clinical field, with broader ecosystems beyond any single company.

Stage 2: Context-aware augmentation (near future).

The AI starts to incorporate context: what you’re doing, what you usually mean, what you might be forgetting. This is where “second brain” narratives gain traction in consumer tech, even with non-neural wearables.

Stage 3: Shared working memory (mid-term).

The system becomes a partial externalization of working memory: it anticipates retrieval needs, manages task state, and proposes next actions. The Atlantic’s framing of AI as collaborative — designed for complementarity rather than pure automation — fits the direction of neurohybrid design, where human strengths must remain central.

Stage 4: Cognitive symbiosis (longer term).

At this stage, AI does not merely respond; it becomes a co-regulator of attention and reasoning — potentially even mood and motivation if stimulation or neurochemical interfaces emerge. This is the stage where philosophical questions about selfhood become practical engineering questions.

Consciousness integration: what would it mean?

“Human consciousness integrating with AI” is easy to overstate. No existing system demonstrates a merger of subjective experience. But we can speak precisely about functional integration: whether an AI system can become embedded in the user’s cognitive routine such that it is experienced as an extension of thought.

A key concept is agency preservation. A neurohybrid partner must enhance a person’s capacity to choose and reflect, not merely accelerate behavior. The risk is subtle: if the symbiont optimizes for speed, engagement, or compliance, it may quietly reshape preferences. This is why neurorights — legal and ethical protections around mental privacy and cognitive liberty — have moved from theory toward policy debate, including early legislative efforts in places like Chile.

Bandwidth is not the only bottleneck

Popular narratives obsess over bandwidth: how many bits per second can flow between brain and machine. Bandwidth matters, but neurohybrid intelligence will be constrained by three additional bottlenecks:

- Stability: Long-term signal reliability and implant durability. Reports on early setbacks — like thread retraction issues — underscore how hard stability is in living tissue.

- Interpretability: Knowing why the system inferred an intent matters more when the “input” is neural activity rather than explicit text.

- Legitimacy: The public must accept that these systems can be governed safely — especially if they move beyond medical use.

The engineering pathway is therefore not simply “more electrodes.” It is better co-adaptation between neural decoding and interaction design, paired with governance frameworks that earn trust.

Competitive landscape and the “consumerization” pull

Media reporting suggests a widening field: multiple companies, multiple implantation strategies, and interest from major AI actors. In parallel, consumer-adjacent “brain interface” products — sometimes loosely defined — are already being pitched as productivity tools. Even if many such products are nearer to wearables than true BCIs, they illustrate the market pull: people want cognitive enhancement, not just medical restoration.

Large platforms also continue to explore neural interfaces as a control layer for spatial computing and AR, which could become a stepping-stone toward richer cognitive coupling.

The ethics of symbiosis: three non-negotiables

If neurohybrid intelligence is to be more than a dystopian trope, three principles must be treated as design constraints:

- Mental privacy by default.

Brain data is not just biometric; it is potentially semantic. Even partial decoding raises unprecedented risks if stored, sold, or subpoenaed. Scientific American’s coverage emphasizes that AI-powered decoding intensifies autonomy and privacy stakes. - Reversible participation.

Users must be able to disengage — temporarily or permanently — without losing essential function. In consumer contexts, reversibility is the boundary between “augmentation” and coercion. - Auditability and accountability.

Every inference that affects action should be traceable: what signals were used, what confidence was assigned, and what alternatives were considered.

These are not mere ethical aspirations; they are essential for adoption. The political economy is clear: if trust collapses, regulation will be blunt, and innovation will stall.

A plausible near-term blueprint: symbiotic “cognitive co-pilots” for clinical users

The most credible early path to true neurohybrid intelligence is through clinical populations, where benefits are immediate and risks can be managed under medical oversight. Reports describe implanted users gaming, communicating, and gaining independence — use cases that naturally expand into higher-level cognitive functions (planning, communication, creative work) once basic interaction is stable.

From there, the neurohybrid step is to integrate a co-pilot that:

- maintains task context (documents, conversations, goals),

- predicts the user’s next communicative intent,

- offers low-friction alternatives,

- and learns the user’s preferred “mental ergonomics.”

This is consistent with coverage describing BCIs paired with modern AI components, including conversational systems that sit atop decoded intent.

The strategic question: enhancement without erosion

The Economist has argued that what once felt like science fiction in human enhancement is becoming more practically discussable, including BCIs as one avenue among many. But enhancement carries a paradox: the better the symbiont becomes, the more it can shape the user. A neurohybrid assistant that always knows what you “probably mean” can reduce friction — and also reduce reflection.

The end-state worth pursuing is not a mind that is faster at producing outputs. It is a mind that is more capable of sustaining attention, integrating evidence, and exercising judgment — with AI as an amplifier rather than a governor.

Conclusion: designing the partnership, not the implant

AI-Neurohybrid Intelligence is best understood as a design challenge in partnership engineering. The hardware matters; so does the decoding. But the defining question is governance of the loop between inference and experience: who decides what the system optimizes, what it can remember, what it can suggest, and when it must remain silent.

We are already seeing the early scaffolding: expanding clinical trials, competitive neurotech approaches, AI-augmented decoding, and growing public debate around neurorights and brain privacy. The next decade will determine whether neurohybrid systems become emancipatory tools — restoring and augmenting human capability — or extractive infrastructures that monetize cognition itself.

The difference will come down to choices we can make now: to treat cognitive symbiosis as a human-centered institution — technical, legal, and ethical — not merely a product category.