Above is my art illustration sketch of Scientists working in a lab cloning animals

————————————-

The world of gene editing and cloning has often been subjected to skepticism and sometimes indignation, especially to those who are not privy to the various developments that have occurred over the past decade.

CRISPR, a powerful genome-editing tool that took researchers by storm in 2012, continues to power various experiments and inspire relevant, new technologies. In terms of the global community, China continues to lead the way – backed by astonishing support in the shape of massive government funding and animal support to carry out large scale experiments.

For context, the Chinese were the first to harness CRISPR in monkeys and have since gone on to break new grounds in subsequent years – creating monkey models of autism and muscular dystrophy for example – in a bid to facilitate a better study of specific human diseases.

Organ transplants have also come into the picture, with a Chinese team announcing that it is highly possible to execute safe and effective organ transplants between animals and humans. This is due to the researchers’ success in creating genetically modified pigs with cells that are more compatible with our immune system.

Other applications include cloning beloved pet animals that have passed away, as well as the idea of transplanting pig corneas or insulin-making islet cells into people who signed up for clinical trials. The latter was conceived by a Korean team, reflective of an environment where the competition is heating up.

Of course, controversy isn’t always far when it comes to the topic of gene editing and cloning.

China’s editing of a human embryo’s genome in 2015 was a first – stirring scary predictions of what could happen next and severely tested the ethical boundaries as well as brought forth a worldwide debate on potential repercussions.

The act of editing a gene, let alone cloning, is to some an act against nature, of attempting to play God for selfish gains and self-preservation.

If technology could enable superior gene-editing and cloning techniques, surely someone would’ve entertained the idea of cloning your loved one who has passed away? Or perhaps, to replace a failed organ by cloning yours that would in theory – be compatible?

Before we venture into unchartered territory, let’s take a dive into the waters of gene editing and cloning.

Gene editing

As its name suggests, gene editing involves the addition, removal, or alteration of the genetic material within a specific genome, enabled by various technologies.

While there are various approaches when it comes to the gene editing process, CRISPR has been a favourite among researchers due to its speed, accuracy and efficiency as compared to other methods.

High profile case studies of gene editing have also largely used CRISPR, further enhancing its reputation and familiarity within both scientific and non-scientific circles.

In fact, China’s “brute-force” approach towards gene editing via CRISPR is unprecedented, a reference towards the large colonies of monkeys that the researchers could work with.

There were also multiple firsts for the array of CRISPR-powered research initiatives, where teams got to work with mice, rats, pigs, dogs, and rabbits.

These initiatives are meant to raise the bar in terms of producing better quality meats, disease-resistant livestock, new medical treatments as well as organs for human transplantation.

The topic of human transplantation, while sensitive, has proven to be a turning point in terms of the adoption of gene editing processes.

Scores of academic and commercial research groups in China and Germany have also attempted to use CRISPR to make up for the shortage of vital human organs, organs that could help save lives. This can be done by genetically re-engineering the hearts, kidneys and livers of pigs and render them compatible with humans for transplantation – also known as xenotransplantation.

In order to produce pigs that possess the desired traits within its organs, scientists first modify the genetic code – via the removal and insertion of specific genes – before placing the DNA-containing nuclei into eggs from the pig’s ovaries.

Once embryos are formed, they can be implanted into surrogate mothers which then give birth to piglets who exhibit the desired traits.

Apart from organs, various types of tissues from genetically engineered pigs are already being tested for human compatibility.

South Korea has been associated with transplanting pig corneas, insulin-producing pancreatic islet cells have been transplanted into people with diabetes in China, while in the US, it was announced that gene-edited pig skin was used as a temporary wound cover for a patient suffering from severe burns.

————————————-

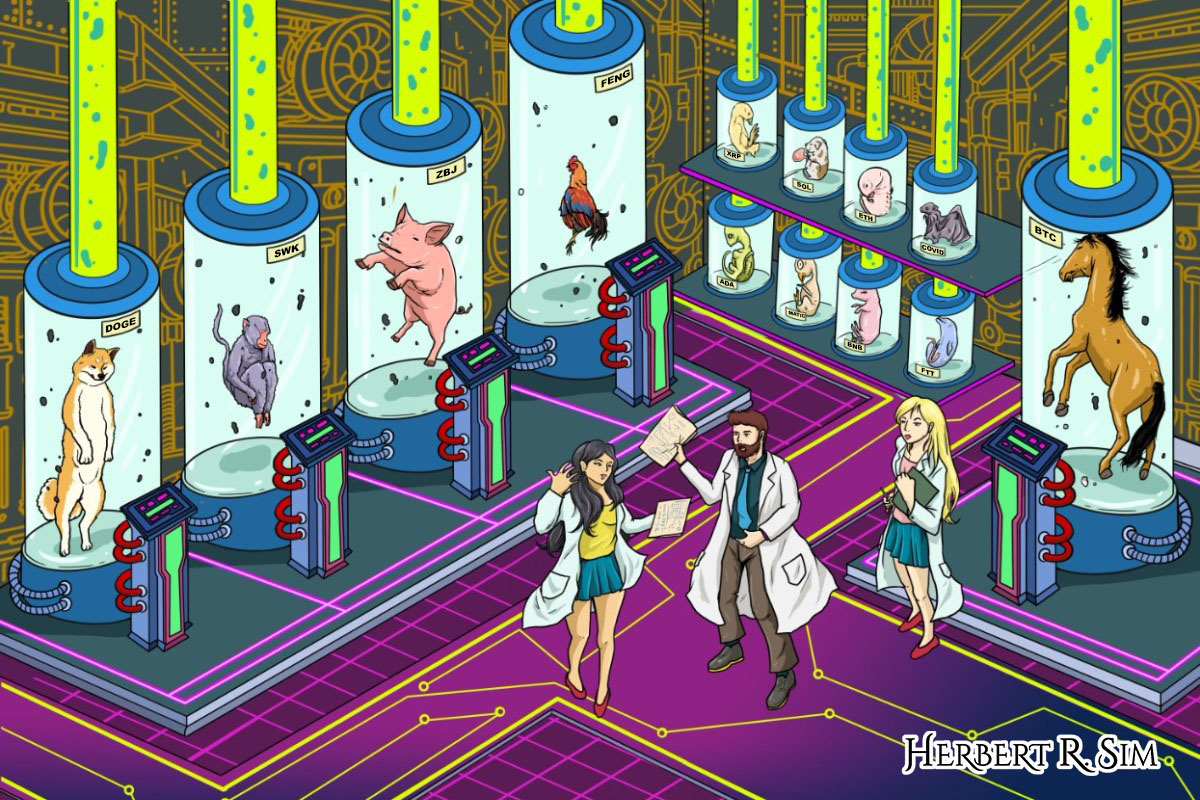

Above is my work-in-progress as I colored in the illustration.

————————————-

Cloning

Unlike the advancement of gene altering experiments, the cloning world remains one that straddles the narrative of bioethicists as well as the perceived desire to accelerate biomedical research and appeal to human needs.

Ever since the appearance of Dolly the cloned sheep in 1996, decades have passed where the cloning community has seen multiple controversies and governmental roadblocks – particularly when it concerns the cloning of humans.

In fact, animal cloning and nonhuman cloning have entered acceptance territory, with researchers facing a much more normalized environment as compared to doing the same with human beings.

Chinese scientist He Jiankui was a prominent example of facing the type of wrath that in a way, inhibited and quashed genetic experiments that had to deal with anything similar.

Essentially, he leveraged CRISPR and edited human embryos which led to the birth of two babies. The backlash was apparent and he was served with a three-year prison sentence. Apart from his eventual consequence, the edited embryos delivered a message: Why clone when you can produce an improved version of a human being?

Alas, one can see how non-human cloning experiments have largely received positive coverage and fanfare, as opposed to pro-human cloning expectations, theses, and proclamations. The latter have seen its attribution to cults such as the Raelians – declaring that their mission to clone humans was due to a religious command from aliens.

As was briefly mentioned, nonhuman cloning is seeing progress. The first monkey clones were reported in early 2018 in China, albeit with a low success rate – just six pregnancies and two live births were recorded from roughly 80 cloned embryos.

Chinese pet owners are also turning to cloning technologies in a bid to “resurrect” their beloved pets, while in Argentina, a champion polo team uses cloned horses.

Closer to our stomachs, the laboratory meat industry secured a victory when Singapore became the first nation state to approve the sale of meat cultivated from animal cells. The meat is produced in bioreactors and do not require the slaughter of an animal. Eat Just, the San Francisco-based company behind the product, will be allowed to sell its cultured chicken nuggets and this move may well trigger other countries to follow suit.

On the other hand, cloning of humans has somewhat taken a backseat, out of the spotlight and seemingly in the dark. Whether its due to public opinion, moral panics or press behaviour, or a combination of these aspects, we do understand what could transpire when gene editing and cloning experiments go unchecked.

————————————-

In the final completed art illustration, if you look closely, you can see the labels on the tanks as well.

————————————-

Of ethics and debate: Noble tweaks or selfish preservation?

Rightly so, gene editing and cloning research is still very much a work-in-progress.

What drives the narrative for people who champion cloning, isn’t just about scientific breakthrough or research enablement.

In fact, the desire to clone and the attractiveness of such methods, the shimmering potential of what could have been if genes are altered for the greater good, are often human emotions that swirl within scientific dissertations and discussions.

The grief of a family who’s just lost a loved one, the narcissism of a billionaire who wishes to have more of himself, the frantic desire of a scientist to make a mark on the community, these are just examples of how we’re simply a fine line away from making the unthinkable possible.

If we’re not talking about cloning humans, what would bioethicists think about those who wish to clone organ parts in a bid to save someone’s life? What is this boundary that we try not to cross?

We don’t know what the future would hold when it comes to developments within the gene editing and cloning circles – including how effective it is to digitize your genome and store it safely on the blockchain – which of course requires continual tweaks and solidification of blockchain technology before anything can materialize.

What we do know, is that gene-editing and its related array of activities will not cease to exist. Researchers will keep building, multiple scenarios will continue to be unearthed and adoption would eventually normalize what were once controversial and divisive topics.

Alas, the possibilities – and funding – are endless.

https://pafipemkokalimantan.org/

https://pafikabupatenpandeglang.org/

https://pafikabupatenprobolinggo.org/

https://pafikabupatenpamekasan.org/

https://idikotapontianak.org/