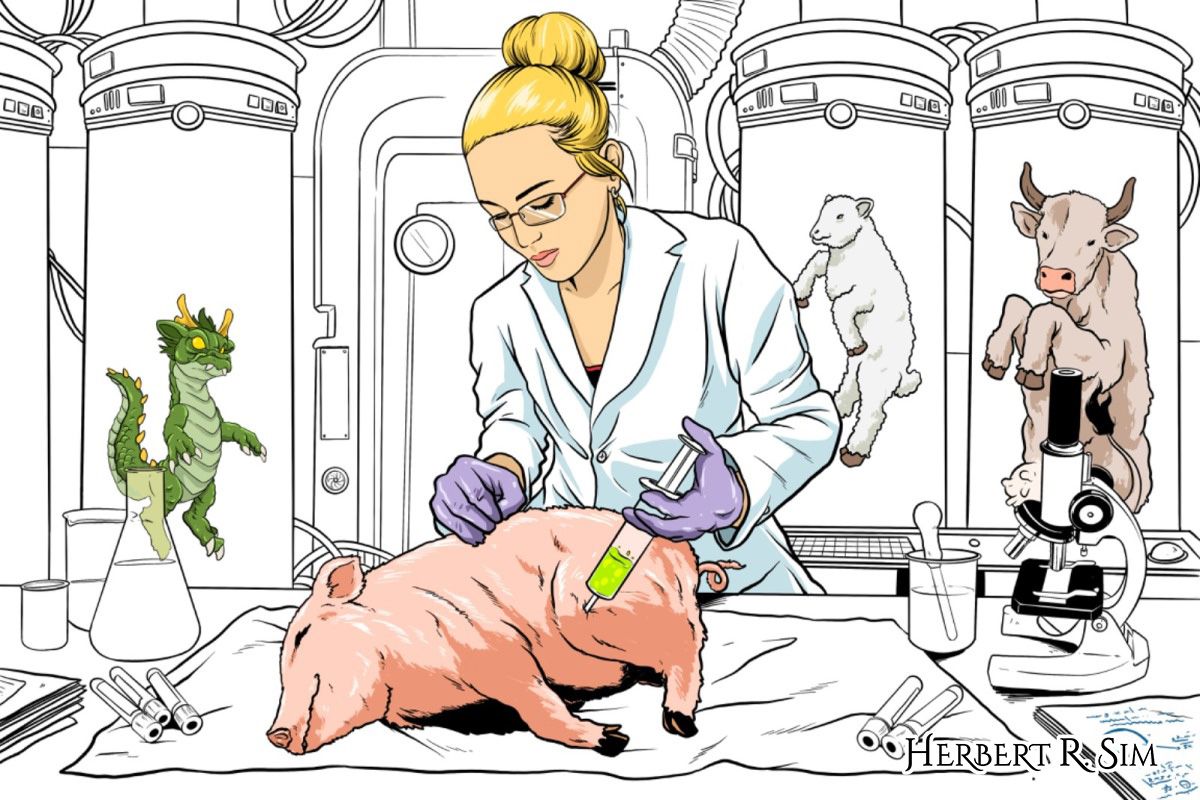

With the viral outbreak of H1N1 Virus (a.k.a. Swine Flu), I drew a science laboratory, with a scientist working on cloning technology.

———————————————–

A massive viral outbreak struck the world in 2009, brought about by the highly contagious H1N1 virus (also known as the swine flu), which fanned waves of panic as the number of cases hit close to 20,000 across 66 countries, including 117 deaths as of writing. On 30 April 2009, Singapore was one of the countries that raised its DORSCON alert level from Yellow to Orange, prompting scientists to uncover new ways that could tackle the virus as well as other potentially fatal infectious diseases.

One of the solutions that came up was cloning, which is the process of creating an organism that is an exact genetic copy of another. In the context of the swine flu, scientists could clone a pig that is immune to the H1N1 virus, before breeding it to conceive a new generation of pigs that could help prevent the spread of H1N1.

Of course, when it comes to combating viral pandemics, cloning has also popped up as a useful and effective alternative solution. Leveraging cloned human cells to develop vaccines may sound far-fetched, but scientists believe that using cloning technology would be quicker and more efficient than relying on traditional vaccine creation processes – the latter taking several months or even years to roll out something viable.

Hollywood’s prediction

The topic of cloning isn’t new and has steadily attracted attention over the years, especially with cloning technology becoming more advanced and executing it is no longer a figment of one’s imagination.

What’s more, the 2005 American science fiction film, Aeon Flux, which starred Charlize Theron, depicted a world where in certain aspects, mirrored what is happening today – a modern society wrecked by the threat of a viral outbreak that could go spinning out of control.

Set in the year 2415, the movie showcased a society that is still functioning, 400 years later, after a viral pandemic had wiped out 99% of humanity. The human population who survived the dreadful outbreak were kept protected within a walled city, but the narrative soon unraveled into a startling discovery that in fact, the ruling regime had kept humanity alive through cloning. While it may seem incredulous at that point in time, such is technology’s explosive progress that replicating such a desire might seem plausible, what with the current slew of advanced equipment and deep research insights available.

Ethical doubts: Are they valid?

Of course, when it comes to cloning, ethicists and other detractors would be quick to point out cloning’s flaws, and the main argument often revolves around the idea of “playing God”. Multiple groups have argued that the ability to create life is a power that should be left alone, to let nature take its own course, and that humans should not be allowed to manipulate the natural order. However, proponents and cloning communities have argued that cloning is a natural extension of a human’s curiosity, a thirst that needs to be quenched and with the added potential to induce significant medical achievements.

Dolly, the world’s first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell, grabbed headlines in 1997 when scientists unveiled the historic breakthrough. What ensued was more than just euphoria or the understanding that cloning might become normalised, but also the unearthing of ethical concerns that one day, cloning humans could, too, become part and parcel of society.

The success of various animal cloning projects also meant the subject was never simply a pipe dream. A cat named CC was cloned by scientists in 2001 and four years later, a dog named Snuppy was cloned – paving the way for further advancements in the area of animal cloning.

Many cloning detractors did not want individuals to be viewed as products, a concept that cloning could reinforce, plus there were also worries that when put in the wrong hands, cloning will be used to shape a superior human race with tailored characteristics, leading to social unrest and an extreme level of elitism.

While fears surrounding the repercussions of cloning abound, research has not stopped in attempting to perfect the art of cloning.

———————————————–

In the illustration, it features the pig being currently experimented on, with other common domesticated farm animals in the background.

———————————————–

The two main types of cloning

In the world of cloning, reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning are the two primary types. Reproductive cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human being – a process that is considered unethical and in fact, banned in multiple countries. Therapeutic cloning, on the other hand, is the creation of embryonic stem cells that can be used for medical research and treatment. This type of cloning is legal in some countries, including the United States.

Therapeutic cloning has been used to create stem cells that can be used for medical research and treatment. One potential use for therapeutic cloning is the creation of organs for transplant, while researchers have also gone further by creating functional organs using cloned cells, including hearts and kidneys. The aim, if successful, is to contribute to the medical field and specifically, organ transplantation which is a crucial procedure that could save multiple lives.

In fact, within the field of assisted reproductive technology, cloning technology can also be utilised to create genetically related children for couples who are unable to conceive naturally. While this may raise ethical questions about the value of genetic diversity, it could provide a solution for people who are struggling with infertility.

Developments in cloning technology

In 2008, a group of scientists revealed that they had successfully cloned human embryos to create stem cells, scoring a critical victory for cloning supporters. The stem cells were used for research purposes, but the breakthrough made the idea of human cloning even more feasible and real, taking scientists one step closer rather than one step back.

As previously mentioned, proponents of human cloning argue that the technology is a plausible method to help address infertility and other genetic diseases. In 2002, a team of researchers at the Reproductive Genetics Institute in Chicago announced the birth of the first cloned human baby, a girl named Eve. The baby was reportedly created using a technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer, which involves taking genetic material from the patient’s skin cells and inserting it into a human egg, before being implanted into the patient’s uterus. As expected, the news caused a global commotion, dividing people into two camps – one praising the team for their groundbreaking achievement, while the other deploring the act as a violation of ethical boundaries.

After the birth of Eve, several human cloning attempts were made, although none of them resulted in a live birth. Various attempts, however, were aimed at creating embryos for stem cell research, while others were intended to, among other things, create a clone of a deceased loved one. The unsuccessful nature of the various projects did result in the conclusion that human cloning can indeed be too risky and ethically controversial to pursue – but judging from the current slew of experiments and research being done, the race to perfect human cloning has never ceased.

The cloning race is heating up

Apart from human cloning, some researchers have also been keen to explore other possibilities, particularly in the field of regenerative medicine. In 2005, a team of researchers at Wake Forest University in North Carolina announced that they had successfully cloned a human kidney. This involved taking a skin cell from a patient with kidney disease and then inserting it into an egg that had its own genetic material removed. The resulting embryo was then implanted into a surrogate mother, from which researchers were able to grow a functional kidney.

The successful operation raised hopes that one day, it may indeed be possible to create customised organs for transplant, using a patient’s own cells. In fact, in the years that followed, there have been other breakthroughs in the field of regenerative medicine, including the creation of artificial skin, bone, and heart tissue – without again, involving human cloning.

The possibility of human cloning has been a burning topic for decades. While some argue that it could lead to significant medical advances and improvements in the quality of life, others assert that it represents an ethically questionable area of research. Despite the perceived notion, significant strides have been made in the realm of cloning, and it remains imperative that policymakers as well as researchers can expertly weigh the potential risks and benefits of cloning. Additionally, they will have to make informed decisions at every juncture along the way, in what may appear to be a complex but ultimately rewarding journey ahead for the cloning community.

———————————————–