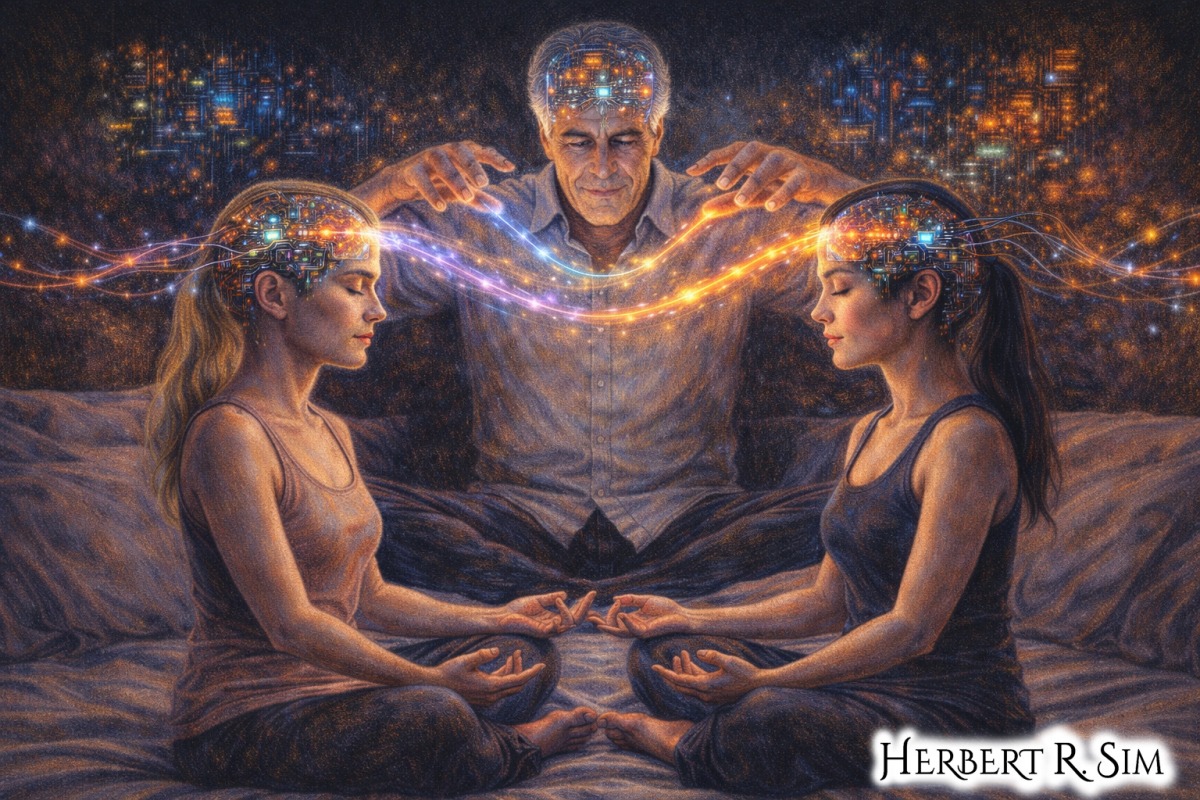

In my illustration above, I feature billionaire – Jeffrey Epstein programming his test-subjects’ consciousness, at his private island – ‘Little Saint James’, using brain-computer interface aka Neurochip.

“Programmable consciousness” sounds like science fiction: press a button and slide into deep focus, effortless compassion, or a mystical sense of unity. Yet, up-to-date, mainstream reporting already documented multiple technologies that can reliably shift elements of subjective experience — attention, mood, motivation, perception, and even aspects of identity — by intervening in neural signaling. The open question is not whether brain-state modulation is possible, but whether we can make it intentional, precise, repeatable, and safe enough to count as “programmable conscious states,” especially via implantable “neurochips.”

To evaluate the plausibility, it helps to distinguish three layers of ambition:

- State nudging: shifting probability toward a desired state (e.g., “more alert,” “calmer”).

- State targeting: invoking a specific, measurable neural signature associated with the target state.

- State programming: reliably inducing, sustaining, sequencing, and terminating states with guardrails — ideally personalized, closed-loop, and resistant to drift.

By 2017, the ecosystem already supported layer (1) in limited forms and offered early hints of layer (2). Layer (3) — true programmability — remained aspirational, but the pathway was becoming visible.

What a “neurochip” can actually control

Implants and stimulation systems modulate consciousness through inputs (stimulation) and sensing (measurement). The most relevant pathways include:

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): electrodes implanted in subcortical targets; clinically used for movement disorders and explored for psychiatric indications. Popular accounts emphasized how DBS can be “futuristic” in effect and ethically complicated when it intersects with mood, motivation, and personality.

- Cortical implants & neuroprosthetics: arrays that record from — and sometimes stimulate — cortex to restore function, and potentially to shape cognition.

- Noninvasive neuromodulation (tDCS/TMS): weaker and less focal than implants, but informative as “prototypes” for consumerization and state control. Reporting highlighted the DIY trend and the uneven evidence base.

To “program” a conscious state, you need at least two things:

- a state model (what neural pattern corresponds to the target), and

- a control policy (what stimulation pattern pushes the brain toward it, without unacceptable side effects).

The difficulty is that brains are not uniform machines; they are adaptive biological systems. The same stimulation can produce different outcomes depending on baseline state, medications, fatigue, context, and individual neuroanatomy — problems already visible in consumer brain-stimulation debates.

Heightened focus: the most tractable “programmable” state

If you had to pick one candidate for early programmability, it would be focus. That is because “focus” can be operationalized through performance metrics and neural signatures (attention networks, oscillatory markers), and the target state is narrower than “transcendence.”

By 2016, journalists described a fast-growing market for “brain hacking” devices and the tension between hype and evidence. Some reports went further, documenting military interest in boosting mental skills with stimulation — an institutional signal that “operationalizable focus” was being treated as an engineering problem.

From a control-systems perspective, a focus-programming neurochip would likely be closed-loop:

- sense attention proxies (behavioral + neural),

- stimulate to correct deviations,

- stop when performance improves or side-effect thresholds trigger.

The practical limiter is not the idea of closed-loop control; it is the risk of unintended tradeoffs. Even noninvasive stimulation raised concerns about people building battery-powered stimulators and using them to chase flow states without medical oversight. IEEE Spectrum’s coverage underscored the regulatory lag: consumer stimulation was already real, while formal guardrails were still catching up.

If “focus as a service” becomes viable, it will likely arrive first as bounded focus — task-linked boosts under constrained conditions — rather than a generalized always-on “productivity mode.”

Empathy: plausible in principle, difficult in definition

Empathy is not a single dial. It includes:

- affective resonance (feeling-with),

- cognitive perspective-taking (understanding),

- prosocial motivation (acting).

Media coverage up-to-date reflected growing awareness that neuromodulation can perturb moral judgment and social cognition — sometimes in unsettling ways. A Scientific American review explicitly referenced how stimulation can alter moral evaluations, emphasizing that the “moral compass” is not immovable under neural intervention.

That supports possibility in principle: if networks supporting perspective-taking or affect regulation can be modulated, empathy components could shift. But “programmable empathy” runs into two hard problems:

- Measurement: you can test reaction time and working memory; empathy is more context-sensitive and vulnerable to demand effects.

- Value alignment: increasing one empathy facet might decrease another (e.g., heightened emotional contagion could impair judgment or boundaries).

In other words, empathy may be “tunable,” but “programmable” risks oversimplifying a multi-dimensional psychological construct — especially if commercialized.

Transcendence: the most attractive and the least controllable

“Transcendence” (mystical unity, ego dissolution, awe) is both compelling and operationally slippery. It can be measured through questionnaires and some neural correlates, but the state is deeply dependent on context, expectation, and interpretation.

Still, it is not absurd to ask whether a neurochip could induce it. Conscious experience depends on large-scale integration, attention, and self-modeling. If stimulation can alter perception (e.g., inducing phosphenes via TMS as part of brain-to-brain experiments) then it can certainly perturb the ingredients of altered states.

However, “transcendence” likely requires more than switching on a node. It may require orchestrating network-level dynamics (synchrony, salience weighting, default-mode modulation), and doing so without destabilizing mood or reality testing. That orchestration is closer to “state programming,” and it is where safety and ethics become acute.

A practical near-term analog is not a single “transcendence button,” but state scaffolding: devices that shift arousal and attentional stance (calm + absorption), making transcendence more probable when paired with training, environment, and intention.

Why “programmability” is harder than “modulation”

Several well-documented issues block straightforward programming:

- Individual variability: what works for one brain may not for another.

- State dependence: stimulation effects depend on baseline state (tired vs. alert, anxious vs. calm).

- Plasticity and drift: the brain adapts; the same input may change effect over time.

- Tradeoffs: improving one domain can impair another (a recurring caution theme in cognitive enhancement coverage).

- Regulatory and ethical lag: consumer and DIY use raced ahead of consensus safety frameworks.

This is why the most credible trajectory is personalized, closed-loop neuromodulation with conservative goals and explicit monitoring — not open-ended “experience design.”

A realistic path: from “neural thermostats” to bounded experience design

Several reports described memory prosthetics and stimulation concepts that resemble a “neural thermostat”: monitor signals, intervene when the system deviates, and aim for a functional setpoint rather than a dramatic altered state. Smithsonian explicitly used this “thermostat” framing in discussing implants intended to support memory function.

Discover Magazine also discussed memory-boosting devices and the broader implications: once you can read patterns and feed them back, the question becomes not only can you enhance, but who decides, who gets access, and what happens under competition pressure.

This is the most plausible bridge to programmable consciousness: start with clinically anchored objectives (depression, PTSD symptoms, attention deficits, motor recovery), then carefully expand into elective enhancement if — and only if — measurement, reversibility, and governance mature.

Conclusion: possible, but constrained, and ethically loaded

By 2017, the public record already supported a sober conclusion:

- Heightened focus is the most technically tractable candidate for intentional induction, especially with closed-loop designs and narrow task framing.

- Empathy may be modifiable in components, but “programmable empathy” is limited by measurement, multidimensionality, and value alignment.

- Transcendence is imaginable as a probabilistic outcome of network modulation, but unlikely to become a deterministic “chip feature” without unacceptable risk and oversimplification.

So: programmable conscious states are possible in principle, but the near-term reality looks less like “select an emotion” and more like bounded state steering — a careful, feedback-controlled nudge toward measurable targets, with governance robust enough to handle identity-level stakes.