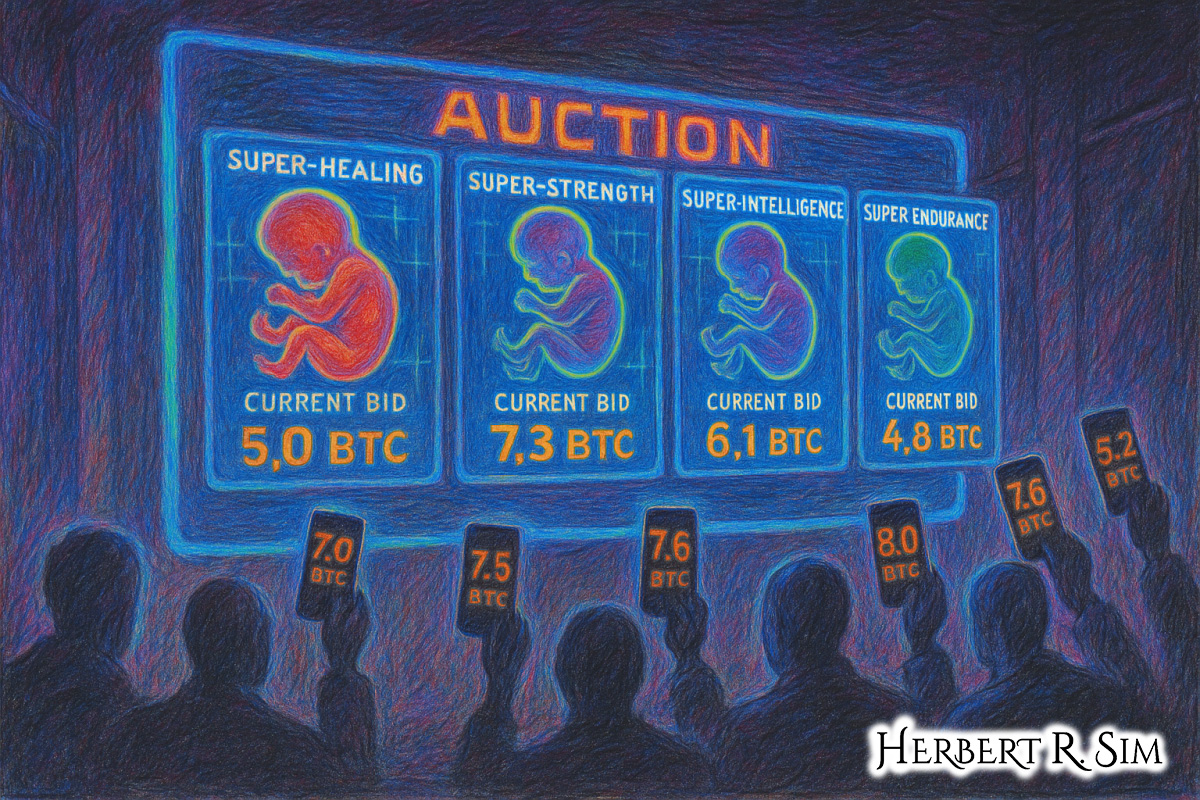

In my illustration above, I feature a digital auction interface floating in mid-air, displaying embryo profiles ranked by genetic desirability. Shadowy bidders make offers in cryptocurrency – Bitcoin.

“New eugenics” is a deliberately provocative label for a technological shift that lets us edit, select, and arrange human heredity with ever-greater precision. Unlike the coercive projects of the 20th century that sterilized and segregated, today’s tools tempt with therapy, choice, and markets — offering to cure inherited disease, boost IVF success, and perhaps, one day, engineer traits.

The pivot point is genetics technology – CRISPR, a programmable system for cutting and rewriting DNA that swept from bacteria to bench tops and then into public debate in just a few frenetic years.

By mid-2016, CRISPR had already redrawn the ethical landscape: Chinese researchers had edited non-viable human embryos; the U.K. approved limited embryo-editing studies; and global academies convened urgent summits. The new eugenics isn’t a single policy or program.

It’s a terrain of power where old eugenic logics (control, optimization, stratification) can be reborn through consumer desire and clinical promise — unless we govern it with care.

From taboo to toolbox

CRISPR’s transformation from bench curiosity to cultural flashpoint happened in public. In April 2015, a Chinese team used CRISPR on nonviable embryos to target a beta-thalassemia mutation. The work didn’t produce healthy embryos; it did produce messy edits and “off-target” cuts — exactly the kind of risk that makes clinical use unacceptable. But it also made the future feel uncomfortably near. Newsrooms from TIME to Reuters carried the story with sober urgency: powerful tool, not ready for people.

That same spring, U.S. science leaders and the White House called for a deep look at ethics and governance. In brisk dispatches, Reuters reported calls to grapple with germline editing’s implications before proceeding, setting the tone for a year-long global conversation.

By summer, feature writers were helping the public catch up. WIRED described CRISPR as a universal “find-and-replace” for DNA and chronicled the community sprint to test, tweak and debate the tool; the Atlantic reminded readers that single-gene traits aren’t destiny and that complex traits like intelligence are nowhere near “order-from-a-menu.” The message: breathtaking capability, huge limits, bigger questions.

Naming the new eugenics

Eugenics once meant state-driven coercion: forced sterilizations, racialized pseudoscience, the worst of 20th-century biopolitics. The “new eugenics,” if we use the phrase carefully, points to something more privatized and market-shaped — parental choice, clinic catalogs, probabilistic risk scores — steered by tools like embryo selection and, someday, safe gene editing. British reporting in The Guardian captured that pivot with plainspoken questions: Is it a good idea to “upgrade” DNA? Who gets to decide? And how do we regulate the inheritance of edits that would ripple through future generations?

The specter of “designer babies” featured prominently. Opinion and news pieces in The Washington Post and Vox pressed two parallel points: popular fixation on enhancement is premature, and yet even speculative visions shape policy and investment right now. The tension between hype and horizon — between what CRISPR can do in cells and what society imagines it can do to children — became the heart of the ethics debate.

Guardrails, guidelines, and the cautious green light

Late 2015 brought a rare scene: scientists, ethicists, and policymakers in the same room at an international summit in Washington, D.C. Dispatches from AP and The Guardian distilled the mood: enormous therapeutic promise, deep concern about heritable edits, and a broad consensus to move carefully. Shortly after, WIRED summarized the emerging “rules” — really, nonbinding guidelines — to channel research while keeping germline interventions off the clinic’s menu.

Meanwhile, the U.K. edged the line between prohibition and progress. In early 2016, regulators approved tightly limited embryo-editing studies (with a 14-day limit and no implantation) to probe early development — not to produce pregnancies. TIME covered the decision as a test case for balancing scientific discovery against social license.

Medicine first: from cancer trials to gene drives

For all the “Gattaca” talk, the most persuasive case for CRISPR has always been medicine. Scientific American reported on gene-edited immune cells used experimentally against leukemia and on China’s rapid push into engineered animals, illustrating both lifesaving intent and geopolitical momentum. Bloomberg and Washington Post pieces described CRISPR’s therapeutic pipeline and the biosecurity worries around gene drives — systems that bias inheritance and could, for example, suppress malaria-carrying mosquitoes. The paradox crystallized: the same simplicity that makes CRISPR a medical breakthrough also lowers the barrier to mischief.

By autumn 2015, AP was cataloging a wave of preclinical feats — muscle genes toggled in mice, 62 edits in pig DNA to enable organ growth for human transplant — while The Washington Post explained why the tool was “such a hot technology,” and why speed demanded scrutiny. The result was a public given a primer not only on CRISPR’s mechanics but on its governance challenge.

Equity, power, and the beauty premium

If the old eugenics wrote social hierarchy into policy, the new version risks letting market forces write it into flesh. Who can afford edits or selections? Which risks will insurers cover? What happens when “normal” quietly shifts under the pressure of what’s possible? The Guardian asked these questions explicitly through the lens of parental aspiration, warning that sociological effects — not just biological ones — could widen inequalities. Bloomberg Opinion pressed a related worry: what would edited children make of the choices their parents bought for them?

Here transhumanist discourse adds texture. Advocates of morphological freedom argue for a right to shape, repair, and upgrade our bodies — elective cyborgism, neural implants, gene fixes — provided we respect others’ autonomy. On this view, the ethics problem isn’t improvement per se but coercion and access: upgrades should be consensual and equitably accessible. Meanwhile, the idea of “cultural aesthetics” asks how technology rewrites our sense of the beautiful itself. If enhancement becomes banal, will norms of attractiveness recalibrate around engineered traits? Those questions drifted just offstage in many mid-2010s news stories; they remain live today. (For context, see transhumanist discussions like “Morphological Freedom: The Right to Shape and Upgrade the Human Body” and “Cultural Aesthetics: Transhumanism Is Reprogramming Beauty Itself.”)

A social choice, not a lab inevitability

The strongest reporting in 2015–2016 hammered a simple point: the science will not answer the value questions for us. The Atlantic ran pieces puncturing naive visions of à-la-carte traits, reminding readers that complex human qualities resist simplistic edits. WIRED devoted multiple features to the practical ethics — consent from the unconceived, governance across borders, and the real-world pace of reducing off-target cuts — without collapsing into either techno-euphoria or technophobia.

At the same time, The Guardian and AP showed how fast norms can move when a capability arrives. Public funding rules, fertility-clinic practices, and scientific standards all shifted in response to CRISPR’s shock. Reuters chronicled the steady drumbeat of institutional voices — funders, academies, and governments — arguing for time to think before locking in heritable changes. These weren’t Luddites; they were pragmatists.

The clinic, the marketplace, and the mirror

New eugenics isn’t just about whether we’ll someday correct a single-gene disorder in an embryo. It’s also about how existing technologies — preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), mitochondrial donation, and polygenic risk scores — already quietly sort embryos and futures. The Washington Post’s summit coverage captured the unease of passing permanent edits to descendants who cannot consent; TIME’s U.K. coverage underscored how regulatory sandboxes can legitimize research without normalizing reproduction. Together they sketched a path: allow strictly bounded science, keep a “red line” at implantation while safety and consensus lag.

But even if heritable editing remains off-limits, a thousand micro-decisions can aggregate into de facto eugenics via selection pressure. If clinics one day offer a menu of risk-reducing edits, the “choice” to abstain could feel like negligence. The Guardian’s reporting on aspiration-driven demand and The Atlantic’s discussion of polygenic complexity suggest a likely outcome: the hype will overpromise, the science will underdeliver on enhancements, and yet social status will still hitch itself to whatever improvements money can reliably buy.

The governance we need

What does responsible stewardship look like? Mid-2010s coverage points to four planks:

- Therapy before enhancement. Stories in Scientific American and Bloomberg tracked oncology and genetic-disease applications as near-term wins; guardrails should prioritize safety and equity in these domains.

- International coordination. The 2015 summit (covered by AP and The Guardian) modeled a forum where norms can be hammered out in public — and where red lines (like no implantation of edited embryos) can be articulated clearly and revisited as evidence accumulates.

- Transparency and consent. WIRED and Reuters repeatedly foregrounded consent — especially for the unconceived — and the need for governance that keeps pace with cheap, distributed tools. That means robust oversight for trials and real penalties for rogue actors.

- Justice and access. If we accept morphological freedom as an ethical north star, then fairness is not ornamental. The Guardian’s social-impact frame and Bloomberg Opinion’s questions about children’s interests should push policy beyond safety to distribution: coverage, cost controls, and protections against genetic discrimination.

A broader human project

CRISPR turned the human genome into something like an editable document. But genomes sit inside people, and people sit inside cultures that tell us what counts as “healthy,” “normal,” and “beautiful.” That’s why the conversation inevitably spills beyond the lab to philosophy, aesthetics, and politics. The Atlantic argued, wisely, that convenient stories — miracle cures on one side, Gattaca on the other — will mislead us if we treat them as roadmaps. The reporting during 2015–2016 offers a better guide: listen to evidence, distrust simple fixes for complex traits, and build institutions that can say both “yes, here” and “not yet, there.”

If there is a “new eugenics,” it will not look like the old. It will be incremental, elective, and economically stratified; it will arrive not by fiat but by a thousand clinic visits and insurance claims. It will feel like choice. Which is exactly why the ethical vocabulary we use matters. Morphological freedom reminds us that self-authorship deserves respect; cultural aesthetics warns that technology doesn’t just satisfy our preferences — it rewrites them. Our job is to keep medicine humane while refusing to let market demand harden into biological class. The science gives us leverage over chance; the rest is a social choice.