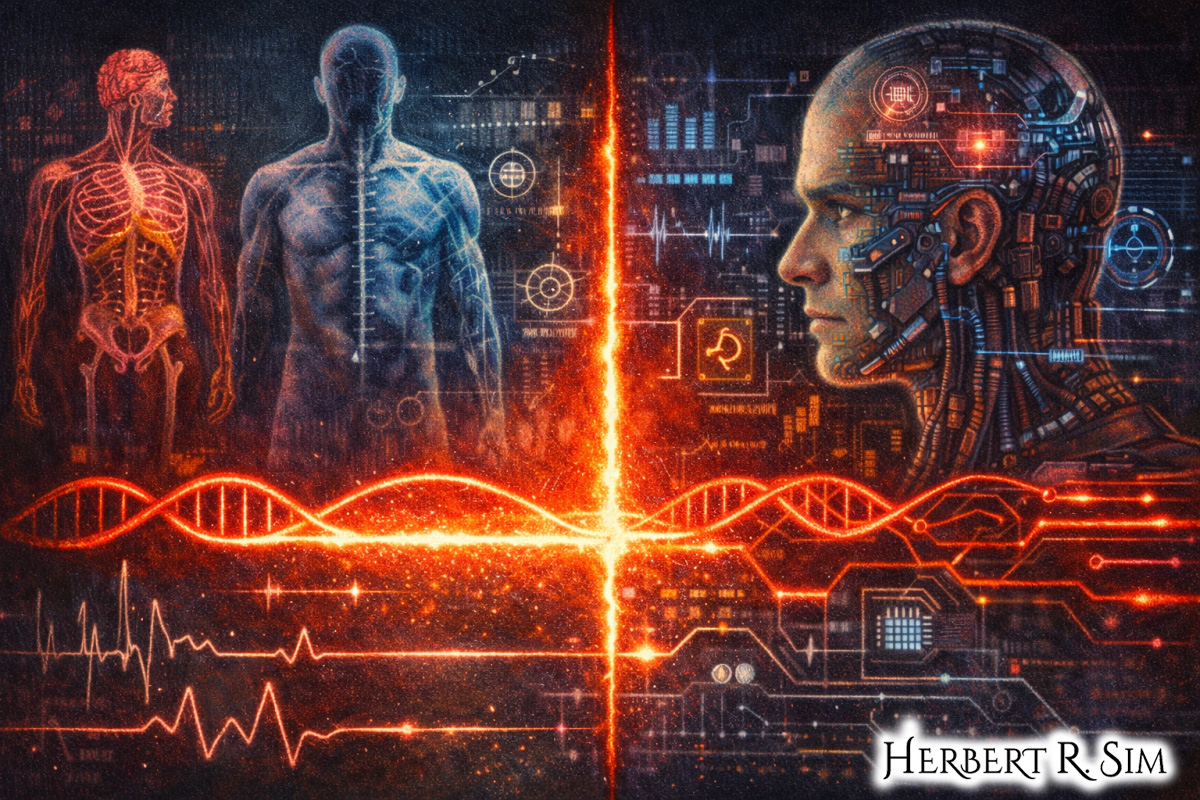

In my illustration, I drew a “red line” running across the image that doubles as a neural circuit or DNA strand. On one side: human anatomy diagrams; on the other: synthetic enhancements, circuitry, gene-editing visuals. Symbolising ethical boundaries embedded in biology, blurring lines between medicine and militarization.

“Military transhumanism” is a useful label for a simple reality: armed forces have always tried to push human performance beyond ordinary limits. What is new is the convergence of biology, robotics, and information systems into an integrated enhancement stack — genetic interventions, neuropharmacology, powered exoskeletons, networked sensors, autonomous robotics, and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs).

The objective is no longer merely to equip the soldier, but to upgrade the soldier-system as a platform — stronger, faster, more alert, better connected, and potentially more lethal. That ambition raises strategic escalation risks and sharp ethical red lines: what must remain off-limits, and what guardrails are credible when rivals assume you will push until stopped?

From “equipment” to “human-machine system”

Exoskeleton programs illustrate how quickly enhancement shifts from concept to procurement pressure. Early DARPA-linked prototypes such as Berkeley’s BLEEX promised to make heavy loads feel dramatically lighter — less a costume than a wearable logistics multiplier. That vision has recurred for two decades because it solves a real operational constraint: infantry overburden. Once a system can transfer load through a powered frame, the next step is optimization — energy efficiency, endurance, thermal management, and usability in real terrain. Wired’s early coverage of BLEEX made explicit what militaries value: reduced fatigue, higher mobility under weight, and extended operational tempo.

A decade later, the U.S. Army was testing systems like Lockheed’s HULC, again framed not as science fiction but as an attempt to reduce injury and expand what a human can carry and lift in the field. IEEE Spectrum’s reporting on Raytheon/Sarcos XOS 2 made the same point in pop-cultural shorthand — an “Iron Man” trajectory — but anchored it in the mundane: load-bearing and injury reduction. Gizmodo’s io9 coverage (via an “Agent Coulson tests a real exoskeleton” hook) similarly normalised the idea that powered suits are a near-term military adjunct, not a distant fantasy.

These systems are often sold as defensive, humanitarian even: fewer musculoskeletal injuries; faster evacuation; better endurance. But enhancement rarely stays purely “protective.” Increased strength and reduced fatigue change the tactical envelope: soldiers can carry more ammunition, heavier sensors, and potentially heavier weapons. That drives adversary adaptation. If one side can sustain a heavier loadout without losing mobility, the other side must counter — by upgrading its own forces, shifting to stand-off weapons, or targeting the enhanced soldier’s vulnerabilities (power supply, joints, communications links).

Neuroenhancement: from stimulants to “synthetic telepathy”

The more provocative frontier is neuroenhancement: altering cognition, vigilance, decision speed, and even communication. The Independent’s 2011 discussion of “super-soldiers” captured a key military interest: chemically muting fatigue, stress, fear, and the psychological cost of combat — while warning that such “shortcuts” can corrode moral judgment and long-term well-being.

BCIs push the same logic further. The Guardian’s account of BrainGate foregrounded therapeutic goals — helping paralysed people control cursors or devices — but also noted the shadow question: once neural signals can be decoded reliably, military applications become difficult to ignore. Discover’s 2011 feature on “synthetic telepathy” described Army-funded work aimed at thought-based communication — silent coordination without speech or hand signals. The Economist, writing on brain–computer interfaces in 2011, treated BCIs as a plausible next step in human–machine integration, with obvious security and governance implications once signals can be read, transmitted, or spoofed.

The strategic risk is not only “better soldiers,” but new attack surfaces. An enhanced soldier dependent on sensors, data links, or neural interfaces becomes vulnerable to jamming, intrusion, deception, or capture of biometric/neural signatures. Even without speculative mind-reading, any interface that translates intent into action creates a pathway for adversarial interference.

Robotics: the externalised “enhancement” of force

Military transhumanism is not only about modifying bodies; it is also about shifting risk from humans to machines, and then linking humans and machines tightly enough that the boundary blurs. Wired’s 2011 piece on DARPA/Boston Dynamics’ “Cheetah” robot (building on BigDog) exemplified this: robots intended to move fast, carry loads, and operate in environments that punish humans. Popular Science’s 2011 “First Steps of a Cyborg” emphasised that military funding is a major driver in exoskeleton development, even when the public-facing story focuses on medical mobility.

Robotics becomes ethically combustible when autonomy creeps toward the lethal decision. Wired’s 2008 discussion of “robot war” argued that the real issue is not a Hollywood “Terminator” moment, but incremental autonomisation — more target recognition, more automated tracking, less human deliberation in the kill chain. The Atlantic’s 2011 “Drone Ethics” briefing treated drones as a moral and political stress test: reduced risk to one’s own forces can lower the threshold for using force, while amplifying resentment and blowback among those who feel permanently surveilled or targeted.

This is enhancement-by-proxy: you do not need to genetically upgrade a soldier if you can give them persistent ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance), machine-speed targeting assistance, and robot “mules” that carry and move for them. But the escalation logic is similar: when one side can project force with fewer casualties, the other side searches for asymmetric counters — cyberattacks, anti-drone systems, hostage-taking, human shields, and attacks on civilian infrastructure that supports the high-tech force.

Genetics and the “irreversible” threshold

Genetic enhancement is the most ethically loaded because it suggests heritable or long-duration changes and raises consent problems that are hard to resolve in hierarchical organisations. Even where current military projects are not literally editing embryos, the direction of travel — biological optimisation, selection, and long-term physiological tuning — creates a “ratchet effect.” Once rivals suspect one side is exploring genetic advantage, they may feel compelled to do the same, and verification is difficult. Unlike a tank or missile, a genome-level program can hide behind legitimate biomedical research, making arms-control style transparency challenging.

The public discourse before 2012 often circled this point indirectly — through fatigue drugs, stress inoculation, and neural modulation — because those were closer to deployment. The deeper ethical principle remains: interventions that are irreversible, heritable, or identity-altering demand far stricter constraints than reversible equipment upgrades.

The escalation problem: why “defensive” enhancements rarely stay defensive

Enhancement technologies tend to trigger escalation through four pathways:

- Capability mirroring. If exoskeletons allow heavier loads and longer patrol duration, an adversary either builds similar systems or invests in counters (ambush tactics, IEDs, precision fires). The Verge’s 2011 coverage of DARPA’s “AlphaDog” robot mule highlighted how a support technology can still reshape ground combat by extending what small units can carry and how long they can operate.

- Doctrinal drift. Drones and robotic systems can change political decision-making. When casualties decrease on one side, leaders may authorise missions that would previously have been politically untenable, reinforcing the cycle of retaliation and counter-retaliation. The Atlantic’s framing of drone ethics foreshadowed this dynamic.

- Dependency and vulnerability. Networked enhancement creates fragile dependencies: power, software, bandwidth, and supply chains. Adversaries exploit those weak points rather than competing symmetrically.

- Norm erosion. The more war looks like a competition of engineered systems, the easier it becomes to treat humans — both combatants and civilians — as parameters. The Independent’s warning about “zoned-out zombies” was a moral argument, but it also hints at strategic instability: forces that suppress fear, fatigue, or guilt may behave in ways that generate atrocities, insurgency fuel, or uncontrolled escalation.

Ethical red lines: what should not be crossed

A credible ethical framework for military enhancement needs bright lines, not only “best practices.” Several red lines stand out.

- Non-consensual or coercive enhancement. Military hierarchy compromises voluntariness. Even “opt-in” enhancements can become career filters. Ethical policy should prohibit compulsory invasive enhancements and require independent medical oversight.

- Irreversible identity-altering interventions without compelling therapeutic justification. BCIs and neurostimulation can be therapeutic, but military use aimed at personality, emotion suppression, or moral “dulling” should be treated as presumptively impermissible. The Guardian’s BrainGate coverage makes clear how quickly therapeutic tools invite dual-use speculation.

- Delegation of lethal decision-making to machines. Even before 2012, debate was intensifying around autonomy creep. Wired’s “Robot War Continues” argued that the slope is incremental and difficult to regulate once systems are built. A sensible red line is “meaningful human control” over lethal force — humans must remain responsible agents, not rubber stamps for algorithmic recommendations.

- Enhancements that externalise harm or accountability. If a system makes it unclear who is responsible — programmer, commander, operator, or machine — then the system undermines the moral architecture of the laws of war. Diminished accountability is not a side issue; it is an accelerant.

Governance: what “real” guardrails look like

The uncomfortable truth is that ethics statements do little if adversaries race ahead. Guardrails must therefore be operational:

- Doctrine-first constraints. Require commanders to justify when enhancement systems are necessary and proportionate, not merely advantageous.

- Security-by-design for enhancement tech. Treat BCIs and soldier-worn systems as high-risk cyber-physical assets; design against spoofing, data exfiltration, and coercive capture.

- Post-service obligations. If militaries benefit from enhancements, they owe lifetime monitoring and care for downstream harms (neurological, psychological, musculoskeletal).

- Transparency where feasible. Even partial disclosure about categories of enhancement research can reduce worst-case assumptions and slow escalation.

The Verge’s 2012 reporting on DARPA’s “Avatar” concept — human-supervised robotic surrogates — captures both the promise and the governance challenge: distancing humans from the battlefield can reduce immediate casualties while increasing the temptation to use force.

Conclusion

Military transhumanism is not a single technology; it is a trajectory toward integrated human–machine warfighting systems. Exoskeletons, robotics, and BCIs can produce real humanitarian benefits — fewer injuries, restored mobility, better rescue capability. But the same tools can erode restraint, deepen escalation pressures, and create new forms of vulnerability and coercion. The ethical red lines that matter most are the ones that preserve human agency, accountability, and informed consent — especially where interventions are invasive, identity-altering, or tied to lethal force. Without enforceable guardrails, enhancement will not merely change the soldier; it will change the political economy of war itself.