How transhumanist technologies blur the line between therapy and enhancement.

Who Decides What a “Normal” Body Looks Like in the Age of Enhancement?

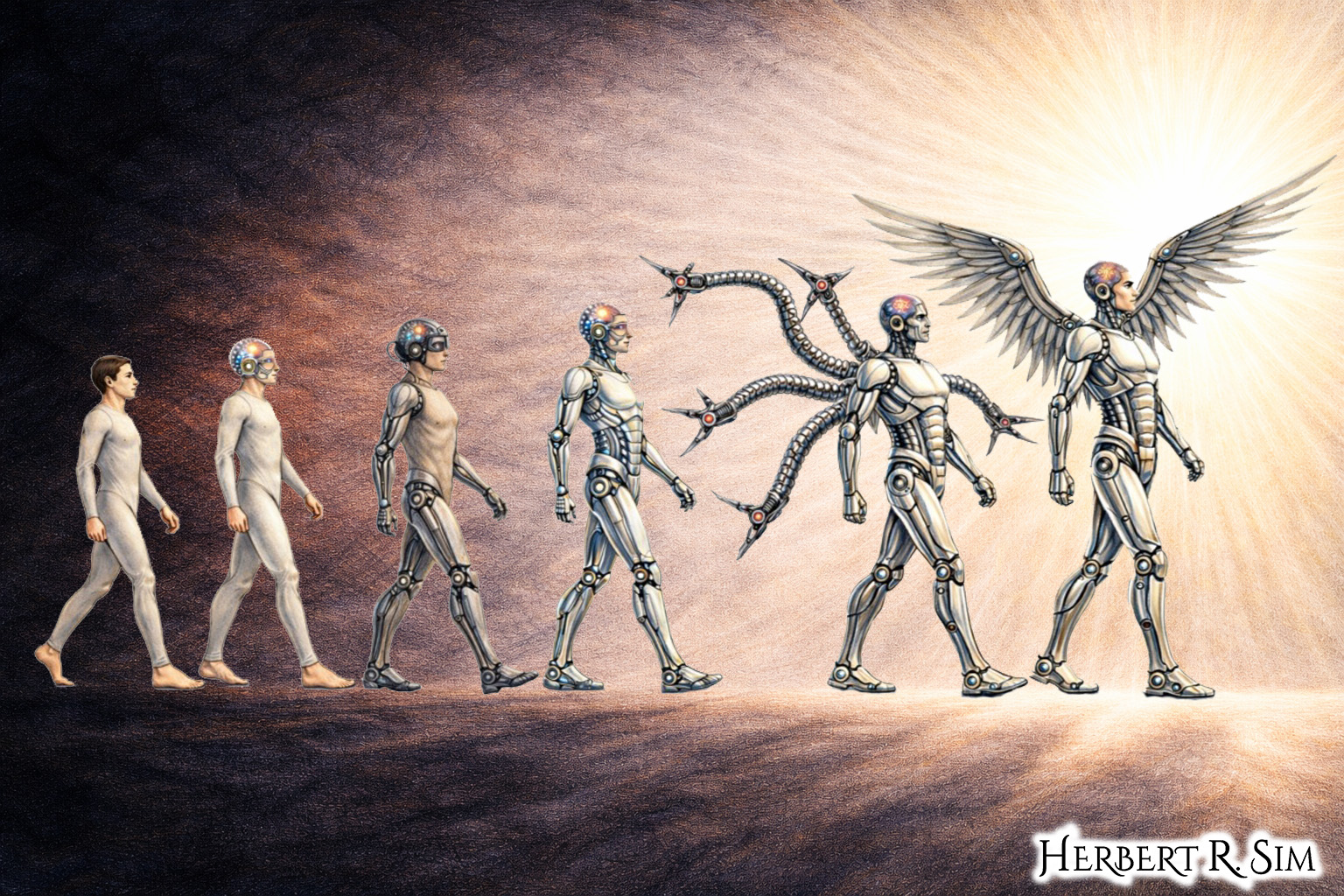

In my illustration above, I showcase the human to cyborg evolution, transcendence towards bionics, towards becoming a cyborg — notice the height increments, and robotic upgrades — with additional limbs (inspired by ‘Dr Octopus’), and mechanical wings.

The boundary between “therapy” (restoring a person to health) and “enhancement” (making a person “better than well”) looks crisp in policy memos and bioethics primers. In practice — especially where disability meets emerging technologies — it is unstable, negotiated, and political. What counts as “normal function” is not a neutral scientific baseline; it is a social decision with legal, economic, and cultural consequences.

Transhumanist-leaning technologies — advanced prosthetics, brain–machine interfaces, sensory implants, exoskeletons, genetic editing and cognitive enhancers — bring that decision to the surface by forcing a question that disability communities have long asked: normal according to whom, and for what purpose?

Normal as a moving target

Disability politics has often centered on two competing intuitions. One treats disability as a deficit located in bodies — something to be fixed. The other treats disability as a mismatch between bodies and environments — something to be accommodated, redesigned around, and valued as part of human variation. Transhumanist technology can appear to “resolve” the tension by offering new functional capabilities, but it frequently relocates the argument rather than ending it. When a device changes what a body can do, it also changes what society expects bodies to do.

Consider the rhetorical framing around bionic vision. In 2010, coverage of retinal implants emphasized partial restoration — recognizing shapes and objects, reclaiming some navigational ability. The narrative reads as therapy: a response to a defined impairment with a clinical endpoint (seeing again). Yet even at that early stage, the technology is not merely returning a prior faculty; it is translating the visual world into new signal systems and training users to interpret them — effectively a new sensory skillset rather than a simple “repair”. The question becomes whether the “goal” is normal sight, functional independence, or some hybrid that alters the meaning of vision itself.

Therapy that scales into enhancement

A recurring pattern in human-augmentation technologies is what might be called therapeutic escalation: tools built for clinical restoration become platforms that can exceed typical human performance once cost, miniaturization, and iteration catch up.

Prosthetics are the clearest case. Modern designs increasingly embed computing, energy return, and fine-grained control — features that can be framed as restoring mobility for amputees while also enabling performance that does not map neatly onto biological limbs.

Public debate over Oscar Pistorius’s carbon-fiber “blades” made this tension mainstream: were the prosthetics merely compensatory, or did they confer competitive advantages? The controversy was not only about sports. It was a proxy fight about who gets to define “fair” ability, and whether “normal” is a biological category or a rules-based one.

Even when analysts disagreed on the empirical question of advantage, the political stakes were evident: if prosthetics can sometimes outperform flesh, then disability is no longer only a “lack.” It becomes, at least in select contexts, a site of technical possibility — raising uncomfortable questions about whether enhancement will be sought by people without disabilities, and whether disabled users will be pressured to adopt ever-more-advanced devices to be deemed employable, insurable, or “independent.”

From assistive to augmentary: exoskeletons and the redefinition of walking

Exoskeletons began as assistive robotics — help paraplegic users stand, walk, or train gait. Early reporting highlighted dignity and access: standing eye-to-eye, moving through space without a wheelchair, the psychological weight of “walking again.”

But exoskeletons also sit naturally inside transhumanist imaginaries: wearable machines that can, with enough power and control, make users stronger, faster, and more durable than baseline physiology. Popular coverage has openly gestured toward that dual-use trajectory — helping wheelchair users become ambulatory while also foreshadowing “bigger-stronger-faster” applications.

Once the same mechanical frame can serve rehabilitation and augmentation, “therapy vs enhancement” is no longer a device property; it becomes a question of intent, regulation, and distribution. If insurers will reimburse only when a user meets a medical-necessity definition, then technologies that look “too good” risk being categorized as luxuries — even if they are the most effective route to participation. Conversely, if enhancements are paid for privately, then ability itself becomes stratified: “normal” is what affluent people can purchase.

Brain-machine interfaces and the politics of agency

Brain–machine interfaces (BMIs) intensify the ambiguity because they don’t just replace a limb; they re-route intention into engineered action. Media coverage of brain-controlled robotics has repeatedly emphasized the restoration of agency — controlling a robotic arm, performing tasks once impossible, turning thought into movement.

Yet the same technology stack — neural decoding, real-time actuation, feedback loops — can plausibly migrate from therapy into performance optimization. That possibility is why some reporting framed BMI projects as both hope and spectacle: a compelling demonstration of “walking again,” but also a high-profile narrative that can outpace incremental clinical realities.

This is where disability politics matters most. If society treats BMIs as heroic “overcoming,” it can unintentionally valorize a narrow ideal: disabled people are celebrated when they approximate able-bodied norms through technology, and neglected when they demand non-technological accommodations (ramps, interpreters, flexible work design). The technology becomes a moral script: you could be normal, if you tried (or if you implanted the right device).

Sensory implants: restoration, identity, and cultural loss

Not all disability communities interpret “restoration” the same way. Deafness debates — especially around cochlear implants — have long illustrated how medical framing can collide with cultural identity. A cochlear implant can be described as therapy for hearing loss, but it can also be experienced (or politicized) as a threat to Deaf language communities, institutions, and ways of being. In that framing, “normal hearing” is not a universal good; it is a majority preference with assimilationist effects.

Although the sources below focus more on visual prosthetics, the pattern carries across sensory tech. When an implant changes not only function but also community membership and language practice, the therapy/enhancement boundary is inseparable from questions of minority rights and cultural continuity. “Normal” becomes a demographic outcome: which populations persist, and which are engineered away.

The bionic eye as a case study in “good enough” normal

Retinal prostheses like the Argus II were widely framed as breakthrough therapies — FDA approval, clinical availability, concrete functional gains.

But even sympathetic reporting also disclosed the economic and experiential realities: high costs, limited resolution, a visual experience unlike ordinary sight, and a learning curve that resembles mastering a new interface rather than regaining a former sense.

Here the politics of “normal” shows up in a practical question: what threshold of function counts as success? Is “normal” reading fine print, recognizing faces, navigating crosswalks, identifying contrast, or simply participating in public space with less assistance? These are not purely clinical endpoints. They are social participation metrics, and they vary by environment. A city designed around clear audio cues, high-contrast signage, and accessible navigation changes what the implant must accomplish to be considered “restorative”.

Consumerization: from medical device to lifestyle interface

As prosthetics and implants converge with mainstream consumer electronics — smartphone control, app ecosystems, software updates — the line blurs again. A bionic hand controlled via a mobile interface can be framed as empowerment and personalization, but it also pulls disability technologies into the market logic of upgrades and planned obsolescence.

In that world, “normal” is not only a body state; it is a product tier. The “best” version of ability becomes something released annually, bundled with service contracts, and unevenly available across countries and health systems.

Pharmaceutical enhancement: when normal focus becomes a performance metric

Cognitive enhancers sharpen the therapy/enhancement dilemma because the target — attention, wakefulness, motivation — already exists on a continuum in everyday life. Coverage of “smart drugs” such as modafinil often highlights a migration: developed for clinical sleep disorders, used by healthy students and professionals to extend productivity.

What makes this politically relevant to disability is that many disabled people already navigate institutions that reward uninterrupted output and penalize bodily variance. If enhancement becomes normalized in competitive settings, the baseline expectation shifts. The result can be coercive: not an explicit mandate, but a soft pressure that makes refusal costly. “Normal” becomes “enhanced enough to keep up.”

Genetic editing and the new “normal”

If prosthetics and neural interfaces blur therapy and enhancement at the level of function, genetic editing blurs the line at the level of biology itself. Once the target of intervention is not a limb or a sensory pathway but the genome, “restoration” no longer means returning an individual to a prior state. It can mean rewriting the conditions under which bodies—and future bodies—come into being.

This matters for disability politics because genetic interventions can be framed simultaneously as compassionate medicine and as population-level normalization. In the transhumanist register, gene editing is often discussed as a platform technology: a way to remove disease, increase resilience, or optimize traits. But in the disability register, the same language can sound like a promise to make certain kinds of people less likely to exist. The ethical controversy is not only about safety, but also about which differences are treated as legitimate forms of human variation versus “errors” to be corrected.

The contemporary inflection point for this debate arrived when CRISPR-based gene editing began to be described in mainstream outlets as a step-change in accessibility—faster, cheaper, and more straightforward than prior gene-editing techniques. That shift matters politically: when powerful interventions become easier to deploy, social pressures can scale with them. What begins as therapy for rare, severe disorders can slide toward “preventive” editing, then toward elective optimization—especially if institutions (schools, employers, insurers, states) start to treat edited traits as risk management.

At that point, “normal” becomes an engineering target. The therapy/enhancement boundary is no longer a clinical distinction but an argument about governance: who sets acceptable endpoints, how consent works across generations, and whether the pursuit of reduced suffering can coexist with disability communities’ demands for equal inclusion without requiring biological conformity.

Governance: fairness, access, and the right to remain different

As these technologies proliferate, governance debates often default to the therapy/enhancement distinction because it is administratively convenient: therapy is reimbursable and ethically palatable; enhancement is elective and morally suspect. But disability politics exposes how that boundary can harm the very people it claims to protect.

If a device exceeds “typical” performance, will it be denied as non-essential even when it is the best route to independence? If a technology is categorized as enhancement, will it become a luxury market — exacerbating inequality in education, work, and mobility? And if “normal” is defined statistically, will minority embodiments be treated as errors to be corrected rather than identities to be supported?

A more realistic framework treats these technologies as capability tools whose ethical status depends on context: who chooses, who pays, who benefits, and what alternatives exist (including non-technological accommodations). In this view, the key political question is not “therapy or enhancement?” but “what kind of society are we building when we set the baseline for participation?”

Transhumanist technologies do not simply blur a line; they relocate power. They can expand agency and reduce suffering, but they can also redefine normal in ways that intensify social pressure, deepen inequality, and narrow the space for disability as a legitimate form of human difference. The task is to ensure that “better” does not silently become “mandatory,” and that the future of augmentation includes the right not only to change bodies — but also to change environments, institutions, and expectations.