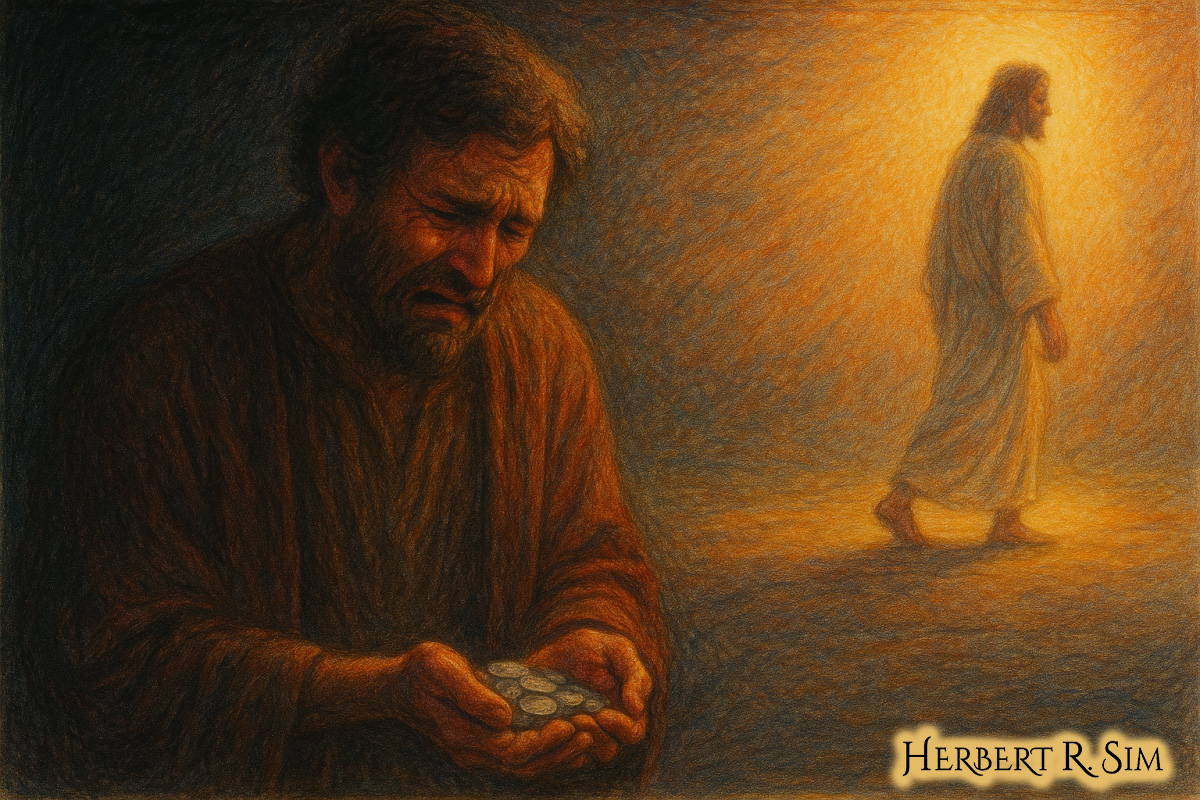

In my illustration above, featuring “Judas in Shadow, Jesus in Light”.

The Gospel of Judas is one of the most controversial Christian texts to emerge in modern times. Announced to the world in 2006 by the National Geographic Society, this formerly lost gospel promised a stunning twist: Judas Iscariot, long vilified as Christianity’s arch-betrayer, appears not as a villain but as the disciple who understands Jesus best and cooperates in a divinely ordained plan.

Yet behind the headlines lies a much more complex story — about ancient Gnostic Christianity, the modern antiquities market, media hype, and an intense scholarly fight over what the text really says.

From Egyptian tomb to media spectacle

The only known copy of the Gospel of Judas survives in Codex Tchacos, a Coptic papyrus manuscript probably copied in the 3rd–4th century CE from a Greek original composed around the mid-2nd century.

According to reconstructions pieced together by journalists and scholars, the codex was likely unearthed in the 1970s near El Minya in Egypt, then passed through a murky chain of dealers, bank vaults and failed sales. At one point, the codex reportedly sat for years in a safety-deposit box in Hicksville, New York, where poor storage accelerated its decay.

Eventually Swiss dealer Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos entrusted it to the Maecenas Foundation, which partnered with the National Geographic Society. National Geographic funded conservation, radiocarbon dating, ink analysis, and the first modern translation, then launched a high-profile global media rollout: magazine features, books, a website, and a prime-time TV documentary in April 2006.

Major outlets quickly followed. The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, TIME, CBS News, Al Jazeera, NPR and others ran front-page stories and broadcast specials that framed the gospel as a potential rehabilitation of Judas.

What the Gospel of Judas actually says

The Gospel of Judas is not a narrative like the canonical gospels. It is a revelatory dialogue: a series of conversations between Jesus and his disciples, with special focus on Judas. According to the text’s own title, it is “the secret account of the revelation that Jesus spoke in conversation with Judas Iscariot during a week, three days before he celebrated Passover.”

Several recurring themes stand out:

- Jesus laughs at the other disciples’ worship and rituals, dismissing their understanding of God as misguided.

- A complex Gnostic cosmology unfolds — aeons, angelic rulers (archons), and a transcendent, unknowable God above the creator of this flawed material world.

- Judas alone grasps Jesus’ true identity and origin, recognizing him as coming from the “immortal realm.”

- In a key line, Jesus tells Judas that he will “sacrifice the man that clothes me,” suggesting a distinction between Jesus’ divine self and his human body.

The gospel ends abruptly with Judas handing Jesus over to the authorities — without any resurrection story, moral commentary, or explicit condemnation. This open ending made it easy for journalists and some scholars to cast Judas as an obedient instrument of salvation rather than a traitor.

Judas the “hero”? Gnosticism and early Christian diversity

In much of the 2006 coverage, Judas was presented as a tragic hero who does the dirty work Jesus needs done — freeing Christ’s divine self from the prison of flesh. National Geographic, CBS News, and several newspapers highlighted this angle, often with provocative headlines asking whether Judas had been misunderstood for 2,000 years.

This reading fits well with Sethian Gnostic theology. Many Gnostics believed salvation came through secret knowledge about the true, spiritual God and the way to escape the material cosmos. Jesus in the Gospel of Judas functions as a revealer of that hidden knowledge, and Judas as the disciple capable of receiving it.

Mainstream media often used this to underline how diverse early Christianity was. Writers in outlets like The New Yorker, TIME, and The New York Times explained that the text does not tell us what “really” happened in 30 CE, but reveals what some 2nd-century Christians thought about Jesus, Judas, and salvation.

The Gospel of Judas thus became a vivid illustration of a point made by historians such as Elaine Pagels and Bart Ehrman: that the early Jesus movement included many competing interpretations, only some of which became “orthodox.”

Media hype, mythmaking, and public reaction

The 2006 media wave framed the discovery in dramatic, sometimes breathless terms:

- The Los Angeles Times ran headlines like “Judas is no traitor in long-lost gospel” and explored how some modern Gnostics saw the text as spiritual affirmation.

- The Washington Post described Judas as the disciple who may have been “simply doing his master’s bidding,” while also noting that historians doubted the text’s historical value for reconstructing Jesus’ life.

- NPR segments and a PBS discussion introduced radio and TV audiences to a Judas who might be “Jesus’ best friend.”

- TIME magazine presented the gospel as part Da Vinci-Code-style thriller, part serious theological provocation.

Some religious commentators worried that this would unsettle ordinary believers. Others — especially scholars interviewed in mainstream outlets — emphasized that the text was written more than a century after Jesus and tells us far more about 2nd-century debates than about the historical Judas.

The authenticity question (and why most scholars moved on)

On one point, there was broad consensus very quickly: the manuscript itself is genuine. Laboratory tests by the University of Arizona dated the papyrus and leather to the 3rd–4th century, and ink analysis plus palaeography supported an ancient origin.

Major news stories in outlets such as the New York Times and Associated Press stressed that the debate was not about forgery but about historical and theological significance — “the real debate is whether the text says anything historically legitimate about Jesus and Judas.”

Most historians concluded it does not: it’s too late, too obviously shaped by Gnostic myth, and too isolated from earlier independent traditions. But it is invaluable as a witness to how some Christians re-imagined Judas to express their own understanding of salvation and divine knowledge.

Translation wars: is Judas a friend or a demon?

If authenticity was largely settled, translation was not. For a year or two, many media outlets repeated National Geographic’s initial interpretation: Judas as the one disciple who truly “gets” Jesus, obediently handing him over to fulfill a divine plan.

But by late 2007 a strong backlash emerged. Rice University scholar April D. DeConick argued in a widely cited New York Times op-ed, “Gospel Truth”, that key Coptic phrases had been mistranslated in ways that made Judas look better than he should. For example, she contended that:

- “thirteenth spirit” should be “thirteenth demon,”

- Judas is “set apart from the holy generation,” not “for” it, and

- he will not ascend to the holy generation.

If DeConick is right, the gospel still presents Judas as a uniquely important figure — but a sinister one, aligned with demonic powers rather than rehabilitated as a spiritual hero. Christian and secular outlets alike reported on this scholarly feud, with some characterizing the original project as an example of “scholarly malpractice” and media over-reach.

National Geographic’s scholars defended their work and pointed out that many of the disputed readings were discussed in the technical notes of the critical edition. Still, by 2008–2009, major coverage in venues like the Chronicle of Higher Education, the New York Review of Books, and follow-up pieces in newspapers treated the “good Judas” reading as at least highly contested, if not outright abandoned.

What the Gospel of Judas really changes

So, did the Gospel of Judas “rewrite” Christianity? The consensus in serious media coverage by 2009 was: no — but it does enrich the picture.

- It confirms early testimony (for example in Irenaeus’s Against Heresies) that some 2nd-century Christians revered a Gospel of Judas and held famously controversial views about his role.

- It illuminates Gnostic thought, showing how Jesus and Judas could be re-cast in a mythic drama about escaping the material cosmos through secret insight.

- It dramatizes the diversity of early Christianity, a point repeatedly emphasized in New York Times, New Yorker, Time and broadcast interviews with scholars such as Elaine Pagels and Bart Ehrman.

- But it does not overturn the historical picture of Judas derived from earlier, multiply attested sources (the four canonical gospels and early Christian tradition). Even sympathetic journalists underscored that a text written around 150–160 CE tells us more about that later era than about the original events.

In that sense, the Gospel of Judas is less a bombshell revelation than a fascinating case study in how scripture, heresy, media and marketing intersect. It shows how a fragmentary, esoteric 2nd-century text could, in the early 21st century, become a global story — shaped as much by modern anxieties and appetites for “secret” gospels as by anything Judas himself may have done.