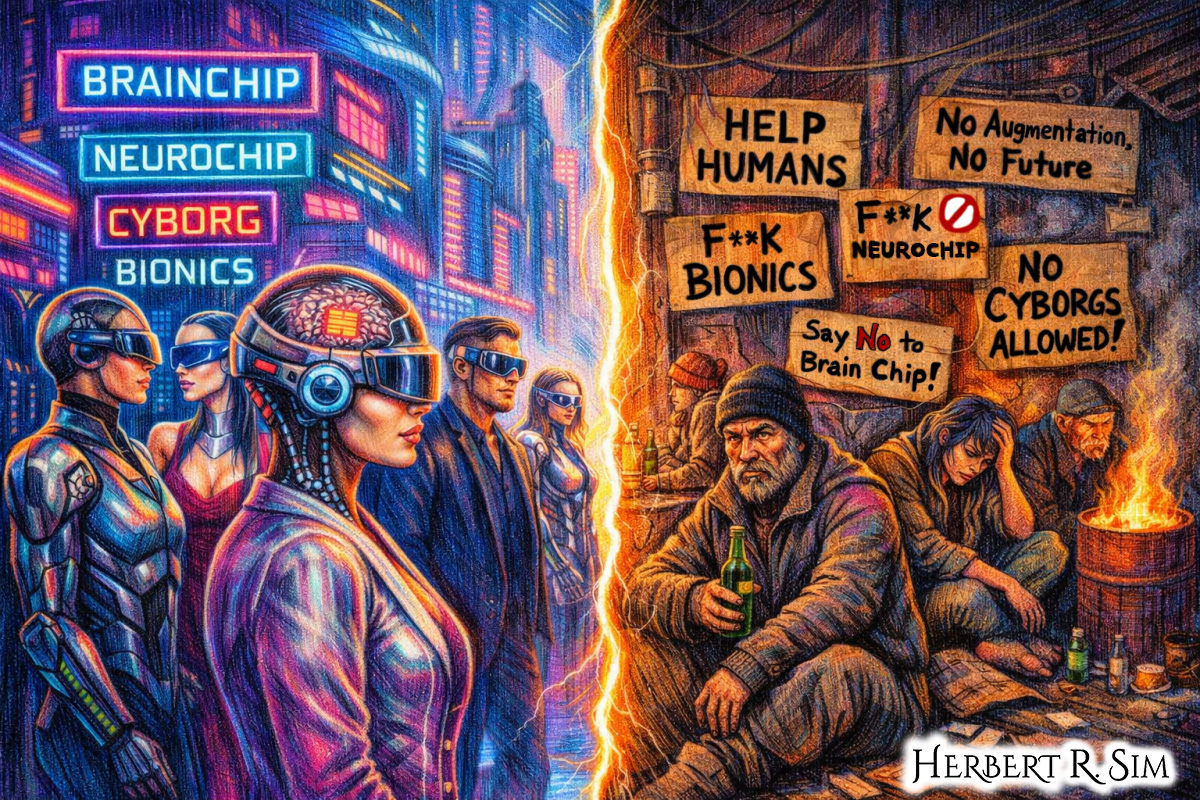

In my illustration above, I showcase the “Great Divide between Cyborgs & Humans”, the extreme wealth disparity gap.

The first generation of brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) and implantable “neurochips” is typically justified in therapeutic terms: enabling communication for people with paralysis, restoring function after stroke, and treating severe neurological or psychiatric disorders that resist medication. But history suggests that “restoration” is rarely the endpoint. Once a neural interface can reliably translate intention into action — typing, selecting, manipulating robotics — it becomes a platform for optimization: faster attention shifts, longer periods of focus, improved memory encoding, and tighter integration with computational tools.

In my earlier article entitled, “Without Equality, Human Enhancement Will Create a New Caste System”, the thesis was that uneven access to genetic editing and chimera-enabled medical breakthroughs could harden inequality into biology. The neurochip frontier risks a parallel outcome, but on a different axis: cognitive inequality — durable differences in attention, learning velocity, executive function, emotional regulation, and communicative throughput driven by unequal access to neurotechnology.

If the “augmented mind” becomes materially more productive, more resilient, and more legible to institutions, then the class divide stops being merely economic and becomes neurological.

1) The “therapy-to-enhancement” slide is built into the technology

BCIs were publicly demonstrated as life-changing assistive tools well before consumer hype caught up. A landmark example, widely reported in 2012, showed a paralyzed woman using an implanted interface to control a robotic arm to perform complex tasks — signaling the feasibility of direct neural control of external machinery. Once that pathway exists, it becomes a platform: first for restoring function, then for improving performance.

That platform logic accelerates when institutions invest at national scale. In 2013, the U.S. government publicly launched the BRAIN Initiative, explicitly aiming to develop tools to understand and manipulate neural circuits. Large public programs lower technical barriers and de-risk commercialization — often an early step toward uneven adoption.

2) The “cognitive premium” will track money, not need

Modern labor markets already convert cognitive advantages into earnings — through credentials, productivity metrics, and winner-take-most dynamics. Neurotechnology threatens to widen this gap because it can affect what employers value most: speed, focus, and output consistency.

Consider the plausibility of neuro-assisted productivity. Commentary in major outlets in 2014 described brain implants as a field in early stages — narrowly justified medically, not risk-free, and not yet “consumer.” That framing matters: it implies an early period in which access concentrates among those with premium healthcare, specialized clinics, and institutional sponsorship. In other words: the earliest cognitive advantages will accrue to people who are already advantaged.

Even non-invasive enhancement can skew toward elites. A prominent 2014 discussion in Scientific American noted strong public willingness to use brain-stimulation tools if they could improve school or work performance, indicating latent demand for “cognitive upgrades” outside medicine. Where demand meets high willingness-to-pay, stratification follows.

3) From “cursor control” to “enhanced cognition”: the capability roadmap

The most visible BCI stories focus on direct control — typing with thoughts, moving robotic limbs, or controlling avatars. In late 2014, The Verge described a BCI-mediated communication experience centered on typing via neural signals — an accessible illustration of how “mental intent” can become direct digital output.

But cognitive inequality is not primarily about novelty. It is about comparative advantage:

- Faster learning curves (shorter training time to competence)

- Greater attentional endurance (more productive hours)

- Higher decision accuracy under fatigue

- Enhanced human–machine coordination (better use of AI tools and robotics)

Research directions reported in 2014 emphasized implants intended to restore or strengthen memory in injured brains, effectively treating memory as an addressable engineering target. A Science report on DARPA’s funding push to “restore memories” framed implantable devices as a route to treat traumatic brain injuries — yet also raised skepticism and highlighted the ambition to engineer memory function. A contemporaneous Nature piece similarly covered implanted devices intended to restore memory, reflecting a mainstreaming of the “memory prosthesis” concept.

Once memory is treated as modifiable hardware/software, enhancement pressures follow: if a device can restore memory, it may also improve memory relative to baseline — at least in targeted tasks — and that is precisely the kind of marginal edge that reorders competition.

4) “Cyborg” workforces and the quiet coercion of augmentation

A frequent misconception is that enhancement will be an individual choice. In practice, work and institutions shape “choice” through incentives and norms. If a thought-controlled exoskeleton or prosthetic system becomes a productivity multiplier, employers can make augmentation structurally mandatory without ever mandating it explicitly.

This logic appeared in mainstream reporting about ambitious efforts to create thought-controlled exoskeletons, including the idea of demonstrating a brain-driven robotic suit at a major global event. Whether or not any single demonstration meets its promise, the direction is clear: neural control is being integrated into robotics, and robotics into human mobility — forming the “cyborg stack” of labor.

Similarly, The Verge described monkeys controlling a robot at great distance via neural signals — an early preview of remote physical labor mediated by brain signals. If such systems become reliable, they could reward a new elite skill: high-bandwidth neural control. That skill, in turn, will likely be trained and subsidized first in high-status environments (elite labs, military programs, top firms), not in the communities most exposed to economic displacement.

5) The consumerization problem: DIY neurotech and inequality-by-design

Not all cognitive augmentation requires surgery. Non-invasive tools — EEG headsets, neurofeedback, transcranial stimulation — already create a spectrum of “light enhancement.” A 2014 IEEE Spectrum piece highlighted how building mind-controlled gadgets became easier for DIYers, underscoring how neurotech can move from lab to garage.

Consumerization sounds democratizing, but it can still amplify inequality:

- Wealth buys better devices, coaching, data interpretation, and safer protocols

- Early adopters build skills that translate into career advantage

- Poorer users face higher risk of misuse, scams, and adverse outcomes

The risk intensifies when enhancement becomes a lifestyle marker. A 2014 Forbes trend piece explicitly flagged “brain computer interfaces” among disruptions to watch — evidence that the business imagination was already incorporating BCIs into broader commercial strategy.

6) Neurostimulation as a performance tool: militaries, schools, and “brain doping”

If cognitive upgrades work even modestly, the most aggressive adopters will not be consumers; they will be institutions with performance mandates: defense, intelligence, elite sports training, and competitive education.

In November 2014, The Guardian reported on experiments suggesting that electrical brain stimulation improved task performance more than caffeine and lasted longer — reported in the context of military-related attention-demanding work. This is a blueprint for cognitive inequality: organizations that can lawfully and systematically enhance performance for select roles will create internal and external hierarchies of capability.

Other coverage explored the emerging market boundary between science and consumer product. In early 2014, The Guardian discussed whether devices marketed toward gaming could really enhance performance — pointing to claims about reaction time, working memory, and learning speed while noting the limits of evidence. Even partial efficacy would matter in competitive systems, because advantage is relative: small gains repeated across years reshape trajectories.

7) The deepest inequality: control over mood, motivation, and mental suffering

Cognitive inequality is not only about IQ-like measures; it is about emotional regulation, resilience, and motivation — traits that power long-term achievement. Neuromodulation technologies aimed at depression and other disorders therefore have direct inequality implications.

A 2014 Reuters report on Brainsway described a magnetic stimulation “helmet” used for depression treatment and expansion efforts. A separate 2012 Reuters piece described ethics debates around “super-human” brain technology and the blurring of lines between humans and machines, including concerns about mind-controlled weaponry and enhanced concentration.

If affluent groups obtain better access to mood regulation and mental-health stabilization — whether via clinical devices or future implants — they gain not just comfort, but functional capacity: more stable careers, fewer disruptions, and better life planning. That is cognitive inequality in its most socially consequential form.

8) “Brain data” creates a surveillance class problem

Neurochips and BCIs don’t only output actions; they output signals — patterns potentially correlated with attention, fatigue, stress, and preference. That creates a second stratification axis: those who own and interpret neural data and those who merely produce it.

Early demonstrations of “brain-to-brain” communication — non-invasive, networked — show how neural signals can be transmitted across distance. IEEE Spectrum covered this as computer-mediated “telepathy,” emphasizing the interface model (record signals, transmit, stimulate) and thereby illustrating how neural states can become transferable information. In a commercial context, such signals could become a premium dataset — valuable for advertising, workforce monitoring, or behavioral prediction.

The inequality risk resembles earlier data economies, but worse: neural data is more intimate than clicks or location traces. If elites can buy privacy and control while others trade neural data for access or employment, a new “neuro-precariat” emerges — people whose cognitive privacy is continuously monetized.

9) Big neuroscience and the institutional advantage loop

Large brain projects also shape inequality by controlling the innovation pipeline. In 2013, TIME and other outlets described the Obama-era push to invest in brain mapping tools, drawing analogies to the Human Genome Project. The Atlantic asked why society should spend billions to map the brain — capturing how quickly brain science became a prestige-scale project.

Parallel mega-projects can concentrate power. WIRED reported on Europe’s €1 billion Human Brain Project and the ambition to simulate brain function on supercomputers — an approach that, whatever its scientific fate, signals the scale of capital and institutional influence converging on cognition. Vanity Fair’s framing of “brain mapping” as a high-profile public initiative underscores how such programs can become politically and culturally legitimized even when goals remain broad.

In inequality terms, “big neuroscience” tends to benefit those positioned to capture downstream applications: advanced hospitals, elite universities, defense contractors, and large tech/biomed firms.

10) What a “cognitive caste system” would look like in practice

A cognitive caste system does not require overt laws. It emerges when:

- Augmented people are systematically more productive, credentialed, and resilient

- Institutions quietly prefer augmented profiles (lower training cost, higher output)

- Non-augmented people are framed as choosing to fall behind

- Neural data ownership and neuro-access become correlated with class

The path is incremental: first medical, then elective, then expected. As The Guardian noted in 2014 in its general explainer tone, many questions remain about how and why stimulation works — yet the social pull toward advantage is constant. And once cognitive enhancement becomes a positional good, egalitarian values alone will not prevent stratification; governance must be explicit.

11) Reducing inequality before it becomes biology

If societies want neurotechnology without neuro-feudalism, they will need:

- Clear separation between therapeutic access and elective enhancement markets (or explicit policy for both)

- Anti-discrimination protections for augmentation status

- Rules limiting workplace coercion and neural surveillance

- Public provisioning for clinically necessary neurotech (so function is not paywalled)

- Strong constraints on neural data extraction, resale, and behavioral inference

Cognitive inequality is not inevitable. But without deliberate policy, it is the default outcome of expensive, performance-relevant technology.