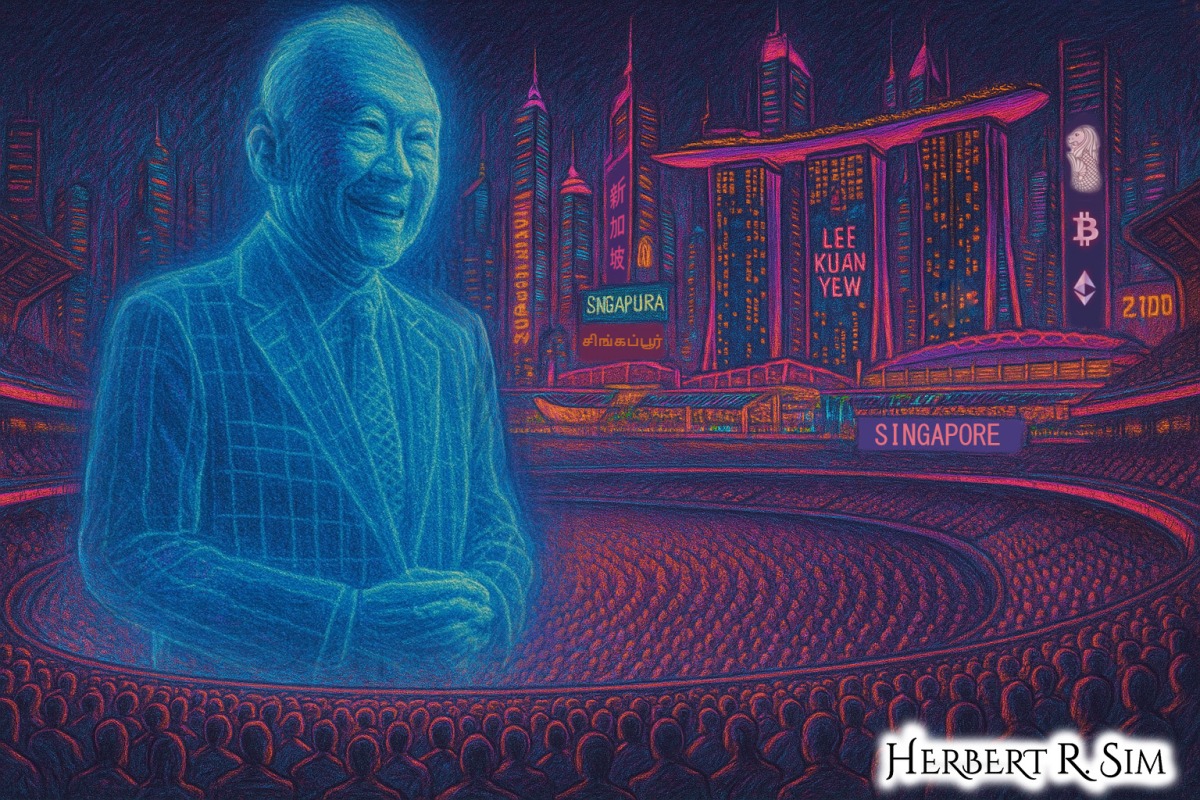

In my illustration above, featuring a futuristic stadium filled with people, watching a hologram of the founding father of Singapore – ‘Lee Kuan Yew‘ speaking to them. This art is an homage to the late leader of Singapore.

In a sense, you already have a legacy online. Your social-media posts, old chat logs, voice messages, cloud-photos, even your YouTube comments form a faint record of you. In the next few decades, your digital self may become far more than a static archive — it may become an interactive presence, a “digital ancestor” aka “Deadbot” that future children and grandchildren meet, converse with, consult, or reuse. This article explores how that might work, how it will feel, and what choices you can make now to shape it.

From static memorials to dynamic digital selves

For many years the question has been: when you die, what happens to your Facebook page, your email account, your cloud-storage full of photos? The Economist has documented how “everyone leaves digital traces behind when they die — either deliberately in the form of social-media profiles and posts, or incidentally, with… data.”

A growing body of commentary points to how this is no longer just digital clutter but the beginning of a new kind of afterlife — one that uses AI, voice cloning, avatars and chat interfaces to keep you more present. A guardian-style article described how “digital recreations of dead people need urgent regulation” because the technology is becoming feasible and the psychological implications uncertain.

Academic research likewise is examining what they call “AI afterlife” or “digital legacy agents” — avatars created from your digital data that family may interact with after you’re gone.

Thus the trajectory: from legacy contacts and memorial pages to chatty, voice-enabled, avatar-enabled digital selves.

How your descendants might “meet” you

Imagine your great-grandchild in 2070 or 2080. They don’t just look at a photo of you — they interact with a digital version.

1. The archive mode

First stage: a searchable, browsable archive of your digital life. They might open an app, ask “Tell me about my great-grandma’s university days,” and the system pulls together photos, voice memos, blog entries, maybe YouTube clips, preserved and indexed. Families already treat digital accounts and cloud vaults as part of estate-planning. This creates the basis for a deeper presence.

2. The conversational mode

Next: a more interactive version of you — a chatbot or voice agent built from your texts, emails, social-media posts, recordings, and perhaps video. These “digital ancestors” might answer questions like:

- “How did you deal with your first job?”

- “What did you think about climate change in the 2020s?”

- “What advice do you have about marriage/kids/career?”

Such systems already exist in rudimentary form. One article described how AI ‘deathbots’ are built from voice recordings, social-media posts and emails to simulate the voice and personality of someone who died.

Another piece described how your “digital shadow” — emails, voice notes, metadata — is increasingly activated by AI to provide continuity of relationship rather than simply a memorial.

This mode may blur the lines between archive and conversation — so the digital you isn’t just something they look at, but something they ask.

3. The embodied/visceral mode

Beyond chat: imagine a hologram, an augmented-reality avatar, or a VR presence of you at family gatherings. The technology for creating life-like digital versions of people is advancing. A Singapore-based opinion piece warned how “AI chatbots and virtual avatars to holograms… technology offers a strange blend of comfort and disruption”.

In that scenario, your great-grandchild might invite your avatar to join the dinner table via AR glasses, ask you a question and see your “face” animate, your voice reply, and maybe your presence fade afterwards.

In effect: your digital self becomes part of the family ritual, not just a memory.

Emotional and social implications

What will this mean for your descendants, emotionally and socially?

- Continuing bonds: Many psychologists describe grief not as detachment but as continuation of a relationship with the deceased. A digital presence could extend that bond.

- Blurred boundaries: But if the digital you is conversational, children might struggle to differentiate between “real you” and “digital you.” That could affect how they process loss. The Guardian warned that interactive avatars might hinder letting go.

- Memory distortion: Because AI may generate responses you never actually said, future generations might attribute things to you that you never meant, or forget that they’re dealing with an AI replica. A Time article on “digital resurrection” pointed out how this might implant false memories.

- Family dynamics: Who gets to control your digital presence? If your avatar is still active decades later, conflicts may arise: Should it remain available? Edited? Retired? If the digital you gives advice that some family disagree with, who moderates?

- Inequality and access: Technology-driven “digital afterlifes” may cost money or require privileged data to build. One article warned of a widening gap: while anyone can leave photos, only some may get interactive avatars.

Agency, consent, and legacy planning

Given how your digital self might live on, how do you shape it?

Make your intentions clear

Consider whether you want your digital self to be interactive, conversational, or simply archived. Some companies now advertise “digital immortality” services.

If you want your descendants to meet you, decide what form that takes: text-only, voice-enabled, avatar, hologram.

Curate your digital assets

Rather than leave everything, think about what you want preserved: key stories, voice recordings, old videos. An article in The Guardian recommended drawing up a “digital executor” and inventory of your online life.

Quality over quantity will help — because future systems may filter or index your material.

Consider ethical boundaries

If you create an interactive digital version, what safeguards should apply? The Cambridge researchers urged regulation: “services should limit interactive features to adults…, should be transparent, and include a retiring mechanism.”

Decide if you want your avatar turned off after a set time, or flagged as “archived” rather than “live.”

Acknowledge the limitation: “You” won’t really be you

Even the best AI replica is a simulation based on data. You’re not just your texts or photos. Academic work on “digital me ontology” argues that such agents are not the real individual, but a constructed artefact.

It’s helpful for your descendants to know that the avatar is a tool for memory, not a resurrection.

The peek into future family gatherings

Imagine a family reunion in 2050 or 2070. The room fills with laughter, kids, and smartphones. In one corner, your great-granddaughter asks her phone: “Grandpa, what happened on your first job at the bank?” Instantly the screen plays a 3-minute personalised answer recorded by your avatar: your voice, your war-story about how you messed up payroll and learned leadership.

Later, at dinner, your great-grandson puts on AR goggles; via an app he asks you what you thought of the moon landings. Your hologram appears next to his plate, animated and responsive. Afterwards he toggles a “legacy archive” mode and reviews you in “raw” form — unedited voice messages you left, critical reflections you once made, old blog posts you wrote in your 30s. He sees some you had hidden from the family, giving him a richer sense of you — and a more complex sense of who you were.

In a darker moment, a cousin unplugs your avatar after seeing it repeatedly give career advice nobody asked for, and they debate whether to retire the “digital you” before it becomes a distraction rather than gift.

Either way, you don’t disappear. You persist as digital presence, curated, interacted with, perhaps loved, perhaps archived — your descendants meeting you in ways we’re only just beginning to imagine.

Final thoughts

Your digital legacy is no longer just links and passwords. It may become a living interface that future generations treat as part of the family landscape — an active presence, not just a memory. That means you have a choice: you can let the technology carry on whatever remains happen to persist, or you can design your digital after-life with intention.

By thinking ahead — about what you want preserved, how it will be used, by whom and for how long — you give your children and grandchildren not just a memory of you, but a meaningful bridge across generations. The future may well see them meeting you online. And when they do, let it be you.