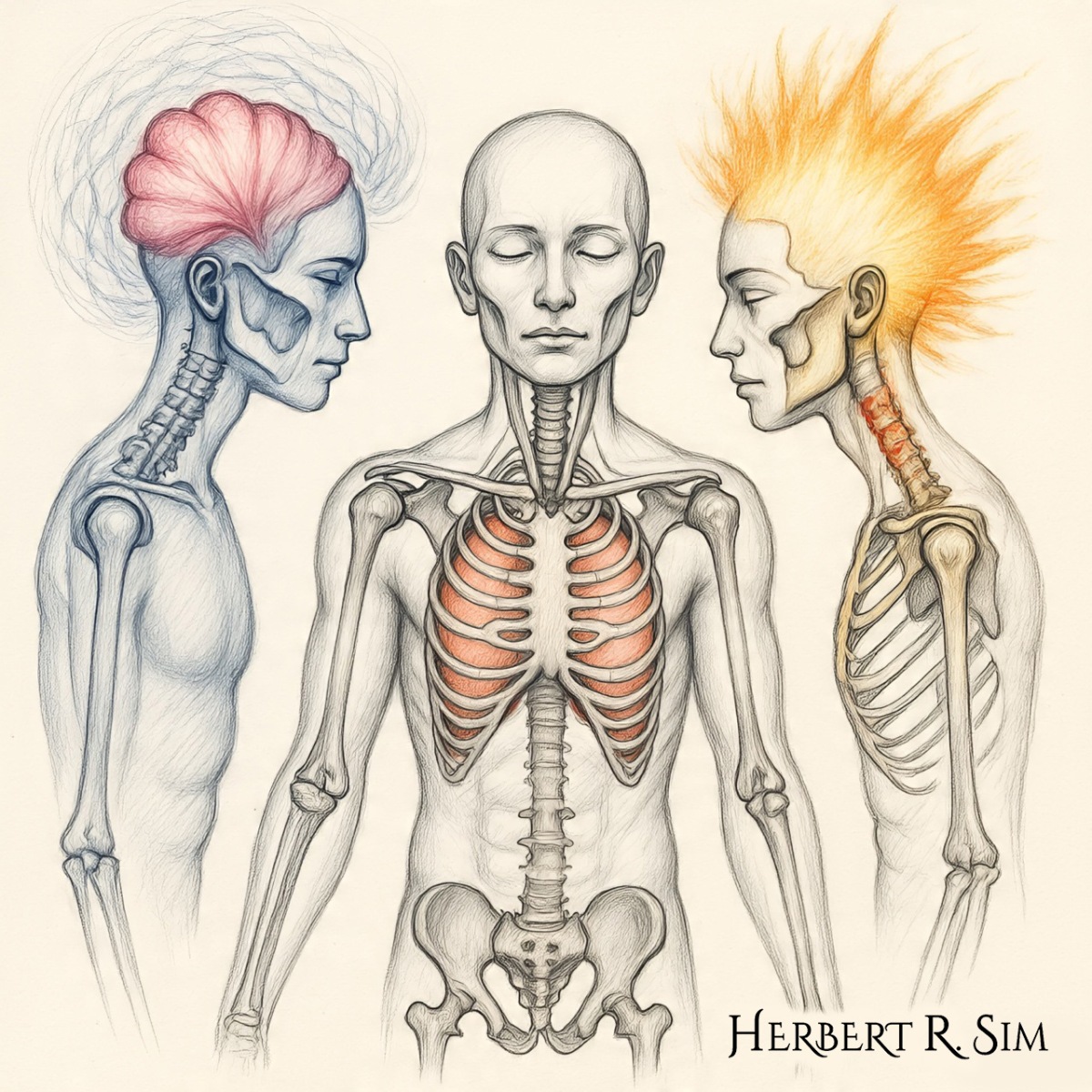

I was pondering about human cloning, and about what separates a clone from the original. It is the soul and the spirit. Next, what defines a soul and a spirit?

Within Protestant Christians — body, soul, and spirit are not throwaway synonyms. They are different lenses for understanding what it means to be human before God: our physical life (body), our inner self/personhood (soul), and our God-oriented capacity for relationship with him (spirit). At the same time, Scripture insists we are a unified whole, not a set of detachable parts. Holding both truths together keeps Christian teaching balanced.

Bible foundations: unity and distinction

Genesis says God formed humankind from the dust and breathed life into us — material and immaterial in one living person. Later, Paul prays that believers be kept blameless in “spirit and soul and body,” a line often cited to show there can be meaningful distinctions within our one human nature.

Two classic Protestant models: dichotomy and trichotomy

Protestant theologians have long discussed whether humans are fundamentally two-part (body + soul/spirit; “dichotomy”) or three-part (body + soul + spirit; “trichotomy”). Many evangelical writers note that Scripture sometimes speaks in two-part and sometimes in three-part terms, cautioning against building a rigid system. A widely used seminary outline from 2005 summarizes the debate and urges keeping the Bible’s emphasis on unity.

What “soul” usually means in Scripture

Biblically, soul (Heb. nephesh, Gk. psychē) often points to the whole self as a living person — our inner life with thoughts, loves, desires, and moral center. Jesus warns of those who can kill the body but cannot kill the soul, highlighting the soul’s enduring significance beyond bodily death.

What “spirit” usually means in Scripture

Spirit (Heb. ruach, Gk. pneuma) frequently signals our God-ward capacity: the dimension by which we know, worship, and are enlivened by God’s Holy Spirit. Hebrews says God’s word discerns “the division of soul and spirit,” language that doesn’t split a person into separable bits but recognizes meaningful distinctions in the one person’s inner life.

The body — created good and destined for resurrection

The human body is not a disposable shell but part of God’s good design. Sin brings bodily death, yet the gospel promises resurrection: the Spirit who raised Jesus will give life to our mortal bodies. Protestant preaching has repeatedly urged hope not only for “souls” but for whole-person resurrection.

A Protestant caution against over-systematizing

Evangelical commentators often warn that 1 Thessalonians 5:23 isn’t a schematic of human parts but a rhetorical way to say “your whole self.” Classic Protestant expositors therefore read such texts as guarding comprehensive sanctification, not mandating a philosophical anatomy.

Lived discipleship: loving God with all you are

To love the Lord “with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength” is to give God your entire person — affections, intellect, will, and physical strength. Protestant teachers have pressed this into daily obedience: present your bodies as living sacrifices while being renewed inwardly by the Spirit.

Why this matters for ethics and mission

A whole-person gospel resists two distortions: bodily neglect (treating faith as purely inward) and soulless activism (treating people as only bodies or only brains). Historic Protestant voices have tied spiritual renewal to embodied justice and neighbor-love — piety that involves hands and hearts.

Perspectives from evangelical scholarship

Protestant study resources written for pastors and students before 2009 note that Paul can use “body” to mean the whole person, and they stress that the Bible’s big story treats humans as unified image-bearers who nevertheless have an inner‐outer distinction. That balanced reading steers between both reductionism (we’re “only bodies”) and speculation (over-neat inner partitions).

Guardrails from Reformed teachers

Within conservative Protestantism, Reformed writers often favor dichotomy (body + soul/spirit) while insisting the unity of the person is primary. Foundational outlines and catechetical materials used in churches and schools prior to 2009 lay out the options and commend charitable restraint in labeling others.

Spiritual formation is whole-life formation

Evangelical pastors repeatedly taught in the 2000s that Christian “spiritual formation” isn’t a disembodied hobby; it is the Spirit reshaping habits, desires, and relationships. Christianity Today’s pre-2009 essays, for example, connected spiritual gifts, friendships, and vocation to the Spirit’s work in our actual bodies and communities.

Wrestling with doubt and the “dark night” in Protestant experience

Protestant writers have also engaged the language of the “dark night of the soul” — the felt absence of God — as part of normal Christian experience. Reporting and commentary prior to 2009 treated such seasons as occasions for deeper trust rather than signs that “the soul” is unreal or unimportant.

Engaging modern culture without surrendering core claims

Mainstream outlets in the 2000s reported neuroscience’s challenge to the immortal soul, while also noting philosophers who argued consciousness might transcend mere brain function. Protestants read such debates alongside Scripture’s insistence that human life is more than material — yet never less than embodied.

The Spirit’s renewing work in everyday life

Romans 8 grounds Christian hope squarely in the Holy Spirit: those united to Christ are indwelt, empowered, and led by him, even as our bodies still experience weakness and decay. Protestant preaching before 2009 emphasized this tension — already made alive in the inner person, not yet freed from bodily frailty — until resurrection day.

Soul care and social life

Because humans are body–soul–spirit creatures, Protestant ethics joins soul care (prayer, Scripture, worship) with social responsibility (mercy, truth, justice). Evangelical journalists and analysts before 2009 regularly explored how belief shapes public life, implying that spiritual convictions are never merely private.

The language of “soul” in public square writing

Even secular coverage in the late 2000s reached for “soul” language — of nations, movements, art — because it names something deep and identity-level. Christians can accept that metaphor while insisting the human soul is real, accountable to God, and destined for resurrection in Christ.

Protestant distinctives without a Catholic angle

Without invoking Catholic distinctives, Protestants have emphasized Scripture alone as the norm, read in the communion of the church, to shape our anthropology: we are embodied image-bearers (Genesis 2), with a soul accountable beyond death (Matthew 10), and a spirit that the Holy Spirit makes alive (Romans 8). That triad keeps Christian life concrete, hopeful, and God-centered.

Practical implications for discipleship

- Worship: Offer your body in gathered praise; engage your mind in truth; open your spirit to the Spirit’s leading.

- Ethics: Guard what forms your inner life (soul) and what you do with your bodily life, since both belong to Christ.

- Hope: Expect bodily resurrection and soul rest with Christ even as you pursue Spirit-led sanctification now.