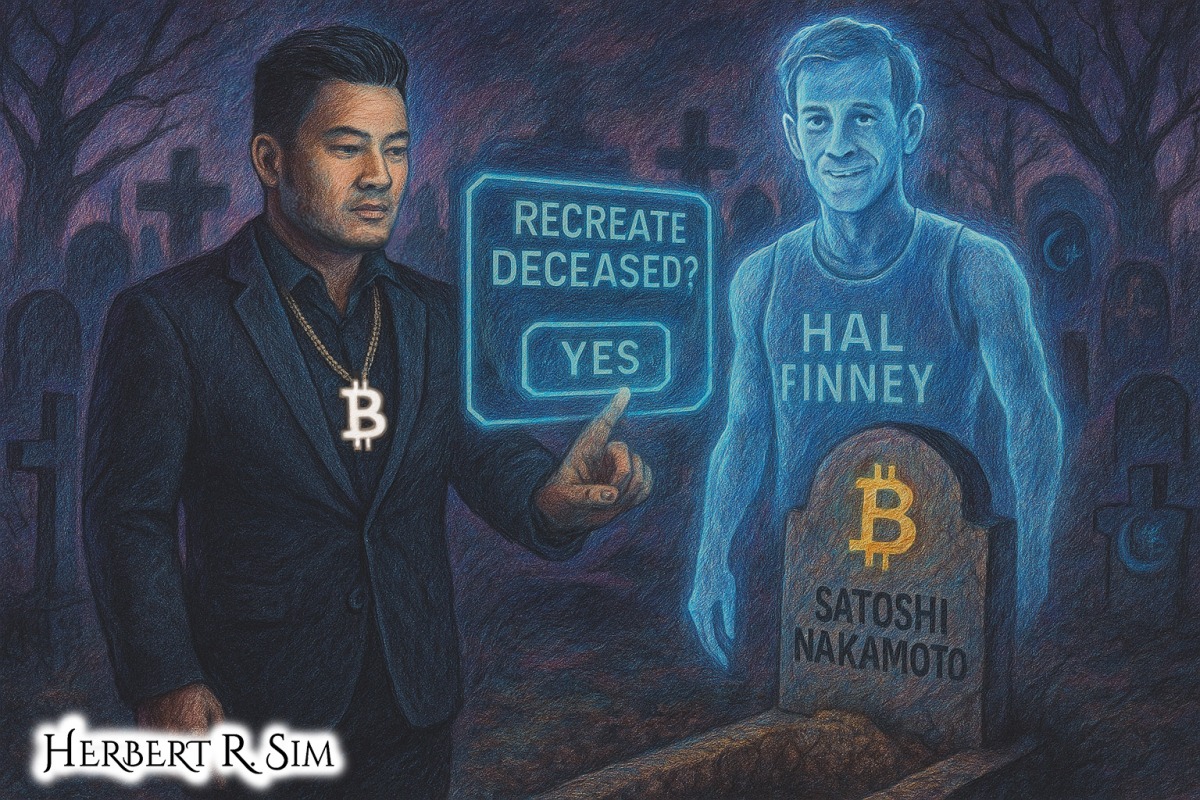

In my illustration above, I feature a computer terminal With the question: “Recreate Deceased?” towards the revival of Satoshi Nakamoto from the ‘grave of anonymity’. The illustration pays homage to the late Hal Finney (1956 – 2014), suspected to possibly be the legendary ‘founder/creator of Bitcoin‘ himself.

“Digital resurrection” sounds like science fiction: chatbots that talk like the dead, hologram concerts starring long-gone singers, or “interactive” videos that answer your questions in a late relative’s voice. But these ideas are already here, woven through everything from memorial apps and legacy settings on social media to experimental AI griefbots and dead-celebrity tours.

As the tools get more powerful, the question shifts from can we to should we. Three moral knots keep coming up: consent, psychological impact, and authenticity.

1. From memorial pages to talking with the dead

The earliest “digital afterlife” debates focused on mundane things: who gets access to your email, social media, and photos when you die. News features about “Facebook for the dead”, Google’s inactive-account manager, and digital-asset laws treated death as a data-management problem: passwords, ownership, and inheritance.

Very quickly, though, memorials stopped being static. Social platforms introduced memorialization tools, legacy contacts, and policies about what happens to your profiles after death, turning timelines into lasting, searchable shrines that can surface unexpectedly in “memories” feeds.

Then came attempts to simulate the person, not just preserve their posts. One of the most famous cases was Roman Mazurenko, a young man whose friend built a chatbot from his text messages so people could keep “talking” to him after he died. Journalists described friends treating the bot like an ongoing conversation with Roman, blurring the line between mourning and maintaining the relationship.

At the same time, entertainment industries started experimenting with digital resurrections at scale. Hologram tours bring back Tupac, Maria Callas, Roy Orbison and other stars, promising “new” performances from artists who have been dead for years. Business coverage frames this as a booming market for posthumous shows and “digital embalmers” who protect and monetize virtual likenesses.

So digital resurrection isn’t one technology; it’s a spectrum — from memorial pages to AI griefbots to hologram icons — and each point on that spectrum raises a slightly different ethical question.

2. Consent: who gets to decide on a second life?

The most obvious dilemma is consent. Most people who die today never explicitly agreed to be turned into a chatbot, a voice clone, or a strolling hologram. Yet companies already pitch families and estates on ways to keep the dead “active”: interactive video interviews captured before death, digital personas built from social media, or branded virtual appearances.

Even where there are legal arrangements — wills, digital-asset clauses, or posthumous publicity rights — it’s not clear they cover emotional uses like griefbots. Guidance about planning your “digital afterlife” tends to focus on giving someone access or shutting accounts down, not approving a realistic simulation of your personality for decades to come.

With celebrities, money and power complicate things further. Dead-celebrity hologram tours often rely on deals with estates or rights-holders rather than the person’s own clearly expressed wishes. Media coverage of Hendrix, Sinatra, Tupac and others repeatedly circles the same question: when an estate signs off on a digital resurrection, is that morally enough, or are we overriding what the person might reasonably have wanted in life?

Consent also matters for the living. When you build a griefbot from someone’s chat history, you’re almost always feeding in conversations that involve other people, who never agreed to have their words repurposed into training data for a quasi-person. Friends of Mazurenko, for example, had their own messages pulled into an AI that now imitates him, raising hard questions about shared privacy and joint ownership of digital traces.

A defensible ethical baseline would treat digital resurrection as opt-in only: no one becomes a bot or a hologram unless they explicitly said yes, in a context where they understood the likely uses and limits. But the reality so far is mostly ad hoc: tech first, ethics later.

3. Psychological impact: comfort, dependence, or harm?

Digital resurrection technologies are often marketed as therapeutic: a way to ease grief, maintain “continuing bonds,” and say what you never got to say in life. Stories about griefbots and memorial services note that some bereaved people find comfort in sending final messages, revisiting archived conversations, or even watching an interactive recording of a loved one answering their questions.

But psychologists warn that grief is not just missing someone; it’s also the slow, painful work of accepting that they are gone. If a chatbot is always available, if a hologram keeps touring, if a digital avatar keeps posting on your behalf, the loss might never fully settle. Media commentary on AI “ghosts” and digital immortality repeatedly worries that these tools could entrench denial, prolonging distress rather than resolving it.

There are subtler harms too:

- Role confusion: Is the bot your friend, your diary, a product, or a service subscribed to by thousands of other people? People interacting with memorial chatbots sometimes report a strange tension between feeling genuine affection and knowing, intellectually, that they’re talking to code.

- Emotional dependence: If the easiest source of comfort is a 24/7 bot that always responds “in character,” it might discourage seeking support from humans or from traditional rituals, which offer community and shared meaning.

- Unexpected triggers: Social-media “memories”, algorithmic resurfacing of old photos, or synthetic performances of a dead artist can ambush people with grief in public or commercial contexts they didn’t choose. Reports on memorialized accounts and hologram concerts highlight how jolting this can feel.

For some, these tools will genuinely help — especially when co-designed with therapists, used for short periods, or framed clearly as symbolic. For others, they may deepen loneliness or blur reality at exactly the moment when clarity about death is psychologically crucial.

4. Authenticity: are we preserving people or rewriting them?

Even if consent and mental health risks were solved, there’s an uncomfortable question: what are we actually bringing back?

Digital remains are selective and biased. A person’s social media, emails, texts, or recorded interviews reflect particular moods, relationships, and stages of life. When a company assembles these into a single, polished bot or avatar, it produces a version of the person that may be more marketable, more pleasant, or more brand-aligned than they ever were in real life. Coverage of “digital embalmers” and estate-run accounts shows how carefully curated these personas can be.

This is especially problematic for historical trauma. Projects that create interactive testimonies of Holocaust survivors, for example, aim to preserve memory and educate future generations. Yet they also raise the worry that heavily scripted, AI-mediated encounters could gradually replace messy, archival history with smoother, more palatable narratives.

Entertainment pushes authenticity even further. Hologram tours restage artists in ways that may never have happened — new arrangements, different venues, mash-ups with living performers. Critics note that “Frank Sinatra” or “Jimi Hendrix” on stage today is partly an aesthetic choice by producers and partly a legal construction by estates and rights-holders. The same brand logic could one day rewrite controversial public figures to make them more sellable.

From an ethical standpoint, authenticity demands at least three things:

- Transparency: No pretending the simulation is the person; it should be clearly labeled, with guardrails around how it can speak or act.

- Fidelity to context: Avoid making the dead endorse products, causes, or viewpoints they never supported.

- Archival honesty: Preserve access to original materials and biographies so that future viewers can see how a digital persona was constructed, not just consume the polished result.

Without those, digital resurrection risks turning real humans into endlessly editable intellectual property.

5. Inequality, commodification, and cultural impact

Digital resurrection isn’t just personal; it has social and economic dimensions.

First, it’s unequally distributed. High-end services — including hologram shows, bespoke interactive recordings, or meticulously managed “posthumous brands” — are mostly available to celebrities and the wealthy. Reports from business and culture magazines show a growing industry around extending the earning power of famous names long after death.

Meanwhile, ordinary people rely on whatever tools big tech platforms decide to offer: memorialization checkboxes, legacy contacts, and terms of service that can change at any time. For many, the main question becomes not “how do I live forever?” but “how do I keep my loved one from being turned into something they wouldn’t recognize?”

Second, there’s a risk of commodifying grief. When a hologram tour or griefbot subscription depends on recurring payments, your ongoing relationship with the dead is partly gated by your ability to keep paying. Fiction like the series Upload satirizes this dynamic: luxurious digital afterlives for those who can afford it, cheaper glitchy options for everyone else. Interviews and promotional pieces about the show underline how close this feels to real-world business models.

Finally, digital resurrection shapes how we, as a culture, think about mortality. Earlier essays on “Facebook for the dead,” e-tombs and “digital immortality” worried that if everything can be endlessly preserved and replayed, death might seem less final, but also less meaningful. We may shift from remembering people as finite, embodied beings to treating them as ongoing streams of content that can always be updated, remixed, or re-licensed.

6. So… should we do it? Some ethical guardrails

There’s no single answer to “Should we recreate the dead?” The ethics depend on how, why, and for whom. But media debates and early experiences suggest some concrete guardrails:

- Explicit, informed opt-in

- Treat digital resurrection like organ donation or advanced directives: something people must choose in life.

- Separate consent for different uses: private family grief tools, public educational projects, and commercial entertainment should each require their own permissions.

- Respect for the bereaved

- Design with mental-health experts to reduce the risk of complicated grief.

- Build in off-ramps: options to pause or retire a bot or avatar, and to delete data completely.

- Strong authenticity norms

- Label simulations clearly and avoid using them to make new political statements, endorsements, or apologies that the person never made.

- Keep robust archives and document how the digital persona was constructed.

- Legal rights after death

- Update estate and digital-asset law so that people can control not just data access, but also whether their likeness and voice can be synthesized and monetized.

- Equity and cultural sensitivity

- Guard against a world where only the famous and wealthy get carefully curated digital lives, while everyone else’s data is strip-mined into generic training sets.

- Recognize cultural and religious traditions that view disturbing the dead — even digitally — as deeply wrong, and carve out space for a “right to be left dead”.

Used carefully, some forms of digital continuation — archived messages, one-time interactive interviews, thoughtfully designed memorials — may help people grieve and remember. Pushed too far, especially by commercial incentives, digital resurrection risks violating consent, warping memories, and turning both the dead and the living into raw material for endless content.

The unsettling truth is that death gives life its shape. Technologies that try to erase that boundary may offer comfort, but they also demand humility. The most ethical stance may not be to resurrect as much as possible, but to choose — carefully and sparingly — when a fragmentary digital echo serves love and memory, and when the most humane thing is to let the dead rest.