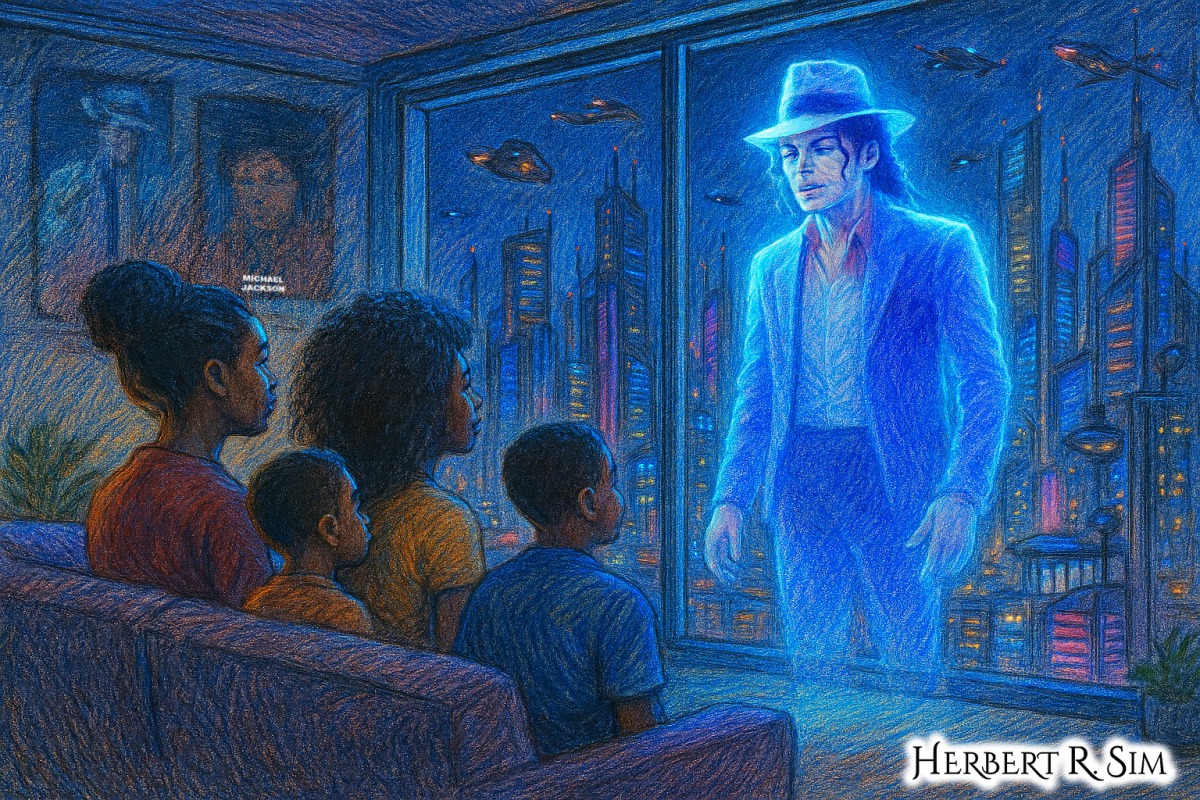

My illustration above showcasing the descendants, family members of late pop legend Michael Jackson (1958-2009), engaging with his holographic artificial intelligence digital twin of him.

Your online presence will probably outlive you, which I covered in my earlier article entitled: “From Flesh to Code: Embarking on the Quest for Eternal Life” about ‘Digital Immortality’.

Photos, DMs, playlists, emails, subscription logins, biometric scans… all of that becomes a kind of digital estate that someone has to deal with — or that simply hangs around the internet like a ghost.

This article looks at four big questions:

- Who inherits your Instagram (and other social media)?

- What happens to your subscriptions and digital purchases?

- How “digital ghosts” keep showing up after we’re gone.

- Who inherits your face — and what about deepfakes and AI clones?

1. Who inherits your Instagram? (And Facebook, Google, etc.)

Social platforms were built for the living, but they’ve gradually had to invent a “death UX.”

Facebook: memorial pages and legacy contacts

Facebook originally just deleted profiles of dead users, then shifted to “memorial pages” after several high-profile tragedies. Memorialized accounts stay online, but can’t be logged into; friends can keep posting memories, but the profile is frozen.

In 2015, Facebook added the “legacy contact” feature: you can designate someone to manage parts of your account after you die — pin a final post, change your profile picture, accept friend requests — but not read your messages.

Despite this, legal battles still happen. In 2017, a German court case saw parents lose an appeal to access their deceased daughter’s Facebook account, even though they argued it should be treated like a diary. The court prioritized privacy and communications secrecy over inheritance.

Google: Inactive Account Manager

Google took a more “estate-planning” approach with Inactive Account Manager. You pick a period of inactivity (for example, 6 or 12 months). If you don’t sign in and don’t respond to alerts, Google can either delete your data or share it with trusted contacts you named.

This can cover Gmail, Google Drive, YouTube, Photos, and more — effectively a large chunk of your digital life. Commentators at the time argued that, creepy name aside, it was one of the first serious tools for a “digital will” built straight into a major tech platform.

Instagram & others

Instagram, like Facebook, offers memorialization or removal of accounts, but generally won’t give out passwords or private messages; access typically requires a court order and even then is limited. Most major platforms now have some form of:

- Deletion (close the account entirely)

- Memorialization (keep it as a static tribute)

- Limited control by a nominated contact

But almost all of them assume you made those choices while alive. If you didn’t, your family is often stuck navigating a mess of support forms, death certificates, and unclear policies. Many writers and researchers now recommend that people explicitly document who should manage their accounts and how.

2. What happens to your subscriptions and digital purchases?

Your “digital stuff” may feel like property, but legally it often isn’t.

You don’t really own that iTunes library

When a story circulated about Bruce Willis wanting to sue Apple over whether his iTunes music could be left to his children, it sparked a broader conversation about digital ownership. Outlets quickly pointed out: under most terms of service, you’re buying a non-transferable license, not a physical asset.

A MarketWatch column bluntly asked: “Who inherits your iTunes library?” and concluded that, legally, the answer is often “no one” — the license dies with you. Legal blogs and commentators extended that logic to e-books and app stores: unlike CDs or paper books, your Kindle or iTunes collections usually can’t be formally bequeathed.

Streaming killed the inheritable library

On top of license issues, streaming has replaced downloads in music, film and TV. Commentators described Apple’s move into streaming as “the day the download died”, marking a shift from owning files to renting access.

For your heirs, that means:

- Your Spotify / Netflix / Apple Music libraries are just curated access, not assets.

- If no one has your login, your carefully curated playlists and watchlists simply vanish when billing stops or the account is closed.

Digital estate planning: more than passwords

Wealth-management and estate-planning writers increasingly warn that digital assets are a blind spot: everything from domain names and crypto wallets to online businesses and social media accounts.

Practical steps they recommend include:

- Listing important online accounts (banking, subscriptions, cloud services).

- Storing passwords in a secure manager and giving a trusted person access instructions.

- Clarifying in your will who should control business accounts, websites, and monetized channels.

- Deciding which recurring subscriptions should keep running (e.g. for an online business) and which should be cancelled immediately.

Without that, families are left chasing mysterious credit-card charges, locked out of key platforms, or discovering only later that a vital service was tied to a dead person’s email.

3. Digital ghosts: when your data lives forever

Even if nobody logs into your accounts, your data can keep “speaking” after you die.

Social feeds as memorials

Researchers and journalists have described how social networks quietly turn into cemeteries of profiles. One Atlantic piece showed that when someone dies, their Facebook friends tend to interact more, and those strengthened ties can last for years.

Other writers have talked about the emotional weight of digital remains: thousands of uncurated photos, old status updates, and endless email threads that heirs might inherit — or feel guilty deleting.

A Guardian feature on “web immortality” highlighted services that schedule messages to be posted after your death or keep posting on your behalf, effectively extending your online presence indefinitely.

The platform problem: birthdays, memories, and “On This Day”

Platforms are optimized to keep engagement up, not to handle grief. Scholars studying “Death and the Internet” have noted the painful side-effects: birthday reminders for people who are gone, “On This Day” resurfacing posts with the deceased, and algorithmic friend suggestions involving dead users.

Without careful settings or deletion, you end up with:

- Ghost notifications (reminders tied to accounts that no one controls)

- Algorithmic haunting (old photos and posts resurfacing unexpectedly)

- Confusion about who should have the right to shut things down

And because many platforms claim ownership or broad use rights over user-generated content, families can’t always insist on removal — especially if they don’t have login credentials.

4. Who inherits your face? Deepfakes, AI and post-mortem identity

Your most powerful “digital asset” may not be your posts or playlists — it’s your biometric data: your face, voice, and other uniquely identifying traits.

From playful filters to deepfake porn

By 2018, journalists were already warning about deepfakes: AI-generated videos that can convincingly swap one person’s face into another scene. Wired described how the same machine-learning techniques driving image recognition were being used to generate highly realistic fake videos.

Tech reporters at The Verge documented how enthusiasts on Reddit used these tools to create fake celebrity porn and swap actors’ faces into blockbuster movies — for example, replacing an actor in a Star Wars film with Harrison Ford’s younger face.

All of this showed that once enough photos and video of you exist online (which is true for most people on social media), your likeness can be:

- Cloned into new contexts you never approved.

- Combined with synthetic audio to make you “say” things you never said.

- Reused indefinitely, even after you die.

Who owns your face?

Traditional intellectual property law centers on creative works: writings, art, performances. But your face and voice are more about privacy and personality rights (sometimes called “rights of publicity”). Media coverage of early digital-content disputes, like the Bruce Willis/iTunes story, highlighted how unclear things get when your “self” becomes a bundle of licenses and terms-of-service agreements.

Key problems:

- Post-mortem rights vary by jurisdiction. In some places, personality or publicity rights survive death and pass to heirs; in others, they don’t.

- Biometric data is rarely treated like inheritable property. Your heirs may have strong ethical claims but weak legal tools if they want to stop a company from using your face in training data or AI systems after you die.

- Platforms’ terms of service often give them broad rights. If you uploaded your images or videos, you may have already granted perpetual, worldwide licenses for certain uses — which might outlive you and override your family’s wishes.

Meanwhile, governments and ethics bodies were already warning about the spread of biometric systems — particularly facial recognition — and the risks they pose to civil liberties and privacy.

Put together, this means that “who inherits your face” is still largely unsettled. In practice:

- Families may be disturbed by deepfakes of the deceased but have limited recourse.

- Companies can build face-recognition or generative models using huge photo sets that include dead people, often without explicit consent.

- Your own wishes about post-mortem use of your image and voice might have no clear legal mechanism behind them yet.

So what can you actually do?

Law and policy are still catching up, but you can make your digital afterlife a bit less chaotic:

- Appoint digital executors. Decide who should manage your email, cloud storage, social profiles, and domain names — and put this in writing alongside your traditional will.

- Use built-in tools. Turn on Google’s Inactive Account Manager, consider Facebook’s legacy contact or deletion option, and check what similar tools your other platforms offer.

- Document your wishes about memorialization. Do you want your accounts deleted, frozen as memorials, or actively managed as tribute pages? Spell this out for your family.

- Plan for subscriptions and digital businesses. Make sure someone can access the accounts that keep important services and income streams running — or shut down what you don’t want to continue.

- State preferences about your image and voice. Even if the law is fuzzy, you can clearly write that you do or do not consent to your likeness being used in AI avatars, deepfakes, or post-mortem commercial projects.

You can’t control everything that happens to your data after you die — but you can make things far easier, and far less creepy, for the people you leave behind.