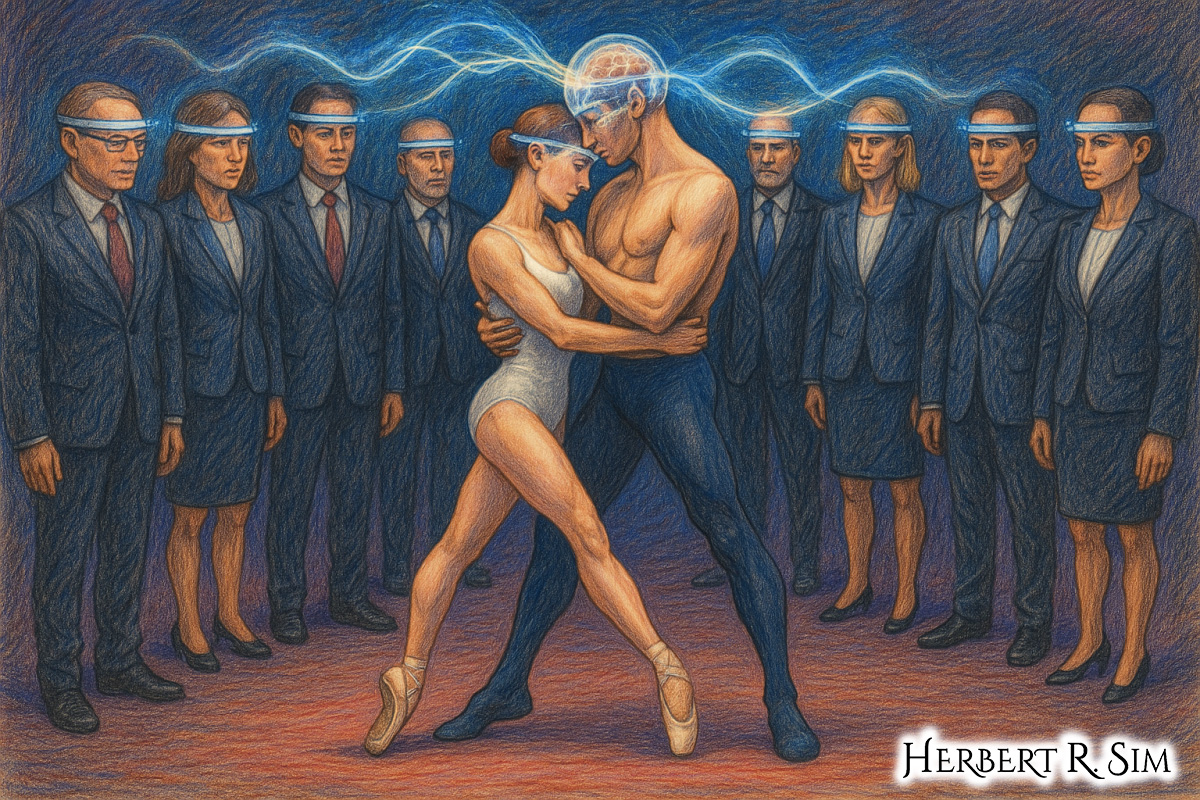

In my illustration above, I feature a group of executives enjoying the pleasure of the dancers’ interaction with each other, via the brain-computer interfaces – Neural bands, aka Neurochip.

Imagine a world in which the private, visceral experiences of human pleasure — orgasm, deep gustatory ecstasy, the surge of endorphins from indulgence — could be transferred, like a currency, from one brain to another. Picture a wealthy individual buying the “right” to feel the orgasm of a couple synced in real time via neural bands, or paying a person to binge eating and hand over the neurochemical rush — without the calories, without the weight gain, without the risk of diabetes. With emerging brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, this speculative premise is accelerating from science fiction toward plausibility.

In this article I will explore how the technology is developing, what a path toward such a pleasure-transference economy might look like, and the ethical, social and economic fault-lines it would surface — especially when the rich literally pay the poor to experience their pleasure.

From prosthetics to shared sensation

BCI research has thus far focused on therapeutic applications — allowing paralyzed individuals to control prosthetic limbs, restoring communication for locked-in patients, decoding brain signals for cursor control. As noted in the seminal Wired piece, “The Brain-Machine Interface Isn’t Sci-Fi Anymore.” Another review in Nature emphasises that as BCIs become more complex, ethical issues proliferate.

At the same time, the horizon for BCIs includes “neural co-processors” — devices that not only decode brain signals but encode artificial inputs, closing the loop from brain to external device and back.

In other words: if we can read from the brain and eventually send signals into it, the possibility arises of transmitting experience — sensory, affective, or even pleasurable — from one brain to another.

The scenario: pleasure as tradable experience

Let’s imagine a future scene. A couple chooses to wear a “neural band” (a non-invasive headset) or a neurochip implant. During sex, their brain activity is not only recorded but encoded and streamed to a remote receiver (a “pleasure node”) worn by a subscriber. That subscriber — let’s call them A — feels the physiological and affective surge: skin flush, muscle tension, rush of neurotransmitters. Meanwhile the couple themselves may receive payment from A: they transfer their pleasure to A in return for money.

Another scenario: a gourmand indulges in a sugar-rich dessert, experiencing waves of euphoria, endorphin surges, dopamine hits. Instead of merely logging the treat for themselves (and gaining weight, risking diabetes), they strap on the neural device and monetize the neuro-rush. A remote user B buys access to the recorded or live stream, and experiences the high without ingesting the calories.

In this economy, pleasure becomes a commodity. The “rich” buy the sensation; the “poor” or “disadvantaged” earn money by providing it. Pleasure is outsourced. The rich circumvent physiological limits (metabolic cost, health risk) by paying others to do the indulging. The poor “sell” their lived sensory experiences in return for income.

TV and fiction have glimpsed similar motifs. For example, the series Incorporated (2016) depicted a dystopian future where corporations exploit human lives for profit; our scenario flips it somewhat — pleasure is harvested rather than bodies expropriated. But the core dynamic of commodified human experience is analogous.

Why this future may come sooner than you think

- Decoding + encoding affective brain states. Research on affective BCIs (devices that measure emotional and affective neural signals) is underway. Steinert and colleagues review the ethical issues of affective BCIs and note how the mapping of brain states corresponding to pleasure, arousal, emotion is plausible.

- Commercial interest in healthy augmentation. As one article asks, “Should you upgrade your brain?” the idea of BCIs for healthy humans — not just for therapy — is already under discussion.

- Shared brains and brain-to-brain interfaces. Although primitive, experiments in brain-to-brain interfaces (BTBIs) demonstrate that direct sharing of neural signals between brains is possible (though limited so far).

- Neuro-economies and platforms. The broader economy is already built around commodifying attention, sensation, and experience (think social media, streaming, virtual reality). A platform that sells neural pleasure experiences is conceptually an extension of this.

- Health-risk avoidance. The notion of vicariously experiencing pleasure (e.g., food high without calories) is appealing. It circumvents the metabolic and pathological consequences of indulgence. Thus, demand may emerge.

In sum: the convergence of technology with human desire sets the stage for a future in which transferring pleasure becomes technologically feasible, socially conceivable, and economically viable.

How the pleasure-transfer marketplace might function

Here is a conceptual step-by-step of how such a marketplace might evolve:

- Device & recording layer: neural bands or implants capture the electrophysiological correlates of pleasure (sexual orgasm, gustatory ecstasy).

- Encoding & streaming layer: captured signals are processed (filtered, encoded) into a stream that can be transmitted or replayed.

- Receiver layer: a subscriber device (wearable or implant) decodes the stream and stimulates sensations in the recipient’s brain (or evokes them via peripheral stimulation).

- Marketplace layer: a digital platform where “providers” (people offering their pleasure to be streamed) and “consumers” (people paying to experience it) connect. Smart contracts settle payments.

- Risk/health mitigation layer: the consumer side avoids the metabolic cost — no calories, no weight gain, no diabetic risk. Meanwhile, the provider side is compensated financially.

- Regulation, safety, and ethics layer: as with any new tech, issues arise around consent, privacy, mental integrity, addiction, exploitation.

A rich individual might subscribe to a service: “Tonight, I’ll stream the orgasmic experience of couple X, at a premium rate.” The couple receives payment; the subscriber experiences something akin to mélange of sensations. Another user might “purchase” a 30-minute session of extreme gastronomic pleasure from a “provider” who binge-eats and transfers the rush.

Note the inherent asymmetry: the provider endures the metabolic cost (even as perhaps they mitigate it via exercise or diet control), while the consumer reaps the benefits risk-free. The economic balance tilts toward the wealthy paying for experience, the poorer selling experience.

Social, economic and ethical implications

This scenario raises profound questions:

- Inequality and exploitation. Will this become a new frontier of wealthy pleasure-purchasing from vulnerable providers? The poor may feel pressured to “sell” their neural experiences just as now they sell labour. This could establish a class-based neuro-pleasure economy.

- Consent and autonomy. Are pleasure providers fully consenting? Is there risk of coercion or economic desperation driving participation? A 2019 paper flagged the ethical issues of affective BCIs: autonomy, consent, privacy.

- Privacy and mental integrity. If we can transmit pleasure, can we also hack, modify or hijack it? Data from brains is deeply intimate — regulation is lagging. Research emphasises that existing device-regulations may be inadequate.

- Addiction and health. What happens psychologically if one can access endless pleasure without biological cost? The classic thought experiment of the “experience machine” by philosopher Robert Nozick flagged that pleasure alone may not suffice for human flourishing.

- Identity, authenticity, and class privilege. If one can purchase someone else’s experience, does that de-value the original act? Does the provider become a “pleasure commodity”? Does the consumer lose a sense of genuine self? Social stratification may intensify: those who can pay for pleasure vs. those who must sell it.

- Health and economic externalities. If the consumer side avoids biological consequences (weight gain, diabetes), are broader societal costs still shifted toward providers or society (e.g., over-eating provider health burden)?

- Regulation challenges. How do we regulate devices that transmit subjective affective states? Existing frameworks for medical implants may not anticipate a “pleasure-market”. Ethical guidance is emerging but still nascent.

In short: the technology invites a radical re-thinking of human experience, economy and ethics.

A speculative vision of possible use-cases

- Luxury “sensory subscription” services. Elite clients pay monthly for curated pleasure streams: high-end sex experiences, exotic food binges, adrenaline rushes, meditative bliss — all delivered via their brain device.

- “Pleasure outsourcing” by providers. People in lower-income brackets register on platforms to provide their neural pleasure feed. They schedule sessions, get paid per minute or per event.

- Commercialised “pleasure farms”. Companies hire providers in bulk to generate standardized pleasurable experiences (think “pleasure farms” — akin to call centres for sensations).

- Health-alternative “negative cost” experiences. Ones who can’t or won’t indulge biologically may “rent” pleasure vicariously rather than face metabolic risks.

- Criminal or black-market streams. As with any digital resource, underground markets may emerge: unregulated, unconsented streams, hacked experiences, “live illicit pleasure” trade.

- Therapeutic uses morphing into commodification. Initially BCIs are therapeutic (for paralysis, lock-in). But once the “healthy augmentation” market opens, the slope toward pleasure-commodification steepens.

Why we must talk about it now

We are not yet in the world of outsourced neural orgasms, but the pieces are moving quickly:

- The mainstream media coverage of BCIs emphasises that the leap from therapy to enhancement is anticipated.

- Ethical scholarship shows we are ill-prepared for the affective dimensions of BCIs.

- The social backdrop of increasing inequality means the commodification of human experience is a very real possibility.

The time to debate the implications is now — before a market forms uncritically and providers and consumers become entrenched in new stratifications of pleasure and payment.

Charting possible futures

Optimistic scenario. A regulated market emerges where individuals can voluntarily offer their neural experiences for payment under strict consent, privacy and safety safeguards. Neural companies develop devices that allow safe streaming of pleasurable states, and the economic redistribution helps lower-income individuals. Society negotiates fair remuneration, caps on usage, and access for all.

Neutral scenario. We see early niche services: premium “pleasure-subscriptions” for wealthy early-adopters; providers at the margin are paid modestly, some regulatory frameworks appear, but the risk-of-exploitation remains. Pleasure remains a luxury exchange, not a right.

Dystopian scenario. The market for pleasure-transference spirals. The wealthy outsource vast amounts of pleasure; providers become “pleasure workers” in an emergent underclass whose job is to deliver live neuro-stimulus for payment, often under poor working conditions. Regulatory oversight weak. Privacy violations and neuro-hacking proliferate. Consumption becomes decoupled from resource (biological) cost for the rich, while the poor bear the physical/health burden. Pleasure becomes a class divide.

Why this isn’t mere fantasy

We’ve framed the movie-scene, but the building blocks are real:

- BCIs are no longer purely speculative. The review “Inside the Race to Hack the Human Brain” outlines ongoing commercial efforts.

- The ethics of affective BCIs have been academically explored (“Wired for Healing,” etc) and note affective states as part of BCI future.

- Scholars emphasise that as the technology becomes capable both of decoding and encoding, the “experience machine” scenario becomes less philosophical and more engineering.

Finally, referencing fiction (Incorporated, as noted earlier) reminds us that this kind of commodification of human experience is not new to sci-fi. What is new is the accelerating convergence of technology, commerce and human physiology.

Key questions for the future

- Who owns the data and the experience? If I stream my orgasm, do I still “own” it? Who controls its reuse, resale, re-packaging?

- What is the price of pleasure? If pleasure becomes commodified and market-priced, how are rates determined? Will providers compete downward (race to the cheapest thrill) or upward (premium bespoke experiences)?

- Can there be equitable access? Will the poor have access to these experiences, or will they only serve the wealthy? Conversely: will the poor become primarily providers of their own neuro-pleasure?

- What health burdens shift where? Providers may take physical tolls (overeating, stress) while consumers avoid them. How will health systems respond?

- How do we preserve authenticity and human dignity? If lived experience is outsourced, does the concept of self-pleasure or inter-subjective intimacy diminish?

- What regulatory frameworks are required? Will “pleasure marketplaces” be regulated like sex work, medical devices, or consumer electronics?

- What about mental autonomy and hacking? Once pleasure signals are transferable, are they hackable? Could undesirable entities broadcast or intercept them?

Conclusion

The idea that we might one day transfer pleasure, selling or purchasing someone else’s orgasm, binge or bliss — is provocative, perhaps discomfiting. But the science is approaching the point where what once was fantasy may become feasible: neural bands, neurochips, digital streaming of subjective states.

If the wealthy begin paying for neural experiences, paying the less-well-off to supply them, we may enter a new pleasure economy — one in which human sensations become tradable assets. That economy brings opportunity (income for providers, risk-free indulgence for consumers) but also danger (inequality, exploitation, loss of autonomy, commodification of the self).

The question is not if this future will happen — but how we will shape it. Will we build fair systems that guard dignity, consent and equality? Or will we allow a new class divide between those who pay for pleasure and those who sell it? Are we ready?

In sum: the path is being paved. The building blocks of BCIs, affective neuro-streams and human-machine sensation are already emerging. It is up to us — engineers, ethicists, policymakers, citizens — to decide if the pleasure economy becomes a tool for human flourishing, or a new vector of exploitation.