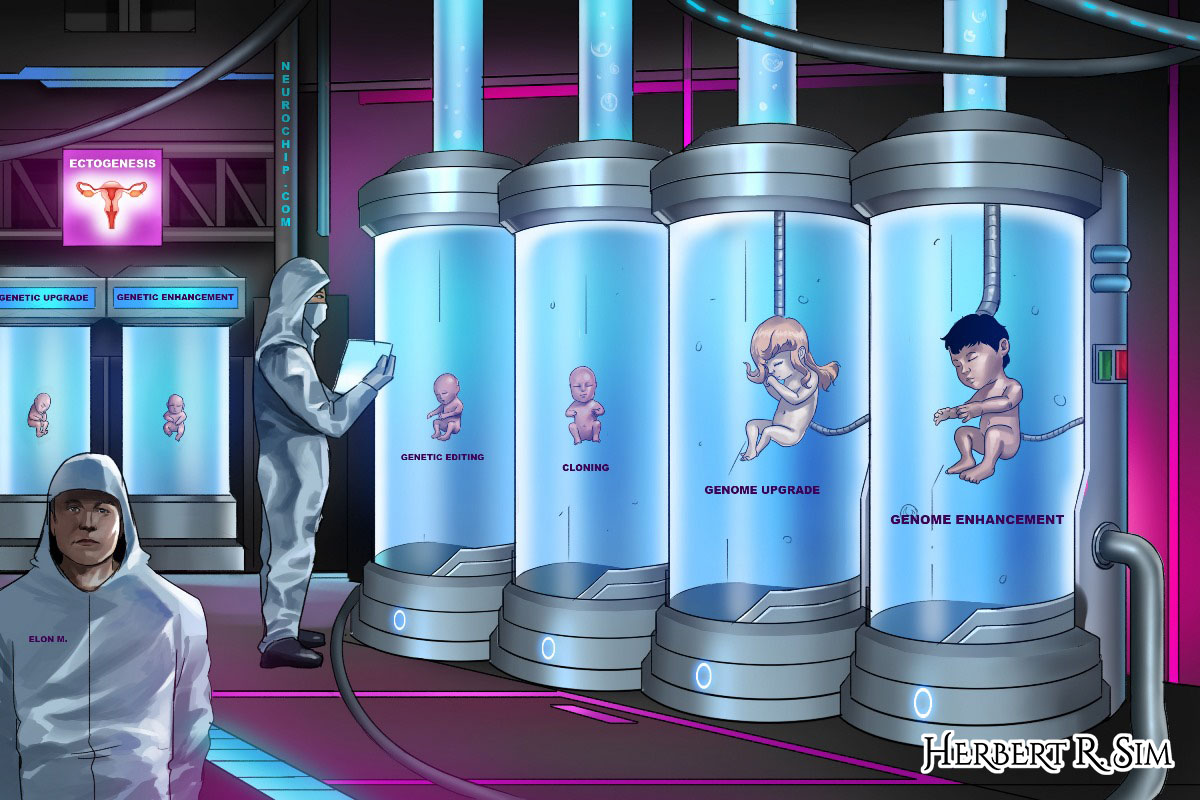

My illustration of a genetics laboratory with artificial womb chambers incubating the babies.

————————————————————

Ectogenesis, or the gestation of an unborn infant outside of the body within an artificial womb, is a concept that’s both groundbreaking and controversial.

The technology has lit a bonfire of fierce ethical-legal debate across the world, creating social constructs and permutations that could shake up the medical industry and the very essence of a biological function.

Coupled with the fact that gene-editing and cloning technologies have both developed at such breakneck speed, the idea of creating artificial wombs would seem to fan even more momentum – specifically towards the usage of these technologies and how they can complement one another.

The technology to create artificial wombs and enable ectogenesis is closer than ever before, and when such initiatives become prevalent, gender parity and the potential emancipation of women could well and truly begin.

Artificial wombs with an authentic mission

There’s a noble cause behind the idea of creating artificial wombs, which is to save the most vulnerable human beings on earth – specifically, extremely premature babies.

This narrative was seeded by the creators of BioBag, a type of artificial womb that acts like an amniotic sac filled with lab-made fluid – complete with a replacement placenta and tuned to replicate actual womb-like conditions.

The BioBag prototype was conceived after three years of experimenting, gaining prominence after the researchers found a way to gestate sheep fetuses outside of maternal bodies. The fetuses eventually became lambs no different from those that are grown in ewe wombs.

The trials provided a glimpse into what could eventually transpire on the horizon, especially in terms of genetic engineering and medical expertise. Of course, other experiments have served to reinforce the conviction that artificial wombs are entirely possible.

For example, researchers from the Eindhoven University of Technology and Weizmann Institute of Science are making inroads with their respective trials. In fact, the latter has managed to grow mice embryos within glass jars for as long as 11 to 12 days, a breakthrough considering it is half the animal’s natural gestation period.

If lambs and mice could gestate smoothly in test tubes and glass jars, and if, in theory, premature babies could reasonably be subjected to partial ectogenetic procedures, human cloning could really take a giant leap forward once full ectogenesis is proven effective.

Manchester University has even predicted that human testing for partial ectogenesis could actually begin in five to 10 years’ time – signifying how far the technology has come. As for full ectogenesis, research efforts are underway to render it possible for the ova to be grown into embryos and sustained in vitro.

————————————————————

If you notice on the left, the laboratory guy, I sketched in to resemble Elon Musk.

————————————————————

An opportunity for cloning and gene-editing experts

Essentially, an artificial womb is designed to help gestate a fetus to term outside a human body, complete with a fetal heart and umbilical cord to enable circulation. It will also deliver an environment that is free from diseases and pollutants – which are aspects that can sometimes be found inside a human womb.

In theory, an optimal womb condition is capable of lowering the risk of premature birth, helping the fetus to gestate to term and increasing its survival rate. Premature babies will also no longer have to deal with the high risk of disability or chronic illnesses that are associated with extreme prematurity.

Such an ability to tweak and incorporate the right conditions would be ideal for human cloning experiments – which despite being controversial, could also pave the way for gene-editing experts to enter the picture.

Case in point, the ideal scenario for these researchers would be to first execute a cloning process by moving a choice DNA into a preferred egg cell, before implanting it into an artificial womb for gestation. Gene-editing processes can then be introduced in the early stages of human embryo development, apart from altering the womb conditions, which could lead to the development of an “ideal” baby.

Social disruption and female emancipation

On the social-ethical front, gender parity is perhaps one of the more prominent side effects of normalising the successful use of artificial wombs. In fact, many experts have pointed out that ectogenesis could herald the era where true equality would exist between all sexual denominations.

Furthermore, scaling up ectogenetic processes is extremely complex, involving more than just legal and ethical challenges, but also social and cultural constructs that could determine the potential uptake of such a technology.

Abortion is one such minefield that could be redefined by the presence of artificial wombs. Simply put, if a mother decides not to keep her baby, the availability of artificial womb technology to gestate the baby to full term and then give it up for adoption could affect abortion practices.

Abortion would thus become a simultaneous declaration of pro-life and pro-choice: Why should the mother be given the choice to abort her baby if artificial wombs can save the baby’s life?

Also, if creating an artificial womb is already confined within ethical and legal boundaries, then the possible introduction of genome editing and cloning efforts would present even more barriers.

Cost-wise, ectogenetic procedures would be expensive and available only in hospitals that are equipped with advanced neonatal intensive care units. This will lead to an even wider disparity between the rich and poor countries, promoting inequality in terms of health outcomes for mothers and babies.

————————————————————

In my final masterpiece, in full color, you see the detailing in of the rest of the genomics laboratory. I added in the text into the art as well, in case it wasn’t clear enough.

————————————————————

Blockchain’s rise may prove instrumental

By tackling the hurdles that artificial wombs may encounter, it would lead to a quicker acceptance – just like how IVF (in vitro fertilisation) used to be – a revolutionary technology that became widespread and commonplace.

When this occurs, the potential emancipation of women could be far-ranging and more effective than ever imagined, and women will no longer be valued for just their reproductive capabilities.

Better yet, with blockchain technology burgeoning in popularity, it could even find its place within the complicated web of gene-editing, cloning and ectogenetic research. Blockchain can be instrumental in storing genome data and when such statistics are properly analysed and tapped by researchers to understand what’s needed to conceive a “high performing” human being (think Captain America or the idea of creating a super soldier), then perhaps the visualisation of a dystopian world with test tube babies and lab coats aren’t just a sci-fi nightmare but a reflection of a plausible future.

However, with ever-present ethical and legal barriers, at what cost would it take to break them? Or can blockchain’s anonymity and reliability be part of a concerted effort to tackle gender inequality, preserve mankind and enable people to control their own genome data – and possibly, dictate their legacy?

The answer lies in the progress of respective technologies and right now, those with glass jars and test tubes are setting the pace.