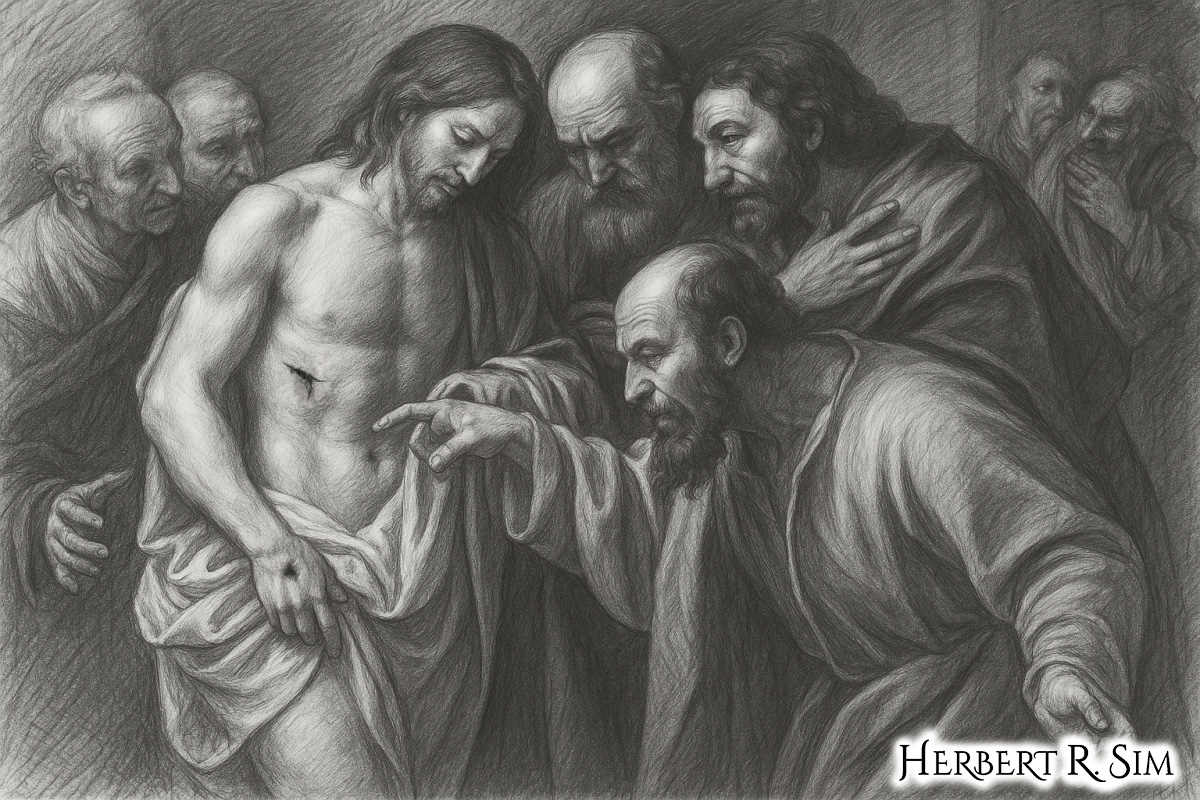

Above is my illustration featuring the ‘Gospel of Thomas’, inspired by The Incredulity of Saint Thomas is an oil on canvas painting by Caravaggio.

When a jar of papyrus codices was dug up by farmers near Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt in 1945, few could have guessed how much they would unsettle our picture of Christian origins. Among those codices lay a slim but explosive work now called the Gospel of Thomas – 114 sayings attributed to Jesus, with no birth narrative, no miracles, no crucifixion and no resurrection story.

For decades now, journalists, reviewers, and public intellectuals have followed scholars in asking what this “lost gospel” might mean for history and for faith. Time magazine’s early coverage hailed Thomas as a remarkable glimpse into an alternative strand of early Christianity, even while stressing its “Gnostic” tone and its distance from church orthodoxy. The result is that the Gospel of Thomas has become not just a scholarly curiosity, but a recurring character in modern conversations about Jesus.

What is the Gospel of Thomas?

Thomas is a sayings gospel: short, often enigmatic aphorisms placed on Jesus’ lips, many with parallels in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and others without any known canonical equivalent. One Los Angeles Times story, summarizing research on Nag Hammadi writings, notes that Thomas is an early Christian text preserved in Coptic, part of a cache of 52 works buried after bishops ordered “heretical” books destroyed.

Instead of telling readers what happened to Jesus, Thomas asks them to wrestle with riddling statements about the kingdom, the self, and divine light. A typical saying runs along the lines of: the kingdom is not in the sky or in the sea, but “inside of you and outside of you” – a theme several mainstream articles quote in discussions of Thomas and Gnosticism. The tone is meditative, almost zen-like, and that has encouraged many modern readers to use Thomas as a resource for contemplative spirituality rather than for dogma.

Discovery, dating, and debates

The codex containing Thomas came to light in the mid-20th century, but journalists writing for the general public often stress that the text itself is much older – probably a second-century composition, though some argue for earlier layers. Stories in major newspapers and magazines highlight how its discovery forced scholars to revisit an older narrative in which orthodoxy simply marched forward and “heresy” trailed behind. Elaine Pagels, frequently profiled in these pieces, has been especially influential in framing Thomas as evidence of a once-vigorous diversity inside early Christianity.

Reporters covering the Jesus Seminar in the 1990s picked up on another controversy: does Thomas preserve some sayings of Jesus in an earlier, perhaps more primitive form than the canonical gospels, or is it a later patchwork dependent on them? A widely read Newsweek feature on the Seminar noted that its fellows took Thomas seriously enough to treat it as a “fifth gospel,” even color-coding Jesus’ sayings in Thomas alongside those in Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Not all scholars agree, but that prominence in public reporting has helped normalize the idea that Thomas belongs at the table whenever historians rebuild the earliest memories of Jesus.

Thomas and John: dueling visions of Jesus

If one modern work has done more than any other to bring Thomas into mainstream media, it is Elaine Pagels’ 2003 bestseller Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. In reviews and interviews, journalists repeatedly return to her central claim: that the canonical Gospel of John reads, in part, as a deliberate rebuttal to the theology of Thomas.

Guardian and Stanford reviewers emphasized this contrast for general readers. In their summaries, Thomas portrays Jesus as a teacher revealing the divine light already present in each person, while John presents Jesus as the unique “light of the world” through whom alone believers come to the Father. Where Thomas urges individuals to “know themselves” and discover that they are children of the living Father, John underlines faith in Christ as the decisive path to God. That tension – inner illumination versus Christological exclusivity – has become a staple of newspaper and magazine discussions about why some early Christian writings made it into the New Testament while others did not.

Christian Science Monitor pieces on Pagels and related scholarship frame Thomas as one exhibit in a broader “ongoing evolution of Christianity”, suggesting that the canon we know captured only part of a much wider conversation.

Gnosticism, heresy, and the “secret” teachings of Jesus

Media coverage often places Thomas under the banner of “Gnosticism”, though reporters also reflect scholarly caution about the label. From the 1970s onward, Time, the Washington Post, and others portrayed the Nag Hammadi codices as the library of a largely lost “gnostic” movement that prized direct knowledge (gnosis) of God and often cast the material world as a prison.

Articles explaining Gnosticism to general audiences regularly single out Thomas for its emphasis on interior transformation. In the words of one Washington Post essay, citing Thomas directly, the text urges readers to “bring forth what is within you,” warning that what remains unrealized may in fact destroy you. That line has become something of a media shorthand for the gospel’s psychological, almost therapeutic tone.

At the same time, mainstream outlets are quick to note that Thomas is not simply a self-help manual in ancient clothing. Stories about museum exhibits, manuscript discoveries, and public lectures stress its roots in early Christian communities for whom visionary experiences and ascetic practice were serious, sometimes dangerous commitments.

From papyrus to prime time: Thomas in contemporary culture

By the 1980s and 1990s, Thomas had moved from specialist journals into the broader cultural imagination. Features in the Los Angeles Times and Washington Post tied interest in the text to wider debates about Mary Magdalene, the historical Jesus, and the authority of church institutions. The Da Vinci Code boom of the early 2000s only amplified this visibility, with columnists and reviewers pointing readers toward Nag Hammadi texts – including Thomas – as the real scholarly backstory behind the fiction.

Stanford Magazine’s 2004 profile of Pagels, tellingly titled “The Gospel Truth,” presented Thomas as both a key to the past and a mirror of present-day spiritual searching. The piece echoes something many popular articles note: for some modern readers disenchanted with institutional religion, Thomas’ Jesus sounds less like a cosmic ruler and more like a guide to inner awakening.

Newspaper book sections, meanwhile, treated Beyond Belief as part theology, part intellectual memoir. Reviews in major dailies and regional papers describe how Pagels weaves her own experience of grief and churchgoing into a meditation on Thomas’ message, and several “top books of 2003” lists highlighted her work precisely because it made a notoriously obscure gospel accessible to lay audiences.

Thomas vs. the creeds

For all the fascination it inspires, the Gospel of Thomas sits uneasily alongside the doctrinal formulas that defined mainstream Christianity. Newsweek’s coverage of contemporary debates about Jesus repeatedly underscores this point: if one takes seriously the sort of historical reconstructions favored by Jesus seminar – style scholars – who lean on texts like Thomas – then “every important article of the traditional Christian faith goes out the window.”

That stark phrasing reflects a tension that many journalists pick up on. On one hand, Thomas appears to offer a stripped-down Jesus whose authority lies in wisdom teaching rather than in miracles or a saving death and resurrection. On the other hand, as Christian Science Monitor and PBS programs point out, the canonical gospels and the creeds were precisely what allowed Christianity to cohere as a public, sacramental movement rather than dissolving into a multitude of esoteric circles.

This double perspective – Thomas as both a precious witness to lost possibilities and a challenge to received belief – gives the text much of its dramatic power in media narratives.

Spirituality, equality, and the attraction of a “secret” Jesus

One recurring theme in coverage from outlets like the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times is the way Thomas (and related texts) imagine spiritual authority. Instead of a rigid hierarchy, many Nag Hammadi writings suggest circles in which women and men share leadership and in which inner experience, not office, confers status. That has made Thomas attractive to readers interested in feminist theology, alternative Christianities, and more egalitarian religious practice.

At the same time, some commentators are wary. First Things and other opinion magazines caution that the individualistic “spark of divinity within” language associated with Thomas can feed a highly personalized spirituality detached from communal accountability. From this point of view, the gospel’s appeal in contemporary culture says as much about us – our focus on authenticity, choice, and inner life – as it does about first- and second-century Christians.

So what does the Gospel of Thomas mean today?

Stepping back from the headlines, a few consistent threads emerge from mainstream reporting on the Gospel of Thomas over the last several decades. First, Thomas has helped the wider public grasp that early Christianity was not monolithic. There were multiple ways of telling the story of Jesus and multiple ways of practicing what it meant to follow him. Journalists from Time to the Christian Science Monitor underline that the New Testament canon represents one successful stream within a more complex river.

Second, Thomas forces a fresh look at familiar questions: Is salvation primarily about believing certain things about Jesus, or about undergoing a transformation that reveals the image of God already within us? Are religious institutions guardians of a life-giving tradition, or gatekeepers who sometimes suppress other voices – like those preserved in Nag Hammadi jars? Media profiles of Pagels and museum reports about ancient manuscripts show how compelling those questions remain for modern readers.

Finally, the Gospel of Thomas illustrates the complicated relationship between history and faith. Historically, it is one witness among many to the ferment of the first Christian centuries. Theologically, different communities will continue to disagree over whether its vision can be reconciled with creedal Christianity. What is striking is that, thanks to the patient work of scholars and the storytelling of major newspapers, magazines, and broadcasters, this once-buried text now plays a living role in public conversations about who Jesus was – and what his message might still mean.