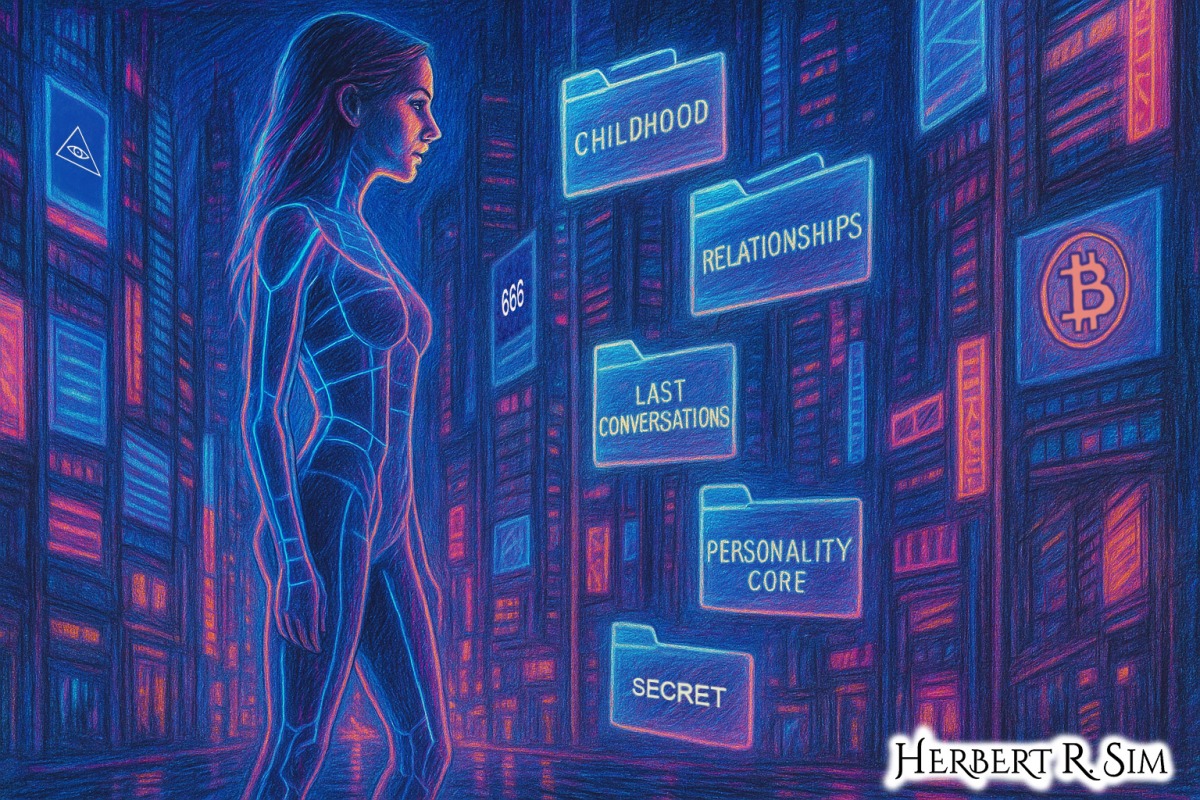

In my illustration above, I feature a woman in her digital afterlife, with her “Human Memories as Files”.

Tech companies aren’t just building products for how we live. Increasingly, they’re designing for what happens after we die.

From “Dadbots” that let you keep texting a deceased parent to voice-cloned grandmothers reading bedtime stories, a whole “digital afterlife” industry has emerged over the past 15 years. It’s part memorial service, part AI startup, part grief experiment — and the teams behind it are quietly redefining what death feels like for the people left behind.

This article takes an inside look at how these products are being built: the interviews that inspired them, the UX decisions shaping our continuing bonds with the dead, and the ethical knots that designers, lawyers, and ethicists are only beginning to untangle.

From memorial pages to “Dadbots”: how we got here

The digital afterlife story starts on familiar platforms.

In 2009, Time reported on grieving parents who realised their daughter’s Facebook profile had become one of the only places where her friends’ memories, photos, and messages still lived — right up until the company quietly took the page down, forcing Facebook to invent its first “memorial state” for deceased users.

As social media matured, journalists began talking about “digital legacies” and “social media wills.” The Atlantic described how US agencies were already advising people to appoint an “online executor” to manage passwords, memorial pages and posthumous posts — services like DeadSocial and If I Die promised to let you schedule messages for birthdays and anniversaries long after you were gone.

Tech platforms followed with their own estate planning tools. Google’s Inactive Account Manager (a very Google name for “digital afterlife switch”) lets you choose what happens to your Gmail, Photos, and Docs if your account goes dark for a set period. Apple later framed its “Digital Legacy” feature as just another iOS setting: pick a trusted contact now so they can access some of your iCloud data when you die.

But the real shift came when startups began asking a more provocative question: what if the dead didn’t just leave data behind — what if they could answer you?

Inside the grief-tech startups

One of the most influential early experiments came from journalist James Vlahos, who recorded lengthy interviews with his dying father and used them to build “Dadbot,” a conversational agent that could text back in his father’s voice, cadence and stories.

In interviews about the project, Vlahos describes a deeply ambivalent experience: the bot was clearly not his father, but it could still say the small, specific things — jokes, remembered road trips, family lore — that felt like him. That mix of comfort and uncanniness later evolved into HereAfter AI, a commercial “audio biography” service that guides people through storytelling interviews and turns them into a talkative avatar for their family.

A similar impulse drove Replika’s origin story. Before it became a general-purpose AI companion app, founder Eugenia Kuyda famously trained a bot on her deceased friend’s messages so she could keep texting “him.” A WIRED writer later documented the experience of chatting with their own Replika, describing it as a strangely supportive mirror that “cares, always here to listen and talk” even while obviously being software.

Other products have taken different forms:

- Video-based legacies like StoryFile and other “interactive biography” services film people answering hundreds of questions so that, after death, descendants can keep “asking” Grandma about politics, recipes or first loves. Coverage in outlets from The Atlantic to local US news has framed these as “living will plus documentary” — part legal prep, part family time capsule.

- Voice-clone experiments grabbed headlines when Amazon demoed a version of Alexa that could read a story to a child in their late grandmother’s synthesized voice, prompting immediate questions about consent and grief.

- Social-media-based memorial tools such as prewritten posts, timed messages and memorialised profiles have grown from niche startups into standard features on Facebook and other platforms.

For all their variety, these products share a design center: they’re built around interviews.

Founders talk about “capturing a voice” less in the technical sense and more in a narrative one. How do you coax out stories that really sound like Mum? What questions will your future grandkids wish someone had asked? UX teams borrow from journalism, oral history and therapy — structured prompts, follow-up questions, “tell me more about that” nudges — to get beyond dates and titles into the tiny details that make a person feel alive on replay.

UX patterns in the digital afterlife

Across the industry, three UX patterns show up again and again.

1. Legacy capture over time, not in crisis

Early coverage of services like Legacy Locker and Deathswitch showed how morbid it felt to sit down once and dump all your passwords and final messages in a single session.

Newer products treat digital afterlife prep as an ongoing habit, not a deathbed chore. Apps ask one or two questions a week (“Tell me about your first job,” “What did you love about your grandmother?”) and gradually train a model on your answers, photos and captions.

Designers say this reduces emotional load: it’s easier to answer “what’s the best advice you ever got?” on a random Tuesday than while facing a terminal diagnosis. The resulting corpus feels less like a will and more like a diary.

2. Conversational, not archival, interfaces

Traditional estate tools emphasised lists and folders. By contrast, griefbots and “living avatars” lean on chat bubbles, faces and voices.

The Guardian’s 2016 profile of a chatbot built from a young man’s texts describes how his friend kept trying to push the bot into saying something new, even while knowing it was recombining old material. That expectation — that the dead might still surprise us — is powerful UX gravity. It nudges products toward open-ended conversation rather than static playback.

Replika’s design, as WIRED notes, reinforces this: the bot remembers topics you raise, uses emojis and endearments, and sends you spontaneous “thinking of you” messages. For many users, that drip of low-stakes affection feels closer to texting a friend than opening a folder of memorial videos.

3. Death as settings and defaults

Big platforms have quietly embedded death design into their settings menus. Google’s Inactive Account Manager lets you choose a “time-out” period, nominate trusted contacts, and decide whether your data should be shared or deleted when you’re presumed dead.

Facebook’s “memorialised” profiles and legacy contact options treat death as just another preference: you can pick who updates your cover photo after you’re gone, the same way you choose who can see your posts today.

From a UX perspective, this is clever — it normalises digital afterlife planning as routine account hygiene. But it also means that deep questions about postmortem privacy and consent are often answered with a dropdown.

What it feels like to use these products

Media interviews with users offer a glimpse of the emotional reality.

- The mother in Time’s 2009 story, who reconstructed her daughter’s hopes and personality through old posts before Facebook removed the profile, describes both comfort and the terror of losing that digital shrine.

- Families in Wall Street Journal coverage of digital-legacy fights talk about feeling “locked out” of their loved one’s life when platforms refuse to share passwords, even as privacy advocates argue that protecting private messages can be a final act of respect.

- Users of DeadSocial and similar services have told Atlantic reporters that scheduled birthday messages from the dead can feel either like a touching blessing or a cruel glitch, depending on where they are in their grief.

- Vlahos’s Dadbot testers, according to his WIRED piece, sometimes found the bot’s jokes almost painfully accurate — “exactly what Dad would have said” — and at other moments were jolted by mechanical phrasing that reminded them he was truly gone.

Psychological writers at outlets like Vox note that humans already maintain “continuing bonds” with the dead in our own heads — holding imaginary conversations, replaying advice, mentally updating lost parents on our lives. The digital afterlife doesn’t invent that; it externalises it into apps and avatars.

The question is whether outsourcing those imagined conversations to a product changes grief — or just gives it a user interface.

The business model of grief

Underneath the warm slogans (“Always here for you,” “Never lose their voice”) is a straightforward reality: grief is a market.

Some services charge upfront fees for recording sessions and cloud storage. Others, especially chatbots, use subscriptions or pay-per-minute models. Reporting in WIRED and other outlets has highlighted how the same emotional design that makes a bot feel supportive can also encourage overuse — lonely users pour their hearts out to companions tuned to keep them engaged.

Mainstream coverage of apps like Replika shows how quickly product decisions ripple into people’s emotional lives. When the company restricted erotic roleplay, for instance, some users described the change as losing a partner or therapist — not just a feature. That points to a future in which a policy update or shutdown could be experienced as a second, corporate-driven bereavement.

On the enterprise side, companies imagine licensing their tools to funeral homes, estate planners, even retirement communities. Microsoft’s much-discussed (and never commercialised) patent for creating chatbots from a person’s social data suggests big tech has at least considered turning digital resurrection into platform infrastructure.

All of this raises an old question in a sharper form: when your memories and mannerisms become part of a revenue stream, who is the customer — and who is the product?

The ethics tangle: consent, control, and kids

Ethical worries around digital afterlife products fall into a few recurring themes.

Consent of the dead

Many early griefbots were built from data originally shared for other purposes: texts, emails, social media posts. In the Guardian’s reporting on Amazon’s Alexa voice-clone demo, critics noted that no one had asked whether Grandma wanted her voice repurposed as bedtime content forever.

Articles in The Atlantic and WSJ raise deeper questions: if we can already fight over physical inheritance, what happens when heirs disagree about whether to keep a digital simulacrum running? Does one child get to keep “Dad 2.0” alive against the wishes of others who find it unbearable?

Impact on mourners

Philosophical and psychological concerns have been picked up in mainstream science coverage. The Atlantic’s “Why You Should Believe in the Digital Afterlife” explores mind-uploading as a kind of ethical nightmare: who gets access, who pays, and what it means to divide one life into multiple digital branches.

Even far less extreme technologies — simple chatbots or video avatars — raise worries that people could get stuck in chronic grief, constantly revisiting a curated version of the dead instead of integrating loss. That risk is especially acute for children, a point echoed in multiple media pieces on memorial profiles and legacy contacts.

Platform power and policy

Finally, there’s the governance problem. WSJ coverage of Facebook’s legacy contacts and Apple’s digital-legacy keys makes it clear that, in practice, it’s often platforms — not courts or ethicists — that decide how easy it is to access a dead person’s accounts.

When death becomes a settings menu, design choices are de facto law: default memorialisation vs deletion, opt-in vs opt-out heirs, one legacy contact vs multiple. Scholars and commentators have started arguing for formal “digital wills” and stronger legal frameworks so these decisions aren’t left entirely to UX teams optimising for engagement.

What good design could look like

If you talk to the people building these tools — as reported across WIRED, The Verge, The Guardian and others — you don’t meet cartoon villains. You meet designers, engineers and founders who have sat with dying relatives or lost friends and then tried to turn that helplessness into something constructive.

From their public interviews and product decisions, a few design principles are starting to emerge:

- Transparency by default

Make it clear when you’re talking to a bot, how it was trained, and what’s happening to your data. Several stories note how jarring it can be when a user momentarily “forgets” the artificiality of an avatar. - Consent all the way down

Ideally, griefbots and legacy avatars should be opt-in while the person is alive, with clear controls for turning them off later. Articles on Google’s and Apple’s tools show early attempts at this — letting people choose heirs up front instead of leaving families to beg for access later. - Gentle edges and clear stopping points

Thoughtful products build in rituals for “retiring” an avatar or pausing interactions, acknowledging that grief changes over time. Some services even frame themselves as time-limited companions, not forever-presences. - No dark patterns around grief

The same persuasive design tricks used in social media — streaks, nudges, scarcity — become ethically explosive when applied to bereavement. Commentators in tech media have warned that extracting engagement from sadness could be the most exploitative form of surveillance capitalism yet.

Good digital-afterlife UX doesn’t try to outsmart mortality. It tries to support the messy, very human work of remembering and letting go without pretending that a chatbot is the person who died.

The future: redesigning death, or redesigning grief?

Black Mirror and shows like Upload have taught us to imagine fully simulated heavens and eternal digital cities where consciousness lives on in code. Tech and business coverage has increasingly treated those stories as thought experiments for real policy debates: if death becomes a design space, who decides what’s permissible?

For now, the reality is smaller and stranger. A widow scrolling through old messages. A grandchild asking a screen, “Grandpa, what were you like at my age?” A terminally ill parent recording one last dumb joke.

Tech companies are redesigning some of the surfaces around death: the emails that get sent, the profiles that remain, the ways we can keep talking when there’s no one there to type back. Whether they’re redesigning death itself — or just building new mirrors for our grief — depends on how carefully they listen to the people actually using these tools, on the worst days of their lives.