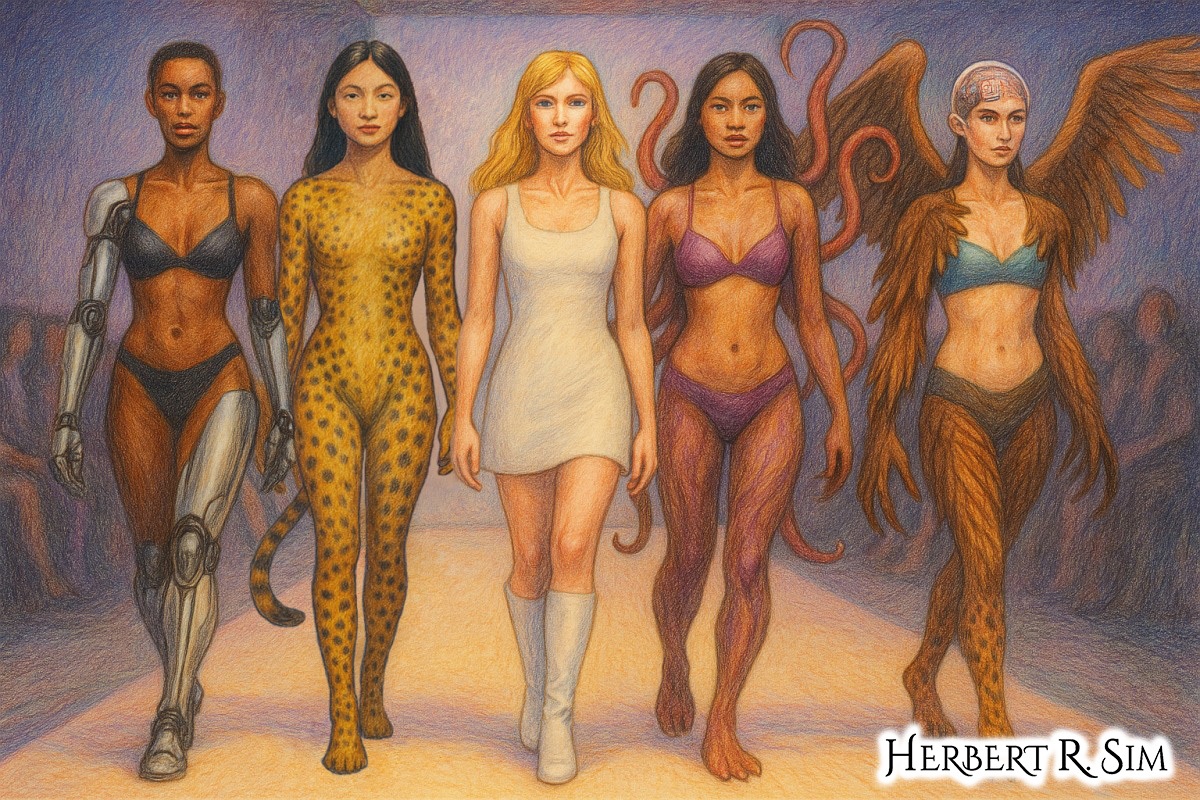

Above is my illustration of Cultural Aesthetics and Transhumanism Beauty. The standard of beauty is redefined, bionic and genetic modifications are beautiful as well.

(L-R) An African woman with robotic limb upgrades, an Asian woman spliced with cheetah genetics, an unmodified human woman, an Indian woman enhanced with octopus limbs, a Latina woman enhanced with Eagle and cheetah genetics, with a neurochip embedded in her transparent skull.

In discussions of morphological freedom, transhumanism is often framed in terms of ethics, enhancement, and social inequality. Yet the aesthetic dimension—the way bodies are seen, styled, judged, and transformed—deserves central attention. In fact, cultural aesthetics may be the arena where power over bodies is most insidious: not by outright prohibition, but via normativity, surveillance, and the valorization of particular forms.

This essay revisits and expands your earlier outline, integrating press discourse and journalistic snapshots to illustrate how aesthetics already mediates bodies in sociotechnical contexts, and how enhancement regimes might radicalize or distort these dynamics.

I proceed in three moves: (1) how media and culture shape aesthetic norms today, (2) how morphological freedom might amplify or contest those norms, and (3) possible futures and cautionary trajectories.

Part I: Aesthetic Norms in Media and Everyday Life

Media, Beauty, and the Visual Regime

Mainstream media play an outsized role in shaping which bodies are visible, desirable, and legible. In a Time experiment, a single photograph sent to Photoshop artists in twenty-five countries was retouched differently depending on local norms — changing skin tone, eye shape, makeup, and hair — thereby exposing how deeply aesthetic ideals vary across cultures. “This Is What the Same Woman Looks Like Photoshopped in Different Countries.”

Likewise, Wired has documented how algorithmic cosmetic planning is remaking facial ideals. In “Digital Culture Is Literally Reshaping Women’s Faces,” Elise Hu reports on how beauty clinics use machine learning models to derive a “global ideal” facial map and recommend features for surgeries or enhancements. This is a telling intersection of aesthetics and technics: machines become aesthetic agents, telling bodies how they should look.

In another Wired piece, “The Hypocrisy of Judging Those Who Become More Beautiful,” Sheon Han questions why we celebrate corrective interventions in infrastructure or medicine—but often stigmatize cosmetic enhancement. The article probes the tension between justice and “lookism” (discrimination based on appearance).

These media frames already situate bodies as projects: sites of modification, optimization, and surveillance. The aesthetic gaze is no longer just human — it is algorithmic, infrastructural, and normalized.

Surveillance, Discipline, and the Internal Gaze

As Michel Foucault argues, modern societies govern bodies by making them visible and legible to power. Individuals internalize monitoring, censoring what is seen, how one dresses, how one moves. Thus aesthetics is already policed.

Press reporting on beauty standards often reinforces this internal gaze. Consider the coverage of global beauty norms: skin whitening, hair straightening, double eyelid surgery, etc. These shifts are not just cosmetic — they encode racial hierarchies and histories of colonialism. Scholars and journalists refer to the phenomena of “whitewashing” in global media, where nonwhite bodies are lightened digitally or stylistically to approach Eurocentric norms.

At the same time, the body positivity movement attempts to challenge those norms. While not always covered in the context of morphological freedom, press outlets have highlighted body positivity and its contradictions: e.g. when body-positive influencers gain followers, then lose weight or change their appearance, provoking public debate. Some articles read this as betrayal, others as the impossibility of resisting visual culture.

In sum: media and cultural discourse supply both the terrain of critique and the fuel for aesthetic self-compliance.

Part II: Morphological Freedom and the Aesthetic Pressure

From Cosmetic Enhancement to Morphological Projects

In many ways, morphological freedom scales up what is already in motion: cosmetic surgery, body modification, style, tattoo, piercing, hair design. Anders Sandberg’s account of morphological freedom situates these practices as precursors to radical body design.

But the difference is magnitude. Rather than discrete cosmetic interventions, morphological freedom entails potentially systemic redesign: limbs, skins, hybrid parts, dynamic textures. In that shift lies the aesthetic risk: the environment in which re-design becomes ordinary may pivot toward normativity, not divergence.

The idea of “transhuman aesthetics” has been explored in both speculative theory and media contexts. A nonacademic blog on Transhumanity, “The Aesthetics of Transhumanism,” positions body modification as “biological art,” suggesting bodies as design artifacts. While not peer reviewed, it signals how creative discourse is already narrating bodies as aesthetic events.

Melanie Grundmann, in “Transhumanist Arts: Aesthetics of the Future?”, draws parallels between futurist dandyism and modern morphological self-fashioning. The idea is that the body becomes a technological spectacle, a visible locus of identity and progress.

In academic spheres, the genre of transhumanist or posthuman art seeks to imagine new morphological futures — glitch, hybrid, synthetic forms — as aesthetic experiments. Transhuman Aesthetics: The New, the Lived, and the Cute is one such collection. But these often remain marginal rather than normative.

The Reinscription of “Desirable Traits”

One of your core concerns is that morphological freedom could reinforce dominant traits as aesthetic ideals. This is a legitimate worry.

As enhancements scale, the “cost” of divergence may rise. If technological variation is expensive, only privileged individuals can explore radical forms; others may gravitate toward cosmetic convergence — the aesthetic of “best” in an optimization economy. The aesthetic field may narrow, not expand.

Moreover, machine models reading large datasets of faces and bodies already infer which forms are “desirable.” When these models guide enhancements, they may codify bias: symmetry, particular proportions, skin smoothness, feature alignment. In short: algorithmic aesthetics may inherit the biases of historical data (race, class, gender) and reproduce them in embodied form.

The Wired article on algorithmic beauty (cited above) is one indicator how this process is already underway. The algorithms do not merely reflect norms — they actively shape demand and possibility.

In effect, morphological freedom may not liberate aesthetic diversity; it may formalize normative pressure via technology.

The Illusion of Autonomy

A common rhetoric of enhancement is that we choose our body — yet “choice” is never unconstrained. Social, normative, and aesthetic pressures mediate choices. In a regime where one’s appearance has quantifiable economic, social, or employment consequences, the freedom to choose is softened by incentives.

As Jerold Abrams warned, “elimination of difference in favor of universality” is a danger: the subversive potential of aesthetic divergence might vanish if everyone gravitates to one “optimal” form. In that world, external difference is suppressed not by coercion but by convergence.

In Foucauldian terms, the internal gaze becomes hyper-charged: we watch ourselves not just in relation to normative bodies, but mediated through technological comparison and feedback. Thus aesthetic consent may be manufactured, not freely chosen.

Part III: Futures, Risks, and Aesthetic Politics

Risk: Aesthetic Stratification

One possible outcome is aesthetic stratification. Access to superior enhancements may create classes of “beautiful bodies” and “unenhanced bodies.” Those who can afford aesthetic augmentation may claim a premium in attractiveness, social capital, or even civic status. Those who decline or cannot afford may be further marginalized.

Aesthetic capital may become a new vector of inequality, alongside wealth and knowledge. In this regard, morphological freedom risks entrenching new aesthetic divides.

Risk: The Tyranny of Beauty

One danger is aesthetic coercion. If enhancement technologies allow one to “optimize” appearance, then those who decline may be stigmatized. Just as cosmetic surgery today carries value or stigma, tomorrow’s enhancements could sharply divide the aesthetic haves and have-nots. The risk is that the aesthetic ideal becomes a form of soft control, a tyranny aesthetic rather than juridical.

In some literatures, this is described as a biopolitical aesthetic regime: bodies become managed, commodified, and judged in terms of their aesthetic performance. The medically commodified body becomes a visible instantiation of social hierarchies — race, ability, gender, class.

Enhancement could thus produce a new aesthetic stratification: the “beautiful body” becomes a code signifying fitness, social capital, moral worth — disadvantaging bodies that resist or fail to conform.

Risk: Loss of Subversive Aesthetic Potential

In the classical cultural critique, subcultures leverage aesthetic difference to resist mainstream norms. Punk, goth, drag, body mods, performance art — these are aesthetic strategies of resistance. If morphological freedom consolidates normative forms, those gestures may lose potency.

In effect, morphological freedom might shift the locus of resistance inward: what remains to subvert once everyone becomes a biotechnological stylization? The capacity to dissent in form may shrink.

Aesthetic Futures of Divergence

Optimistically, morphological freedom could open aesthetic pluralism: fluid, hybrid, shifting bodies, ephemeral morphologies that resist fixity. Bodies could oscillate between forms, adopt multiple styles, or embody motionless paradoxes.

Some speculative artists already work in that vein — “bioart” or “speculative morphology” imagines bodies beyond human typologies. The concept of bioism (aesthetic systems creating novel biological forms) is one example: an aesthetic philosophy of mutation and morphogenesis.

These futures demand both technological possibility and political design. Without intentional scaffolding, the default may be convergence, not diversity.

Toward an Aesthetic Politics of Enhancement

To counter aesthetic tyranny and steward morphological freedom towards pluralism, I propose some guiding principles:

- Aesthetic pluralism as policy goal

Enhancement regimes (structural, regulatory, institutional) should aim to support multiple aesthetic trajectories—not just one “optimal” form or metric. - Protecting the right to abstain

Individuals who decline enhancement should not be marginalized; non-enhanced bodies must remain legitimate aesthetic participants. - Transparency in algorithmic aesthetics

If enhancements are guided by machine models, those models must be audited, de-biased, and contestable. - Cultural institutions for aesthetic critique

Just as art criticism, counterculture, design critique are vital, so should be institutions that challenge and expand morphological aesthetics. - Democratic participation in aesthetic futures

The public should have voice in what kinds of forms, textures, and bodies are normalized or subsidized. - Valuing imperfection and surprise

Some philosophical critiques (e.g. those drawing on Kant or Romantic aesthetics) argue that finitude, fragility, and irregularity are sources of meaning and beauty. Radical perfection might erase those tensions.

(A note: Mark Bailey’s aesthetic argument for a “weak transhumanism” defends precisely that: that human imperfection is an aesthetic and ethical value, not a flaw to be removed.

By situating morphological freedom within the domain of cultural aesthetics, we see that bodies are not just functional nodes but symbolic texts — always already inscribed with power, norms, value, and vision. The press (via Wired, Time, etc.) already reveals how algorithmic aesthetics, beauty economics, and media shape the aesthetic field. Morphological freedom risks saturating that field with new norms.

The aesthetic dimension must be foregrounded in critiques and governance of transhumanist futures. If aesthetics is where difference, identity, and subversion live, then without attention to it, morphological freedom may simply reproduce old hierarchies in new flesh.